[Jenoptik “Trafficatch” wireless detection device and the data it collects ]

In the latest escalation of surveillance of travelers, data from automated license plate readers (APLRs) is being merged with data from devices that record the unique identifiers of passing WiFi, Bluetooth, and Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) devices, including always-on devices intended for in-vehicle communications, entertainment, and network access.

Most new cars, SUVs, and light trucks have built-in WiFi access points and Bluetooth and/or BLE connectivity. Each of these wireless access points transmits a unique identifier — usually fixed or not readily changeable by the vehicle owner or operator — to enable devices in the vehicle — cellphones, wireless earbuds, etc. — to establish and maintain connections. Each of those devices broadcasts its own unique and often fixed identifier.

Once the unique identifying numbers of the in-vehicle wireless access points are linked to a vehicle and the vehicle’s registration record and owner by matching the time and location of device detection with an ALPR scan of the vehicle’s license plate, they can be used to track those devices and log their movements in a permanent file associated with the registered owner, even when those devices leave the vehicle.

So if you use your Bluetooth or BLE earbuds to listen to music or make a phone call in a car, even as a passenger, police can and possibly will continue to track your earbuds’ movements and associate them with that car.

According to a report by Byron Tau for NOTUS (a new nonprofit newsroom founded and funded by Robert Allbritton, the former publisher of POLITICO), wireless “device detectors” and the back-end systems to link ALPR and wireless device tracking data have been purchased by local police departments in border communities in Texas using grant money from the US Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the state of Texas.

According to responses to requests for information about bids for government contracts from Jenoptik, the supplier of this system of detectors and databases:

Jenoptik’s Trafficatch wireless device detection is a value add addition to its Vector fixed ALPR solution. Trafficatch records wireless device Wifi, Bluetooth, and Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) signal identifiers that come within range of the device to record gathered information coupled with plate recognition in the area. This can provide additional information to investigators trying to locate persons of interest related to recorded

crimes in the area.

This should be illegal without a warrant, but current case law leaves enough uncertainty that police may feel that they can get away with this sort of tracking without a warrant.

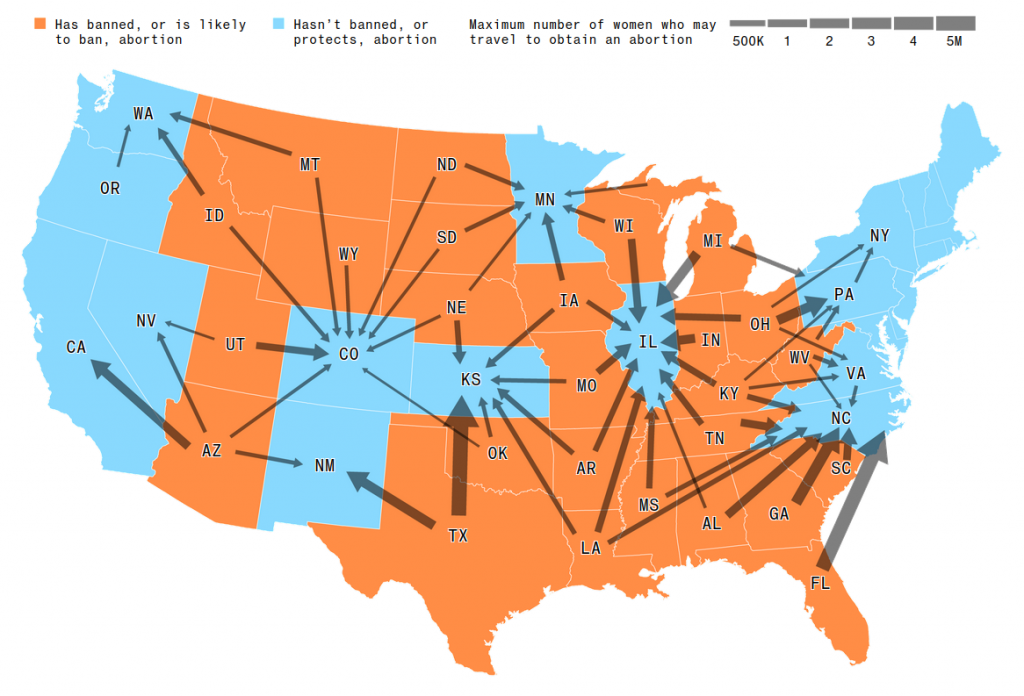

According to the report by NOTUS, this vehicle and device tracking data is being shared through NLETS (the National Law Enforcement Telecommunications Network). The unusual status of NLETS makes it almost impossible to tell how this data is being used. It could be used to track people and vehicles across state lines or other jurisdictional boundaries, including to identify and track people traveling to obtain abortions.

Like AAMVA, NLETS is nominally a nongovernmental nonprofit organizations, but its members are government agencies. AAMVA members are the heads of state driver and motor vehicle licensing agencies; NLETS members are Federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies for which NLETS has long served as a private police network in parallel with public communications networks. Once the operator of a dedicated police telex network (like the parallel special-purpose networks operated for airlines and banks) NLETS is today the hub of the “police Internet“, providing both communications and database hosting services. Because NLETS is nominally “private” and nongovernmental, it itsn’t directly subject to any Federal, state, or local FOIA, public records, or open meeting laws.