A blacklist is not a basis for search or seizure

A lawsuit filed last week in Federal court in Oklahoma City by the Council on American-Islamic Relations on behalf of Oklahoma native Saadiq Long challenges unconstitutional searches and seizures (sometimes at gunpoint) and interference with freedom of movement on city streets and highways on the unlawful basis of a combination of warrantless dragnet surveillance and arbitrary extrajudicial blacklists.

According to Mr. Long’s application for a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction to protect his rights and his life while the case proceeds:

In the span of only two months, Saadiq Long has been repeatedly pulled over, arrested twice, held at gunpoint, and had his car searched by Oklahoma City Police Department officers. It is not because Saadiq is a criminal or suspected of being one. Mr. Long is an American citizen and Air Force veteran who has never been indicted, tried, or convicted of any kind of violent crime.

There is a different reason behind these obvious Fourth Amendment violations. That reason involves the intersection of two different dystopian webs: the vast network of cameras and computers maintained by the Oklahoma City Police Department and a secret, racist list of Muslims that the FBI makes available to Chief Wade Gourley and his officers.

That secret FBI list—variously called the federal terror watchlist, the Terrorism Screening Database (TSDB), and most recently the Terrorist Screening Dataset (TSDS)—is a list of more than a million names, almost all of them Muslim and Arab. The FBI adds whatever names it likes, without meaningful review and in accordance with secret processes and standards, for a stunning array of flimsy reasons. Government suspicion of ongoing criminal activity is not a prerequisite to being listed.

The FBI distributes its list, via the National Crime Information Center (NCIC) Database, to the Oklahoma City Police Department. That is all that the FBI distributes: a list of names. The FBI keeps its reasons and evidence about the placement to itself. Because of this, the Department knows that the FBI put Saadiq Long on a watchlist but the Department has no idea why.

Mr. Long’s mistreatment by the US government — the government of the country where he was born and of which he was and still is a citizen — began when, while serving in the US Air Force from 1987-1998 and living in Turkey, he converted to Islam and applied for discharge from the Air Force as a conscientious objector on the basis of his new beliefs.

The Air Force denied his application for conscientious objector status, gave him an “other than honorable” discharge — and, unbeknownst to Mr. Long at the time, had him put on the US government’s No-Fly List as a “known or suspected terrorist”.

After leaving the Air Force, Mr. Long moved with his family first to Egypt and later to Qatar, where he found work as a teacher of English. He discovered that he was blacklisted by the US government almost a decade later when he tried to come back to the US to visit his terminally ill mother in Oklahoma City.

With assistance from lawyers for CAIR and the CAIR Legal Defense Fund, Mr. Long was eventually allowed to fly to the US to see his mother, but then prevented from boarding any flight from the US to return to his home, wife, child, and job in Qatar. He took a bus from Oklahoma City to Mexico, then a series of connecting flights from Mexico to Qatar via three other countries to avoid overflying US airspace in which the US enforces its No-Fly List even against passengers on flights between other countries.

Mr. Long challenged the denial of his right to travel in Federal court, but the US government kept him on its No-Fly List while the case dragged on. Mr. Long’s current and former names and date of birth were still included on the 2019 version of the No-Fly List that was found on an insecure cloud server last month.

In September 2020, just before the deadline for the government to file briefs with the court in response to Mr. Long’s lawsuit, the government took him off its No-Fly List — a tactic it has often used to evade judicial review of no-fly orders. In June of 2022, the Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit accepted the government’s argument that Mr. Long’s challenge to the no-fly order against him was rendered “moot” by the government taking him off that list, even though he was still on the government’s blacklist (euphemistically and misleadingly referred to as a “watchlist”) as a Known or Suspected Terrorist (KST).

In the meantime, Mr. Long and his family moved back to Oklahoma City, where the local police have acquired and deployed automated license plate readers (ALPRs) to scan vehicles and flag any registered to an owner that matches a listing in NCIC, including the KST list:

Whenever he drives past an ALPR, the system informs police officers that he is on the federal terrorist watchlist and that there is reasonable suspicion to subject him to a traffic stop. As a result, Mr. Long has been subjected to a cascade of traffic stops.

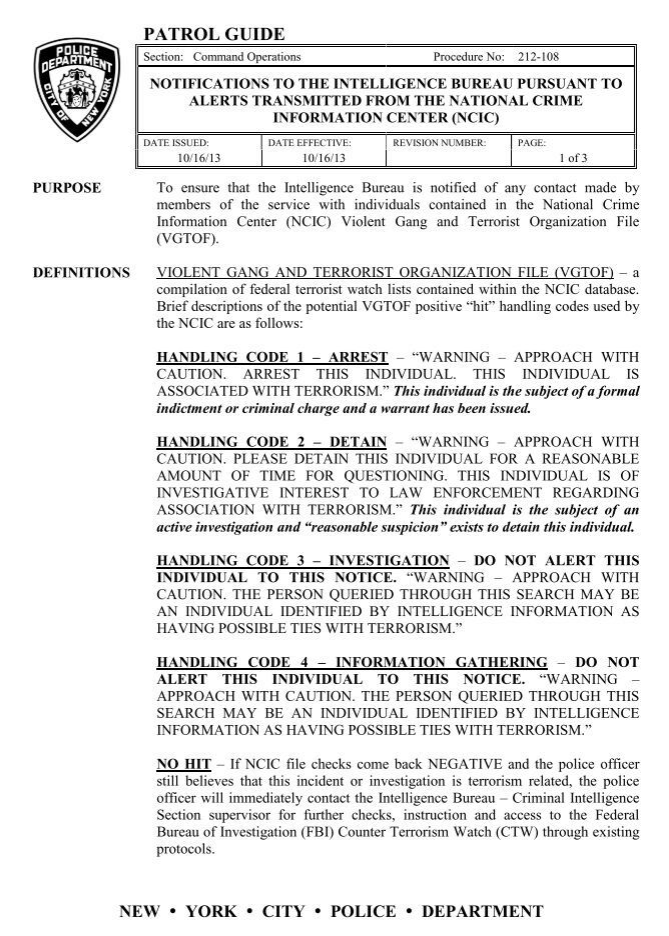

Each entry in NCIC for a “known or suspected terrorist”, and each response to a query to NCIC (including an automated query from an ALPR scan) that matches a KST entry includes a “handling code” that tells police what action the FBI wants them to take.

The New York Police Department summarized an earlier version of handling codes 1-4 for the KST file (under its former name of the VGTOF database) as ARREST, DETAIN, INVESTIGATION (i.e. interrogation), and INFORMATION GATHERING. Only the last of these four handling codes is really consistent with calling this a “watchlist” rather than a “blacklist”.

The New York Police Department summarized an earlier version of handling codes 1-4 for the KST file (under its former name of the VGTOF database) as ARREST, DETAIN, INVESTIGATION (i.e. interrogation), and INFORMATION GATHERING. Only the last of these four handling codes is really consistent with calling this a “watchlist” rather than a “blacklist”.

Some of the KST handling codes indicate dangerousness and are likely to prompt police to carry out traffic stops and searches with guns drawn, as they have done with Mr. Long.

Versions of the KST manual and handling codes released in response to FOIA requests have been redacted. But NCIC is used by, and the documentation is distributed to, thousands of state and local law enforcement agencies, and unredacted versions have been posted online by some of them. The most recent version of the documentation for the KST file that we’ve seen includes five handling codes, but the unlawfulness persists.

The problem with this, and the crux of Mr. Long’s latest complaint, is that the presence of a name on a list — where the entry on the list indicates neither a court order (warrant, injunction, restraining order) nor a determination by anyone that probable cause exists to suspect the person named on the list of a crime — does not constitute a Constitutional basis for arrest, detention, or denial of any other rights. As Mr. Long’s complaint states, “Watchlist status does not create reasonable suspicion of ongoing criminal activity because placement on the watchlist does not require reasonable suspicion of any crime.”

The FBI actually admits this: The NCIC manual for the KST file says that, “No arrest or detention should be made based solely on a KST File record.” Some police departments repeat this boilerplate to their officers. The Honolulu Police Department, for example, has published procedures for encounters with individuals on the KST list which instruct officers: “Do not detain or arrest individual(s) unless there is evidence of a violation of law as the individual cannot be stopped based on the TSC [Terrorist Screening Center, i.e. the KST file] alone.”

But realistically, what are police expected to do when they are alerted that inquiring minds at the FBI’s Terrorist Screening Center want to know about a particular vehicle and who is driving it?

It’s hard to avoid the inference that the goal of this scheme is to prod local police to find or invent excuses for pretextual stops, searches, identification, and interrogation of blacklisted people. What other reason would there be to deploy an elaborate and expensive system to alert police that the FBI wants them to stop, search, identify, and question certain individuals, but that there is no legal basis for the police to do so?

In the case of Mr. Long, the Oklahoma City Police have repeatedly made up lying pretexts to stop and question him and and search him and his vehicle.

Oklahoma City Police have told Mr. Long that they stopped him for a traffic violation — but then told him that the actual reason he was pulled over was that his car was flagged in NCIC as registered to a suspected terrorist. They have told him that they stopped him for a traffic violation that they couldn’t have seen from their location, even if it had occurred. And they have told him that they stopped him because his car had been reported stolen — when he was driving his own car, which neither he nor anyone else had reported stolen.

Within days after Mr. Long’s complaint and Long’s application for a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction were filed, the defendants agreed to stipulate that “The Oklahoma City Police Department acknowledges that neither Saadiq Long nor any other person should be stopped by officers based solely on that individual’s KST File status in the NCIC. And the Chief of Police swore that he had “issued training to all officers… that specifies that neither Saadiq Long nor any person listed on the ‘Terrorist Watch List’ should be stopped based solely on his or her presence on the list.”

That’s a small step in the right direction, but it does nothing about the lies, the pretextual stops, the damage already done to Mr. Long, or all the other law enforcement agencies throughout the US that are undoubtedly responding similarly to blacklist-based alerts.

A valid list of people to be arrested, detained, or prevented from exercising their right to travel — whether that’s a No-Fly List for common-carrier travel or a “no-drive” list for travel on public streets and highways — should be a list derived from court orders, not from extrajudicial agency actions. Secret, arbitrary, and often bigoted government blacklists have a long and unfortunate American history, but they are unconstitutional. Neither government agencies nor common carriers should interfere with travelers’ rights based solely on whether their names appear on these blacklists.

Pingback: Links 05/02/2023: Wayland in Bookworm and xvidtune 1.0.4 | Techrights

Pingback: Lessons from the first “no-fly” trial – Papers, Please!

Pingback: Broader challenge to Federal blacklists filed in Boston – Papers, Please!

Pingback: WATCH: Heavily Armed Police Surround Man Acquitted In Whitmer Kidnapping Case - Walls-Work.org