Oral arguments have been scheduled by two different Federal District Court judges for this Thursday, July 2, 2020, on motions for temporary restraining orders against enforcement of separate state health orders mandating 14-day quarantine of all people arriving in New York or Hawaii from out of state.

Corbett v. Cuomo will be argued at 2 p.m. EDT by telephone in New York; Carmichael v. Ige will be argued in person (and not available for remote auditing) at 11 a.m. HST in Hawaii.

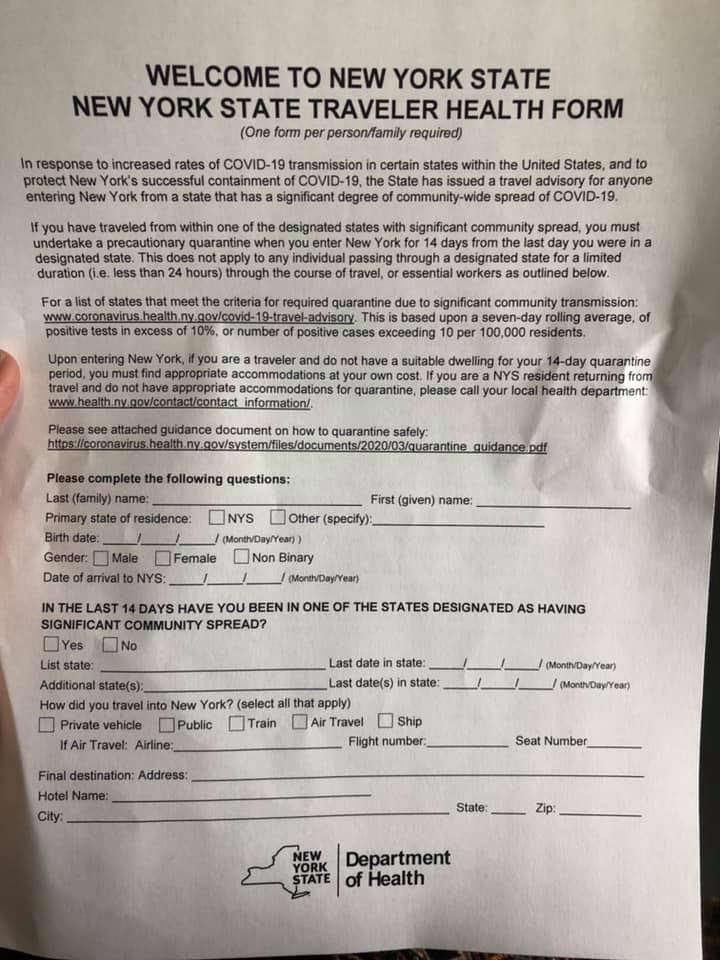

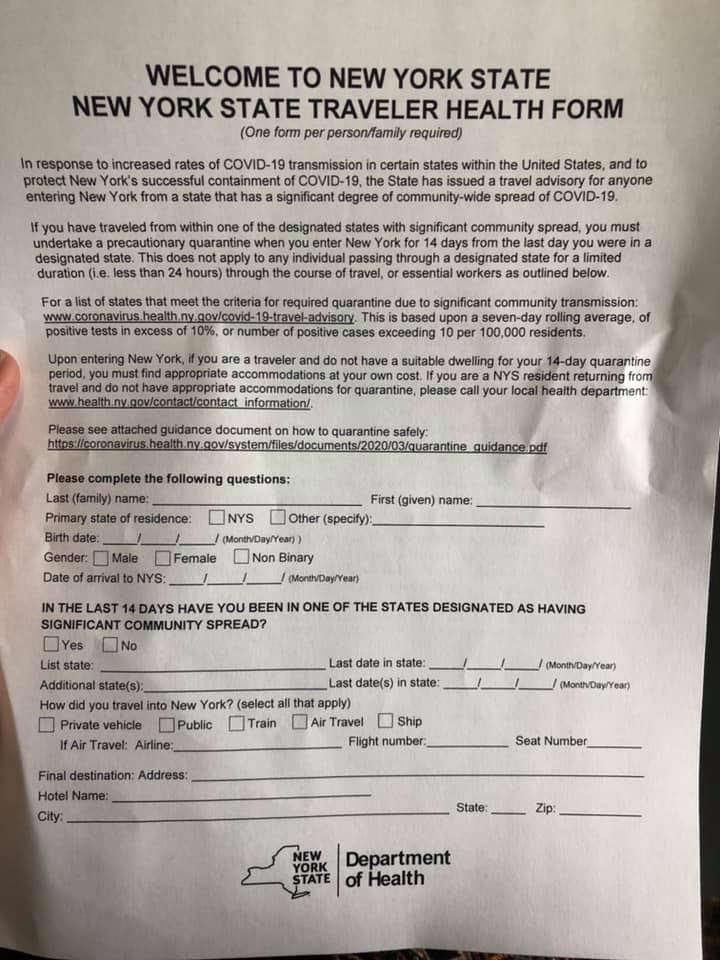

The Hawaii quarantine order, as we’ve discussed previously, applies to anyone arriving from out of state. The New York order only applies to people who have visited certain states designated by New York authorities, but those states include almost half the US population. The blacklisted states include Georgia and Texas, so anyone who changes planes in Atlanta, Houston, or Dallas-Ft. Worth — all major airline hubs — en route to New York is affected, even if they are coming from some other, less-infected state.

As the complaint in the New York case notes, it’s unclear whether those involuntarily quarantined in New York will be held in jails, hospitals, or some other locations, but according to a public statements by New York Governor Cuomo cited in the complaint, they are to be detained at their own expense.

On its face, the New York order applies to anyone arriving in New York who has recently been in any of the blacklisted states, even if they don’t intend to stay in New York. This would include people changing planes in New York, or passing through on the short New York section of Interstate 95 or on the Northeast Corridor between New England and New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and points south and west. All routes between New England and the rest of the US pass through either New York or Canada. With the US-Canada border mostly closed, enforcement of the New York travel restrictions would render New England an isolted island accessible only by air.

In addition to the 14-day quarantine, New York state has also begun demanding that each interstate traveler arriving by air (regardless of their state of residence or whether they have visited any of the blacklisted states) complete and sign a written declaration (Exhibit B to the complaint) about themselves, their business affairs, and their travels.

The Hawaii and New York quarantines and the New York questionnaire for interstate air travelers are all backed with threats of arrest and fines for noncompliance.

The New York quarantine order and travel declaration are being challenged by Jonathan Corbett, who has his primary residence and business interests in Brooklyn, New York, but is also a member of the California bar who practices law in California. Before his admission to the bar, Mr. Corbett had brought multiple pro se lawsuits challenging restrictions on air travel and searches of travelers, including the TSA’s use of “virtual strip-search” imaging machines.

Significantly, in light of the written declaration that the state of New York is now ordering arriving air travelers to fill out and sign, Mr. Corbett has also previously challenged administrative interrogations of air travelers (who aren’t suspected of any crime) by, or at the behest of, the TSA. That case was dismissed without the court reaching the Constitutionality of administrative interrogation of travelers. So far as we know, Corbett v. Cuomo is the first time this issue has arisen in a COVID-19 quarantine case.

There’s extensive case law on administrative searches, but very little on administrative interrogations. Mr. Corbett argues, and we concur, that he has an absolute right to stand mute in response to interrogatories by state authorities at state borders or airports.

In the current circumstances, it’s tempting to give health authorities a free pass for whatever they do, “because pandemic”. But that would be a mistake. We’ve already seen what happened when authorities were given free rein to impose new restrictions on travelers after September 11, 2001, “because terrorism”. Many of those measures had no rational relationship to the prevention of terrorism, were implemented without regard for Constitutional rights, and have become permanent, or effectively so.

How long will the current health emergency last? And will Federal, state, and local government agencies return to their prior practices at airports and borders if and when the emergency is declared to have ended, or will restrictions imposed during the pandemic become the permanent “new normal”?

If our Constitution is to have meaning, and if there is a sufficient justification for restrictions on travel, it should be possible to defend those restrictions on the basis of the Constitution. It should not be necessary to argue for suspending the Constitution.

Read More →

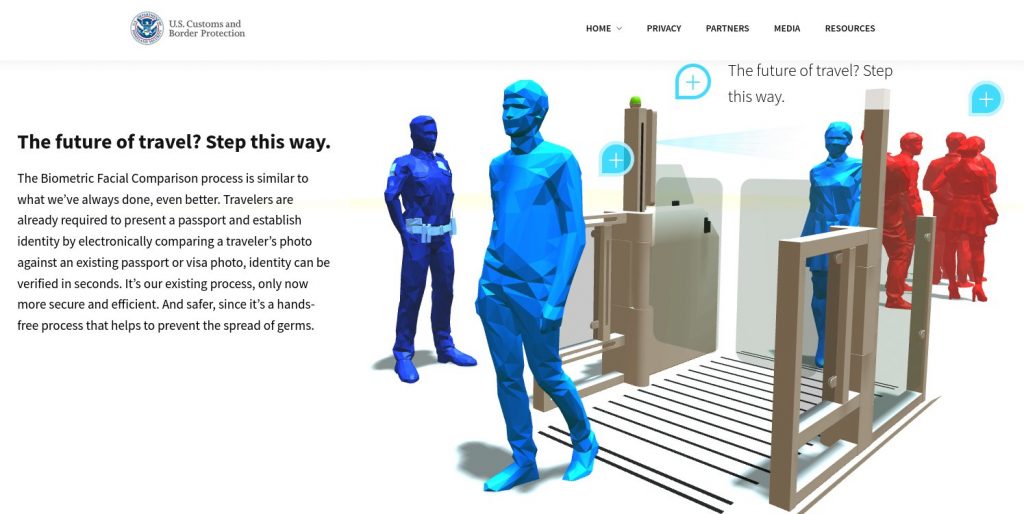

[Illustration from CBP website. The claim that facial recognition “helps to prevent the spread of germs” is especially bogus, since facial recognition requires travelers to remove their face masks wherever it is used.]

[Illustration from CBP website. The claim that facial recognition “helps to prevent the spread of germs” is especially bogus, since facial recognition requires travelers to remove their face masks wherever it is used.]