Canada copies US “Secure Flight” air travel controls

While we were watching US election returns, our neighbors to the north were adopting new travel regulations that incorporate some of the worst aspects of the US system of surveillance and control of air travel, and in some respects go even further in the wrong direction.

Canadian authorities don’t generally want to be seen as imitating the US or capitulating to US pressure. There was no mention in the official analysis of the latest amendments to the Canadian regulations of the US models on which they are based. But according to the press release this week from Public Safety Canada, the latest version of the Canadian Secure Air Travel Regulations which came into force this week for domestic flights within Canada as well as international flights to or from Canada include the following elements, each of which appears to be based on the US Secure Flight system:

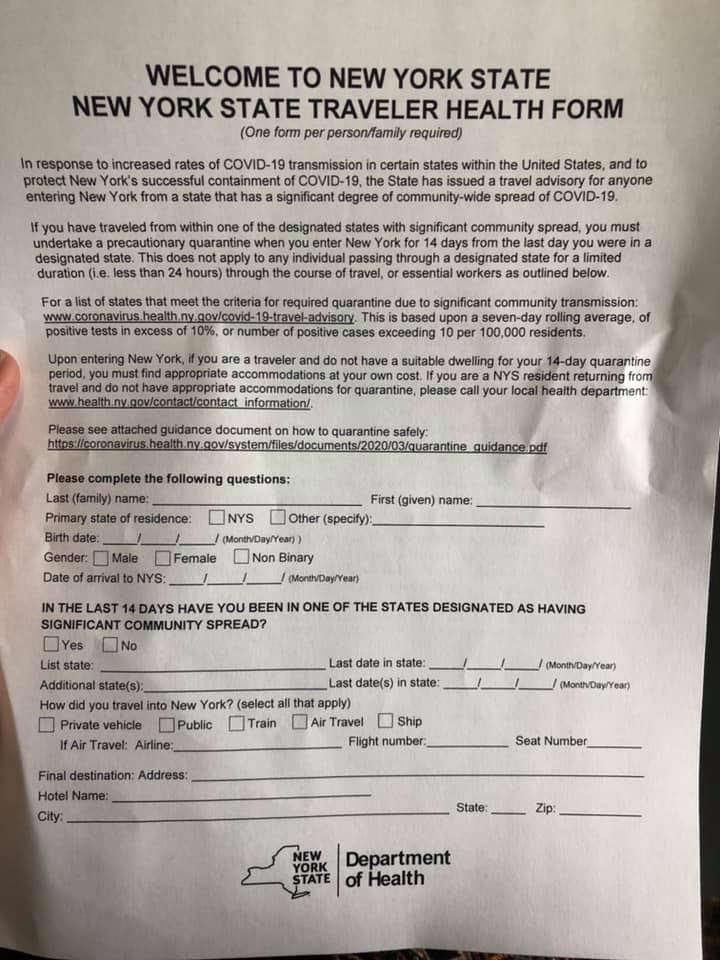

- All air travelers will be required to show government-issued photo ID. The Canadian ID requirement to fly is now explicit, unlike the de facto ID requirement that the US Department of Homeland Security is attempting to impose and already wrongly enforcing, in some cases, without statutory or regulatory authority. The Canadian rules appear to reflect the authority to deny passage to air travelers without ID that the DHS has sought, but has not yet been granted, in the US.

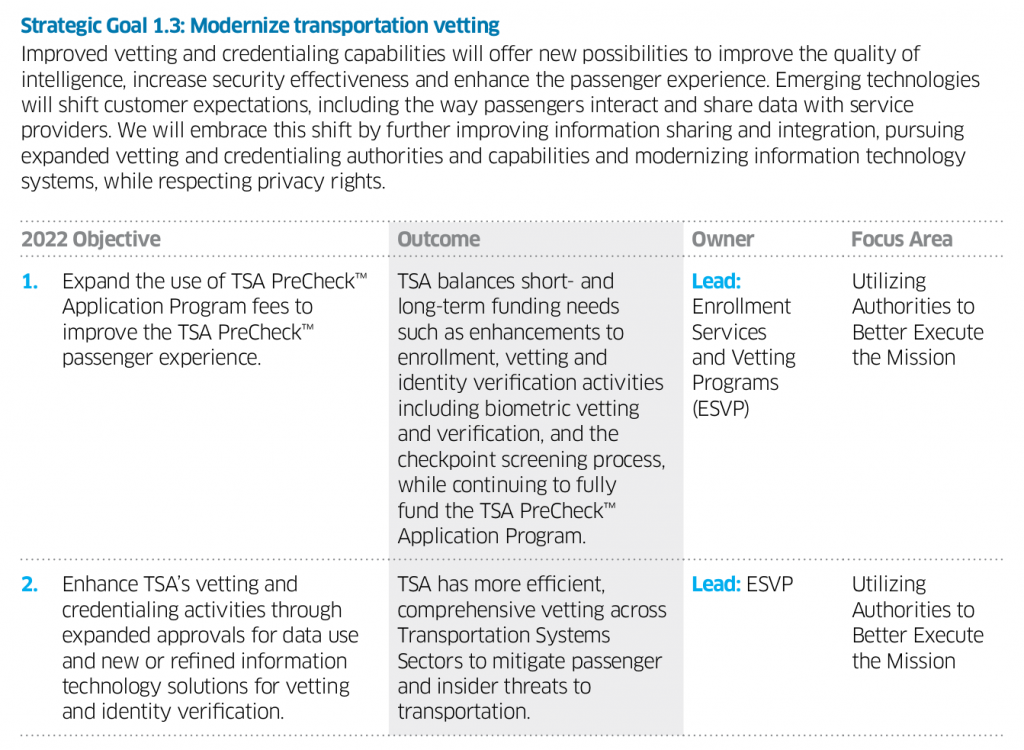

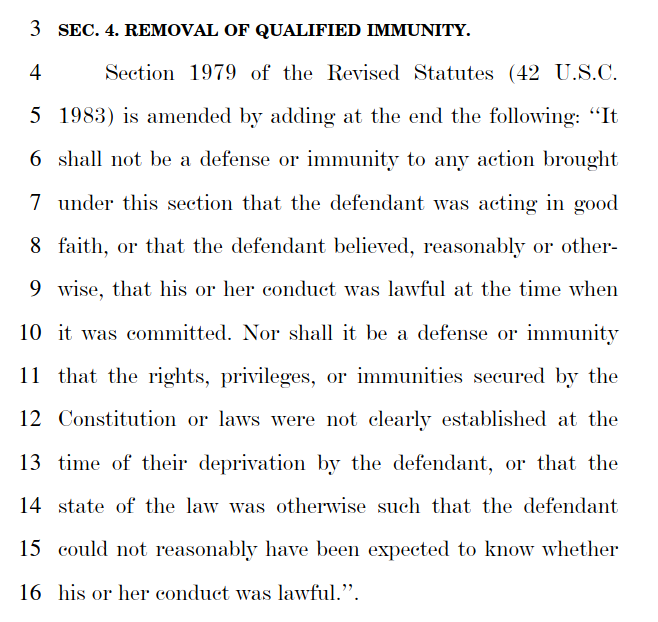

- Fly/no-fly decision-making will be transferred from airlines (making binary fly/no-fly decisions on the basis of a no-fly list provided by the government) to a government agency. After receiving information about each passenger from the airline, Public Safety Canada will transmit a permission messages to the airline with respect to each would-be passenger on each flight, with a default of “not permitted to board” if no message is received by the airline from the government. Exactly this change was made in the US through the Secure Flight regulations promulgated in 2008. This change serves two purposes for the government: (A) it provides a basis for building positive real-time government control over boarding pass issuance into airline IT infrastructure, converting every airline check-in kiosk or boarding-pass app into a virtual government checkpoint that can be used to control movement on any basis and for any reason that the government later chooses, and (B) it enables the switch from blacklist-based no-fly decision-making to more complex and opaque real-time algorithmic pre-crime profiling based on a larger number of factors.

- Air travelers in Canada will be required to provide the airline with their full name, gender, and date of birth, as listed on government-issued ID, and airlines will be required to enter this data in each reservation and transmit it to the government 72 hours before the flight or as soon as the reservation is made, whichever comes first. All of this is exactly as has bene required for flights within the US since the coming into force of the DHS Secure Flight regulations. This additional information about each passenger enables the government to match passengers’ identities, in advance, to other commercial and government databases, and thus to incorporate a much wider range of surveillance and data mining into its profiling algorithms.

- Travelers will be able to apply to the government for a “Canadian Travel Number” which, if issued, they can enter in their reservations to distinguish themselves as whitelisted people from blacklisted people with similar names and/or other similar personal data. This Canadian Travel Number is obviously modeled on the “redress number” incorporated in the US Secure Flight system. The goal of this “whitelist number” is to reduce the complaints and political embarrassment of the recurring incidents of innocent people with similar names, including children, being mistakenly identified as blacklisted people, and denied boarding on Canadian flights. The problem, of course, is that this does nothing to help the innocent people who are correctly identified as having been blacklisted by the government, but who were wrongly blacklisted in the first place.

As our Canadian friends at the International Civil Liberities Monitoring Group put it in a statement this week:

These regulations do not address the central, foundational problems that plague Canada’s No Fly List system and will continue to result in the undermining of individuals’ rights as they travel….

The Canadian government had a solution from the beginning, and they still do: abolish the No Fly List. If someone is a threat to airline travel or to those in the region they are traveling to, charge them under the criminal code and take them to court where they can defend themselves, in public.

It’s time to be done with secret security lists once and for all.