Countdown to a crackdown on flying without ID

The Department of Homeland Security has added a Countdown to REAL ID Enforcement at airports to its website. But questions remain as to what this really means, despite our best efforts to find out.

What — if anything — will really change at Transportation Security Administration checkpoints when this countdown clock runs out on May 3, 2023?

Nothing in the law will change on that date. The REAL-ID Act of 2005 established criteria for which ID credentials can be “accepted” by Federal government agencies, in circumstances where individuals are required by Federal law or regulations to possess and/or show some evidence of their identity. But the consistent position of the DHS and TSA in litigation has been that no law or regulation requires air travelers to possess or show any ID. And the REAL-ID Act did not create any new requirement to have or show ID to fly.

Since the REAL-ID Act applies only to which IDs are accepted from those who choose to show ID to fly, it should have no effect, now or at at any date in the future, on those who don’t have, or choose not to show, ID to fly. They still have the right to fly without ID — as more than a hundred thousand people do every year — subject at most to a more intrusive administrative search of their person and baggage.

The “deadline” announced by the DHS and TSA might indicate plans for new regulations that would impose a requirement for air travelers to have or to show ID. But no such regulations have been proposed or included in DHS or TSA agendas of planned rulemaking.

Despite the lack of any apparent legal authority, however, it appears from the latest extrajudicial DHS and TSA rulemaking-by-press-release that these agencies plan to begin preventing anyone from flying without ID on or after May 3, 2023, on unknown grounds.

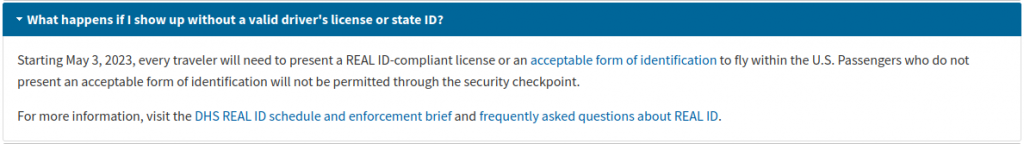

The following statement now appears on the DHS and TSA websites:

What happens if I show up without a valid driver’s license or state ID?

Starting May 3, 2023, every traveler will need to present a REAL ID-compliant license or an acceptable form of identification to fly within the U.S. Passengers who do not present an acceptable form of identification will not be permitted through the security checkpoint.

This would be a major change, with no legal basis, from current practice or any previously disclosed DHS or TSA plans.