Airline passenger data and COVID-19

The New York Times published a lengthy but deeply flawed report last week, “Airlines Refused to Collect Passenger Data That Could Aid Coronavirus Fight.” Here’s the lede:

For 15 years, the U.S. government has been pressing airlines to prepare for a possible pandemic by collecting passengers’ contact information so that public-health authorities could track down people exposed to a contagious virus.

The airlines have repeatedly refused, even this month as the coronavirus proliferated across the United States. Now the country is paying a price.

The implication of both the headline and the article is that airlines “could” have collected and provided the government with the (additional) information it wants. But that isn’t true.

While the Times’ reporters interviewed multiple government sources, they failed to fact-check this allegation with any sources independent of airlines or the government. And they failed to mention — if they even realized, which they may not have — that this isn’t an isolated dispute, but part of a continuing saga that has been going on since 9/11.

The supposed basis for the government’s demands for airlines to collect and pass on more information about travelers has shifted from “security” to “health.” But what’s happening is just another chapter in a long-running story.

Understanding that story requires a deep dive into twenty years of history of airline and government collaboration and conflict over collection and use of data about travelers.

Here’s some of the factual and historical context that the Times overlooked:

Collaboration by airlines with government surveillance of travelers is nothing new. Under the “third party doctrine” in U.S. law, airline reservations have been, and still are, considered to belong to the airlines, not to the passengers to whom they pertain.

Airlines could, and routinely did, “voluntarily” share any or all of this data with police and other government agencies, even before 9/11, as they admit in their latest submission to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC):

In 2001, Congress passed the Aviation and Transportation Security Act (“ATSA”), which responded to aviation security issues identified after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks and required airlines to provide to the U.S. government information or access to information regarding passengers and crewmembers. Specifically, Congress required that airlines make PNR [Passenger Name Record] data available to the Customs Service (“Customs”) upon request.

Notably, even before this mandate, airlines voluntarily provided the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (“INS”) and Customs access to reservations systems for the purpose of sharing PNR data. Accordingly, the U.S. government, through CBP, which replaced INS and Customs, has long had access to PNR.

What changed after 9/11 is that the U.S. government (followed by other governments) not only wanted real-time root access to airlines’ reservation systems — which was quickly provided — but wanted airlines to collect additional data airlines didn’t routinely collect and had no authority to demand from passengers, and to structure this data for government use in ways for which there were, as of 9/11, no industry standards. This required changes to the most basic industry-standard protocols for data transmission (starting with the AIRIMP), new database fields and formats, and then changes to every layer of interface and every system that stores, processes, or transmits passenger data.

Before 9/11, aviation security was under the jurisdiction of the Federal Aviation Administration. The FAA was a typical revolving-door regulatory agency — which meant, on the positive side of the ledger, that it had a deep understanding of airline operations.

After 9/11, however, anyone in government who had any actual experience with airline operations or security was treated as a failure tainted by 9/11, and pushed out of newly ascendant “homeland security” roles in favor of newcomers to aviation with backgrounds at the NSA and other such agencies.

These newcomers didn’t realize the extent to which airline IT was its own sophisticated parallel universe with its own standards and norms. They assumed that they knew much more about airline IT than they did. They were genuinely shocked when they revealed their proposals for passenger data collection and sharing to the airline industry, expecting eager cooperation, and were told that what they were proposing would cost a billion dollars and take a decade to implement.

Airlines were never opposed to passenger surveillance or to collaboration with police, and tried to make this clear to the DHS. We’re happy to help, they said, as long as the government reimburses us for the cost of collecting data for government purposes, and as long as we get a free ride to keep that data and use it for our own purposes.

The DHS got its way, but it couldn’t work magic. Airlines implemented the changes the DHS wanted, at a cost the DHS eventually estimated in its official regulatory assessments at more than $2 billion in unfunded mandates. It took about a decade for the changes to data schemas and protocols to percolate up to all of the end user interfaces and procedures for passenger data processing. The air travel industry had to absorb all of these costs.

Airlines also got something out of the deal, though. No restrictions whatsoever were placed on their ability to retain, use, or transfer to third parties any or all of the data that passengers are required by government order to disclose to airlines.

(The same issues have arisen again with respect to biometric data, as government agencies outsource to airlines, airport operators, and other contractors the collection of facial images used by the government to track travelers, but also made available for free use by airlines and airports for their own purposes. This outsourcing of government surveillance has become central to the debate about airport use of biometrics.)

Allowing airlines to keep and use data collected pursuant to government mandates was a cheap and convenient way for the DHS and other government agencies to appease the airlines. Giving airiness the use of this data didn’t cost the government anything. And the government’s “see no evil, hear no evil” approach to letting airlines retain and use this data allowed the government to avoid responsibility for oversight over the pervasive, preexisting, and continuing violations of data protection norms by the airline industry.

But that wasn’t the end of the story. Government agencies kept coming up with new, different, and overlapping demands for data about travelers, in different formats. Airlines lobbied ICAO to adopt a PNRGOV standard format and protocol for pushing mirror copies of entire airline reservations to all governments worldwide, but that wasn’t enough for some governments.

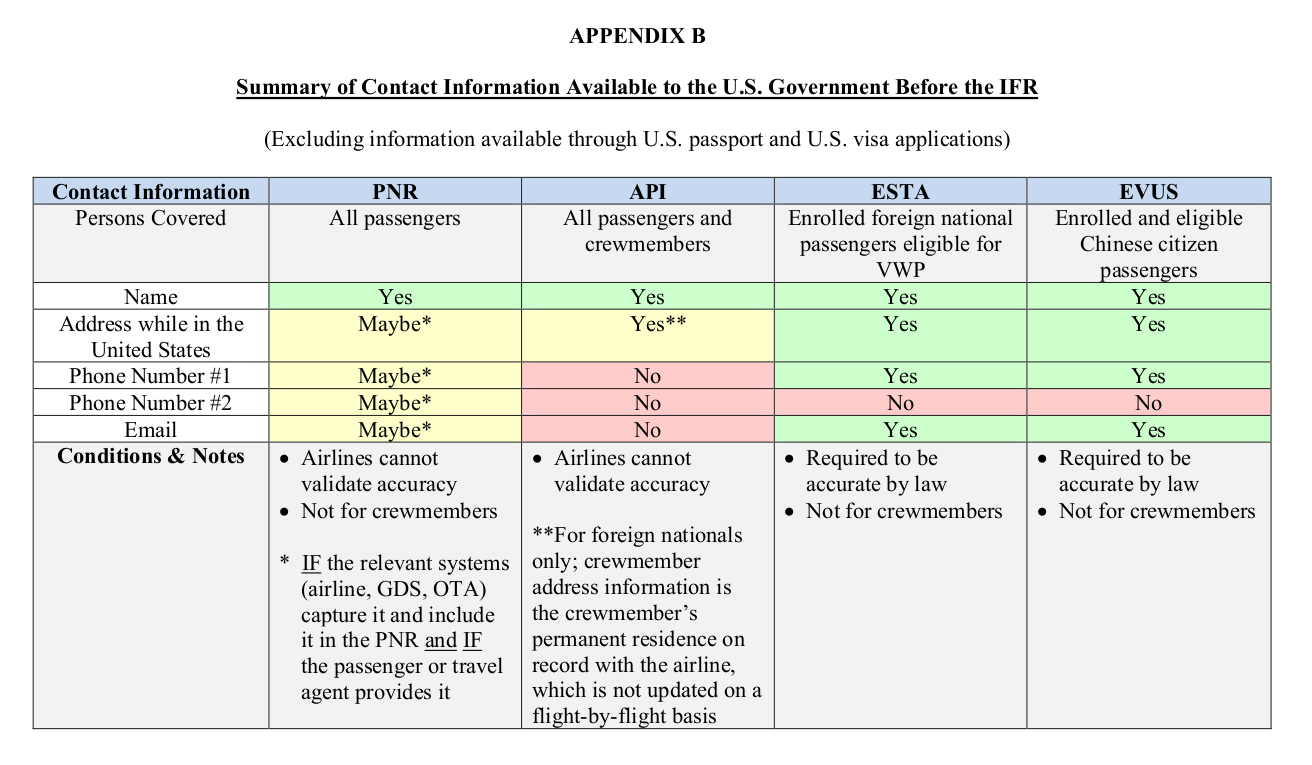

[Some of the partially overlapping and differently formatted datasets of information about international travelers already collected before the latest CDC Interim Final Rule (IFR), as outlined by airlines in their comments to the CDC.]

[Some of the partially overlapping and differently formatted datasets of information about international travelers already collected before the latest CDC Interim Final Rule (IFR), as outlined by airlines in their comments to the CDC.]

It was in this context — a context entirely overlooked by the Times in its latest story — that the CDC came along a few years after 9/11, asking airlines to collect yet another set of data about each passenger (including some data elements that the DHS had specifically asked for before, but had realized weren’t available), in yet another format.

The CDC proposal for mandatory collection by airlines of additional passenger tracking information was first published for comment in 2005, but not finalized until after a second round of comment on a revised proposal in 2016. Last week’s New York Times article reports on some of the objections made by airlines, but doesn’t mentions the objections to both the 2005 and in 2016 proposals by privacy, civil liberties, and human rights groups. Some of these objections were related to the lack of due process in the quarantine rules, but others, including those by the Identity Project, also related to the data collection mandate. As we argued:

CDC has the statutory authority to “examine” individuals at an infectious disease checkpoint, if there is a basis for a reasonable belief that they are infected with a communicable disease. But they have the right to remain silent, and must be allowed to proceed without more than a brief delay unless some evidence other than their silence provides probable cause for belief that they are infected with a communicable disease.

The regulations promulgated by the CDC in January 2017 required airlines to provide the CDC with additional information about passengers (beyond that already required to be collected and provided to the DHS), only “to the extent that such data are already available and maintained by the airline.” The CDC statement accompanying the 2017 final rule said that:

HHS/CDC intends to synthesize, analyze, and report within the next two years on strategies to reduce duplication of the collection of passenger/crew manifest information in coordination with DHS/ CBP. The report will include any recommendations (e.g., IT systems improvements to facilitate enhanced search capabilities of passenger data, increased efficiency to relay passenger data, improvements to the existing CDC–CBP MOU) to ensure that the collection of passenger or crew manifest information do not unduly burden airlines, vessels, and other affected entities. HHS/CDC intends to seek public comment on the report and any recommendations regarding the costs and benefits of activities implemented in 42 CFR parts 71.4 and 71.5. Estimates of both costs and benefits in the NPRM [Notice of Proposed Rulemaking] regulatory impact analysis were not very large because HHS/CDC is not implementing a new data collection requirement.

So far as we can tell, neither the CDC nor DHS ever published or sought comment on such a report. Instead, CDC promulgated a new “Interim Final Rule” rule in February 2020, on an emergency basis without notice or comment, predicated on assumptions about airline IT systems and capabilities that airlines had already told the CDC were incorrect.

Since the promulgation of the CDC Interim Final Rule, airlines have filed voluminous objections to its legality and to the feasibility of compliance. Most interesting are those of Airlines For America (US-based airlines), IATA (airlines worldwide), and trade associations of regional and charter airlines.

The airlines’ joint comments omit, naturally, any mention of the fact that airlines are being allowed to retain and use the data they collected on behalf of the CDC. And they are grossly hypocritical in pointing to possible incompatibility of the CDC rules with US and foreign privacy laws that these airlines have never complied with. But the A4A/IATA submissions to the CDC provide an extremely useful overview of the passenger data ecosystem and the standards and rules that have developed for sharing information about air travelers with government agencies, not just with respect to the CDC but in general:

- Joint comments of A4A, IATA, et al.

- Attachments to airline joint comments, Part 1

- Attachments to airline joint comments, Part 2

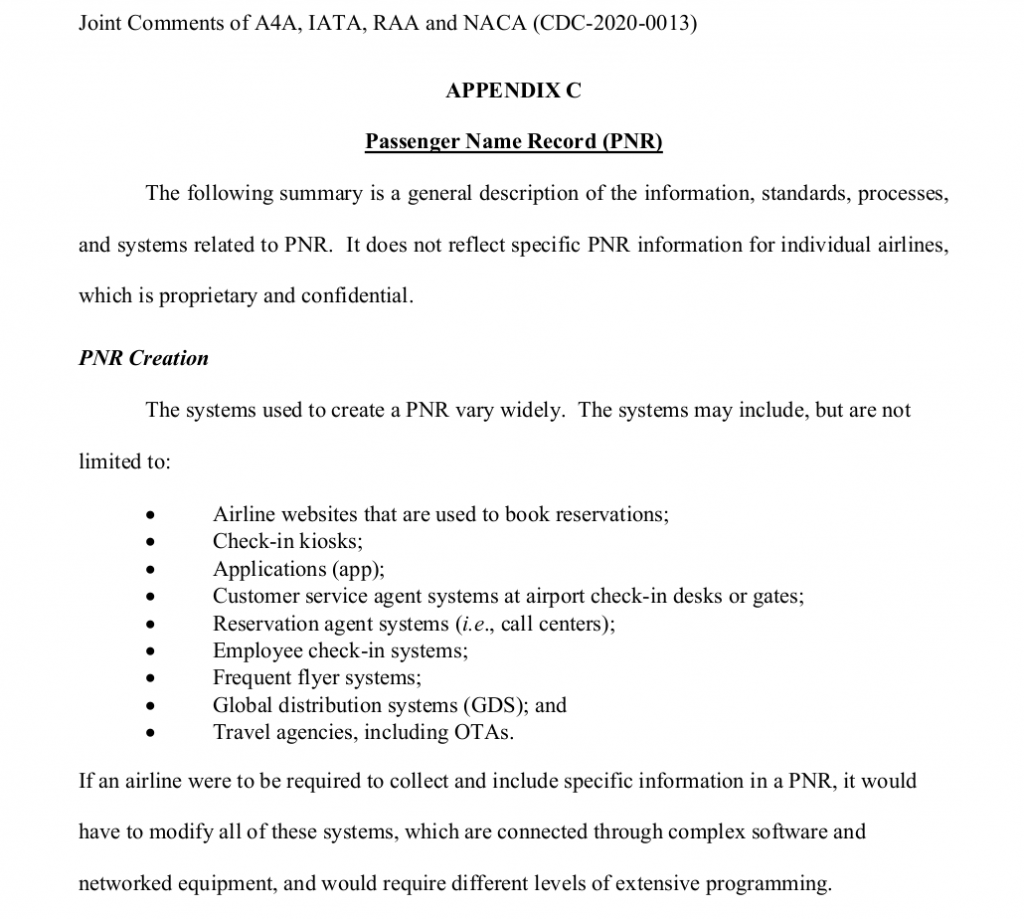

[Some of the systems that would need to be modified to collect and deliver the additional data demanded by the CDC.]

[Some of the systems that would need to be modified to collect and deliver the additional data demanded by the CDC.]

The CDC presumes that airlines have infrastructure, in the form of IT systems that are interconnected between industry stakeholders, that simply does not exist. Like a COVID-19 vaccine, the creation and modification of industry-wide systems to meet the IFR requirements will take substantial time to develop, must conform to international standards and coordinated across every stakeholder, and cannot be willed into existence by regulatory requirements….

On a global scale with 222 airlines flying internationally to and from the United States, travel agents worldwide, and other third parties, the entire airline industry simply cannot modify its operations, systems, and processes, in less than 12 months, to collect and provide passenger contact information through existing airline data channels to the CDC. The constellation of systems designed in accordance with international standards, processes, and operations by scheduled passenger airlines are extraordinarily complex, and charter airlines face additional challenges because we have less interaction with passengers and their systems and operations are fundamentally different from those of scheduled passenger airlines….

We conservatively estimate that scheduled passenger airlines need at least 12 months to ensure that all relevant systems (i.e., reservation systems, kiosks, websites, mobile applications, etc.) are modified to capture and include specific passenger contact information in every PNR….

We conservatively estimate that the costs to modify systems for most passenger airlines will be considerably more than $1 million per airline and the total impact across airlines will far exceed $164 million (based on $1 million for each of the 183 airlines carrying passengers to the United States). The actual costs will be enormous — one airline estimates that the costs to modify its systems will be approximately $23-46 million. Moreover, the collective costs to modify systems across the entire airline industry, including airlines, travel agents/OTAs, and GDSs, will be even greater….

In practice… many airlines do collect some passenger contact information that the CDC requires in the IFR. Airlines generally collect and include the passenger’s name in the PNR.

However, no airline or third-party system is designed to ensure the capture and transmission of [all of] the passenger contact information that the IFR requires via PNR. Even if an airline collects more contact information than the passenger’s name, its systems may not be designed to include such information in the PNR, in part because it is not required to do so and to comply with privacy laws. As the CDC is aware, some airlines’ systems do include address, phone number, and email address in the PNR. However, a PNR with multiple passengers may contain a single address, phone number, and email address, which may belong to one of the passengers or… to a travel agency.

In their comments, the airlines also note that the CDC rules require airlines to provide the requested data “in a format acceptable to the Director” of the CDC. It’s not clear when or how the acceptable formats will be spelled out, or — given the real practical problems pointed out by the airlines — how soon, or at what point in the ticketing and travel process, passengers will start being asked for the additional information demanded by the CDC.

The airlines argue strenuously, and undoubtedly correctly, that the CDC must know that the new rules can’t possibly be implemented by airlines in less than 12-18 months, by which time the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to have ended or substantially abated. This isn’t a rule to cope with the current crisis. Rather, it is an attempt to exploit the coronavirus crisis to adopt a rule that will be implemented only afterward and remain in effect indefinitely:

The IFR … needlessly extends far beyond COVID-19, which is a novel virus posing near-term challenges…. The CDC should create broad long-term rules through a full Administrative Procedure Act (“APA”) rulemaking process. The CDC’s claim that COVID-19 justifies the IFR is a pretext to avoid this process….

Moreover, by the time airlines, travel agents/OTAs, GDSs, and CBP are able to develop and implement the system modifications the IFR will require—which, for the reasons explained above, will undoubtedly take at least a year—it is doubtful the IFR will serve any effective purpose as it relates to COVID-19. The U.S. government has essentially acknowledged this shortcoming to airlines, while admitting that it still wants such information. The IFR is also not “interim”: it amends the CFR [Code of Federal Regulations] and nothing in its language suggests it will have a short shelf-life. Although the preamble states that the rule will expire when COVID-19 ceases spreading or CDC determines it is no longer needed, the rule itself contains no sunset provision. The preamble, the text of the IFR, and CDC’s statements to airlines contemplate that the rule will become a permanent fixture within the CFR.

To be clear, airlines have been asserting their own interests, not those of their customers. Airlines, unlike travelers, have legal standing to challenge government demands for information about passengers. No far as we can tell, no airline has ever done so, in any US or foreign jurisdiction.

The current crisis is also a reminder of the inherent unreliability of policies that purport to limit how information will be used. If data is later perceived to be “needed” for other purposes, it will be used, regardless of the policies that supposedly applied when it was collected. Germany, for example, has enacted legislation (of as yet untested compatibility with German and European basic law and rights) to allow passenger data originally collected and provided to the Federal police for enforcement of criminal laws to also now be shared with health agencies and used to enforce quarantine orders.

If AirLines want their Bailout Money; they will put their Ducks in a row and LockStep (GooseStep), with Government Orders.

Now is the Time afters many steps and much planning for the stageing of the Global TakeOver.

WE ARE IN IT NOW…..SO WAKE UP AND GET REAL.

Surveillance during COVID-19: Five ways government and companies are using the health crisis to expand surveillance (Just Futures Law, April 9, 2020):

https://justfutureslaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/COVID.SURVEILLANCE.JFLv4_.pdf

Pingback: COVID-19 & Digital Rights: Document Pool - EDRi

“Airlines: Industry Ill-Equipped To Collect More Traveler Data For Contact Tracing” (Jay Boehmer, The Beat, May 28, 2020):

https://www.thebeat.travel/News/Industry-Ill-Equipped-To-Collect-More-Traveler-Data-For-Contact-Tracing

“LETTER: Hasbrouck On CDC Data-Collection Rules” (The Beat, May 29, 2020):

https://www.thebeat.travel/Views/Hasbrouck-On-CDC-Data-Collection-Rules/28336

Pingback: “Put them on the no-fly list!” – Papers, Please!

Pingback: “Put them on the no-fly list!” – The Mad Truther