DHS postpones threats of REAL-ID Act enforcement

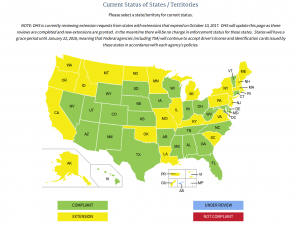

Again postponing its threats to interfere with air travel by residents of “noncompliant” states, the Department of Homeland Security announced today that it has given the last three remaining states either certifications of “compliance” with the REAL-ID Act of 2005, or extensions of time to comply until at least October 10, 2018.

Travelers in all 50 states can continue to ignore the false signs at airports, the false claims being made by state authorities collaborating with the Feds in the national ID scheme, and the blizzard of confused and error-filled news stories (largely based on unverified and misleading DHS and state government press releases) claiming that U.S. citizens will need to obtain, carry, or show passports or other government-issued ID in order to travel by air.

This does not mean that all or most states have actually complied with the REAL-ID Act or are planning to do so. At most 14 states are arguably compliant with the Federal law.

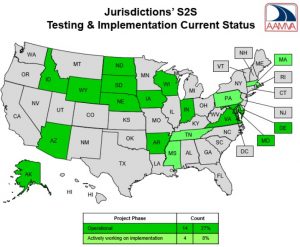

The plain language of the Federal law requires that, “To meet the requirements of this section, a State shall … Provide electronic access to all other States to information contained in the motor vehicle database of the State.” Only 14 states are participating in the outsourced SPEXS national ID database set up to enable this nationwide data access:

In addition to the 14 current SPEXS particpants, the contractor managing the national ID database optimistically lists 4 other states as “actively working on implementation.” But none of these states are listed as having signed letters of intent to join the SPEXS national ID database.

The other 32 states are not compliant with the data-sharing provision of the REAL-ID Act, and have given no indication of intent to comply.

What will happen next?