TSA Confirm.ID: TSA plans to charge air travelers without ID or without REAL-ID $3B a year in extra fees for extra questioning

Since scare tactics haven’t gotten everyone in the U.S. to sign up for REAL-ID or show ID whenever they fly, the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) is turning to extortion through the threat of a new $45 fee to fly without “acceptable” ID.

The proposed fee and the modified “ID verification” program it would pay for are being described by the TSA as a fait accompli. But even if they were authorized by Congress and Constitutional — which we don’t think they are — they have several months-long procedural hurdles to clear before they could legally be put into effect, and even then they would face the possibility of litigation by travelers, states, airlines, and perhaps others.

$3 billion dollars a year in extra fees for extra questioning of flyers

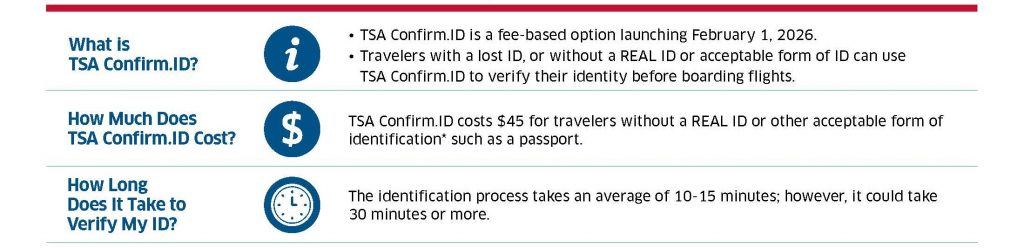

In its latest round of rulemaking by press release, the TSA has issued a series of procedurally irregular announcements indicating that the agency plans a new fee-based procedure for air travelers without “acceptable” ID, including those presenting ID that the TSA deems not to comply with the REAL-ID Act and those who don’t have or don’t show any ID at all:

- A notice published by the TSA in the Federal Register on November 20th said the fee for flying without ID or without REAL-ID would be $18 per person for each ten-day period.

- A second notice published on December 3rd, just two weeks later, announced that “based on review and revision of relevant population estimates and costs… and a revised methodology… TSA recalculated overall costs and determined that the fee necessary to cover the costs of the TSA Confirm.ID program is slightly more than $45.”

The drastic revision of the cost estimate and fee, so soon after the initial announcement, suggests that the initial estimate was sloppy, rushed, or both, and perhaps that the entire new program is being hastily implemented, may not yet be clearly defined, and may fit the definition of agency action that is “arbitrary, capricous, an abuse of discretion, or otherwise contrary to law”. Any such action is liable to be “set aside” by the courts on the basis of the Administrative Procedure Act (APA).

According to a press release posted on the TSA website on December 1st, “Currently, more than 94% of passengers already use their REAL ID or other acceptable forms of identification.” That’s only one percentage point higher than the 93% compliance the TSA announced after the first few weeks of REAL-ID “enforcement” in May 2025. These largely unchanged numbers suggest that the TSA is making little progress in persuading more travelers to sign up for a national-ID scheme or show their papers at TSA checkpoints.

Based on the current rate of roughly three million people a day passing through TSA checkpoints, 6% of whom don’t show ID the TSA deems “acceptable” (or don’t show any ID), 180,000 people a day would be assessed the proposed new $45 fee. That would generate $8.1 million a day, or $2.96 billion a year, in new revenue for the TSA.

The TSA’s initial notice claimed that currently “taxpayers pay[] for an individual’s identity verification services provided by TSA”. But each airline passenger already pays a fee of $5.60, collected by the airline, each time they pass through a TSA checkpoint at an airport.

This “9/11 Security Fee” was imposed when the TSA was created, and is supposed to cover the TSA’s costs of searching air travelers. Air travelers, not taxpayers, pay for the TSA to grope, interrogate, and delay us. Charging a fee for this “benefit” is like charging a “police user fee” to be pulled over in a traffic stop, even if no violation is found and no citation is issued.

In its initial Federal Register notice on November 20th, the TSA claimed that:

TSA has compiled a fee development report that provides a detailed discussion of the modernized alternative identity verification program’s expected costs, expected population, and fee determination. A copy of the fee development report can be accessed at TSA.gov.

In its follow-up notice on December 2nd, the TSA doubled down on this claim:

TSA has updated the fee development report that provides a detailed discussion of the TSA Confirm.ID program’s expected costs, updated expected population, and updated fee determination. A copy of the fee development report can be accessed at TSA.gov.

In fact, neither of these claims was true. There was no link to any initial or revised “fee development report” on the TSA home page on November 20th or December 3rd, and there was none there until late in the day on December 4th. As of this writing, searches for “fee development” report” on TSA.gov return no results related to “ID verification” or “TSA Confirm.ID”.

This isn’t the first time that the TSA has tried to base its policies and procedures on supporting documents cited or incorporated by reference in Federal Register notices, but not actually available to the public.

Obviously, the fee development reports are essential to any assessment of whether the fee setting was “arbitrary, capricious, or an abuse of discretion” and therefore in violation of the Administrative Procedure Act (APA). TSA officials signed off on lying official notices claiming that this information is publicly available, while keeping it secret until we let them know that we were about to publish a report calling attention to its unavailability and their lies about it.

The phone number in the “FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT” section of both Federal Register notices is 866-289-9673, which is answered by an an automated voice response system that plays recordings but doesn’t seem to provide any pathway through its menus to reach a human. (We’ve spent hours trying, unsuccessfully, over the years.) There’s an email address in the notices, “ORCACommunications@tsa.dhs.gov”, but we’ve received no response to messages sent to that address or to the TSA press office.

Finally, in response to our inquiries, late in the day on December 4th — more than two weeks after the initial Federal Register notice claiming that the initial report was already available — the TSA edited the Web page with its December 1st press release to add links at the bottom to the fee development reports:

- TSA Alternative Identity Verification Fee Development Report (November 13, 2025)

- TSA Confirm.ID Fee Development Report (December 2, 2025)

The fee development reports don’t reveal much about how the proposed system would work, but they do reveal a great deal about the TSA’s goals and increasingly wishful thinking.

Both fee development reports focus on how many people will be induced by the new fee to obtain and show REAL-ID to fly.

As of its November 13th report, the TSA predicted:

TSA forecasts that approximately 65.3 million air travelers will opt to use the TSA modernized alternative identify verification service over the first 5 years of the program. The Daily Users portion of the population estimate considers the historical average number of air travelers that do not have an AFOID [Acceptable Form Of ID] and will likely not obtain one. Historically, about one percent (25,102) of air travelers per day are in this grouping.

Reliance on this “historical” data is of course inappropriate, since during most of this “historical” period state-issued drivers licenses and IDs were considered “acceptable” by the TSA regardless of whether they were deemed compliant with the REAL-ID Act.

The relevant baseline is the period since May 7, 2025, when the TSA began to treat these noncompliant driver’s licenses and IDs as “unacceptable” (although still in fact accepting them as ID to fly). Since then, six to seven percent of airline passengers, or almost 200,000 per day, have showed up at TSA checkpoints with unacceptable ID.

The extortionate intent of the fee is made clearer in the TSA’s revised December 2nd report:

An individual that pays a fee to use the TSA Confirm.ID program may be motivated to obtain an AFOID in the future to present during future air travel. Thus, an air traveler makes an economic decision when choosing to continue seeking to use the TSA Confirm.ID program rather than obtaining and/or presenting an AFOID….

The total user population estimate consists of air travelers that arrive at a checkpoint with no AFOID. In total, TSA forecasts that approximately 10.6 million air travelers will opt to use the TSA modernized alternative identify confirmation service over the first 5 years of the program. The population estimate considers the number of air travelers that arrive at a checkpoint without an AFOID. TSA assumes that 6.4 percent of daily air travelers (154,946) arrive at a checkpoint without an AFOID…. Additionally, TSA is assuming that this population will decrease sharply in the first month upon implementation of the Confirm.ID program similar to the decrease experienced at the start of REAL ID enforcement in May 2025.

TSA believes air travelers will choose to obtain an AFOID, such as a REAL ID, rather than pay the fee and spend the additional time confirming identity or they will opt [for] an alternative method of travel. TSA further assumes this population will continue to decline by 10 percent monthly for two years, supported by a coordinated public affairs campaign. By year 4, TSA anticipates achieving a constant baseline of 1,530 daily air travelers arriving at a checkpoint without an AFOID, with half of them, 765 expected to pay for identity confirmation. The constant baseline is based on historic data on the number of daily calls to the National Transportation Vetting Center for identify confirmation during calendar year 2025.

This is bizarre, especially the prediction that “this population will decrease sharply in the first month upon implementation of the Confirm.ID program similar to the decrease experienced at the start of REAL ID enforcement in May 2025.” This is belied by the TSA’s own press release announcing the proposed new ID verification program, which says that REAL-ID compliance is currently 94% — only a slight increase from the 93% reported in the first weeks after the start of REAL-ID enforcement at airports in May 2025.

Based on this wishful thinking about American air travelers’ willingness to give up freedom for money, the TSA adjusted the per-person fee upward from $18 to $45 to cover the expected fixed costs of the new program.

This also suggests that, if most of the costs of the program are fixed, once the program is in place the TSA will keep raising the per capita fee as the number of travelers without acceptable ID is squeezed smaller and smaller, until the last holdouts and those whose ID has been lost or stolen are assessed a fee to fly of hundreds or thousands of dollars each — or more.

The real goal, these fee development reports make clear, is not aviation security but pressuring more people into the national REAL-ID database for unknown other uses.

The proposed new “ID verification” scheme makes no sense as a security measure, but it’s a carefully calibrated exercise in gradually and automatically escalating extortion.

When will the new “ID verification” fee and procedures go into effect?

The Federal Register notices both say that, “Collection of the fee will begin when TSA announces that individuals may register for the… program at TSA.gov.”

A press release and a new page about the proposal on the TSA website, attempting to set the effective date of a rule and fee schedule by press release and deliberately omitting it from the official notice in the Federal Register, say that the new procedure and fee for flying without ID or without REAL-ID will take effect February 1, 2026.

That’s less than 60 days from now — much too soon to complete the rulemaking, notice and comment, and information collection approval procedures required by the Privacy Act, the Paperwork Reduction Act, and the Administrative Procedure Act.

The announcement of this rushed date suggests that the TSA intends to ignore these legal and procedural requirements. We’re shocked! Shocked!

What will the new “ID verification” process be like?

It’s difficult to assess the TSA’s contemplated new ID verification scheme because the agency is working backwards. The TSA started by announcing the fee for a program none of the details of which have yet been disclosed and for which there is, as of now, no statutory basis or regulatory framework.

Is the TSA making the new ID verification program up as it goes along? Or is the real priority the fee announcement itself, as a threat that might extort travelers to get REAL-ID and show ID when they fly, with the ID verification program itself an afterthought? This would be consistent with the REAL-ID program as a whole, in which platitudes about “aviation security” and ID to fly have been invoked for twenty years as the pretexts for participation by states and individuals in the construction of a national ID database.

Another clue to a possible purpose of the proposed new ID verification scheme is contained in the TSA’s December 1st press release:

Identity verification is essential to traveler safety, because it keeps … illegal aliens out of the skies and other domestic transportation systems such as rail,” said Senior Official Performing the Duties of Deputy Administrator for TSA Adam Stahl.

Is one goal of this scheme to provide a mechanism for warrantless, suspicionless checks on the citizenship and immigration status of all travelers, and to turn TSA checkpoints for domestic flights into internal immigration checkpoints, if that hasn’t been done already?

Any foreign passport is considered “REAL-ID compliant”, regardless of the bearer’s US immigration status. Most foreigners in the US, regardless of immigration status, have passports from their countries of origin. “Illegal aliens” may thus be more likely to have REAL-ID than native-born US citizens who may never have needed a passport.

Requiring REAL-ID will do nothing to stop “illegal aliens” from flying unless the IDs of domestic air travelers are checked against some database of US immigration status.

Does the TSA plan to link Secure Flight and/or the proposed “TSA Confirm.ID” system to the USCIS “SAVE” database in its illegal new form as a national ID registry of all US citizens? Or is Senior Official Performing the Duties of Deputy Administrator Stahl’s invocation of “illegal aliens” just another xenophobic attempt to demonize foreigners as the pretext for more control and surveillance of US citizens’ movements within our own country?

According to the TSA, those paying the new extra $45 fee will be the “beneficiaries” of the TSA Confirm.ID program. For what “benefit” will these travelers be paying $3 billion a year More intrusive questioning? More delays? Denial of passage? All of the above?

Having to answer more questions is not a “benefit”. Travel by common carrier is the exercise of a right, not a privilege to be granted or denied by the government at whim.

The TSA says that travelers will have to “register for the modernized alternative identity verification program on the TSA website TSA.gov” and pay a fee “using TSA-approved payment methods, which may include collection by third parties”.

We assume that this means that, as with other countries’ fee-based online travel permit schemes, payment will have to be made online using a debit or credit card. This will force travelers without acceptable ID to link the TSA’s records of their air travel to their financial records.

The TSA’s notice gives scant detail on how, once a would-be air traveler has registered on the TSA website and paid the $45 per person fee, the new system will be different from the current (illegal) TSA procedures for people without an Acceptable Form Of ID:

The most common alternative identity verification service previously provided for individuals without an AFOID was establishing identity through the National Transportation Vetting Center, a TSA call-center that conducted knowledge-based identity verification. As part of the modernized alternative identity verification program, TSA is replacing this call-center with an automated, technology-supported service….

If an individual chooses to use the program and submit the required information, TSA will use the individual’s biographic and/or biometric information to verify identity and match the individual to their Secure Flight watch list result.

We don’t know how “TSA will use the individual’s biographic and/or biometric information to verify identity and match the individual to their Secure Flight watch list result”.

Will this rely — like the current system — on a game of “20 Questions” testing whether you know what’s in some data broker’s “garbage-in, garbage out” file about you? Will you have to submit a digital selfie for the TSA to try to match against some aggregated database of facial images collected for unrelated purposes — perhaps through the addition of photos from driver’s license records to the SPEXS national ID database? Will you have to submit copies of other documents, and if so which ones? Your guess is as good as ours.

If the identity of someone using the TSA app is “verified”, what will be the procedure when they get to the airport? How will the TSA know that a person who shows up at a TSA checkpoint is the same person whose identity was “verified” online?

Will you get a personalized secret code from the app — maybe in the form of a QR code? — to show at the checkpoint to prove that your ID has been “verified”? And if so, how will the TSA know that the person showing this code is the same person whose identity was previously”verified” online, unless they are going to go through the verification process all over again at the checkpoint?

Is this legal? Will it be challenged in court?

For years the TSA threatened that travelers without REAL-ID wouldn’t be allowed to fly, but it hasn’t actually tried to stop travelers without REAL-ID from flying. After REAL-ID “enforcement” began, the TSA website was changed to say that, “Passengers who present a state-issued identification that is not REAL ID compliant at TSA checkpoints and who do not have another acceptable alternative form of ID will be notified of their non-compliance, may be directed to a separate area and may receive additional screening.”

The new ID verification program will be “voluntary”, but the TSA says that, “Those individuals who do not have an AFOID and who choose not to use alternative identity verification or cooperate with the identity verification process will not be allowed to enter the sterile area of the airport.”

The TSA does not explain what, if any, legal basis it would claim for denying passage to these otherwise-qualified fare-paying common carrier passengers.

The only TSA authority over travelers without ID that has been approved by any court is the authority to subject them to some degree of more intrusive search of their person and baggage, as the alternative to having to show any ID at all.

So far as we know, no court has ever considered whether airline passengers or other travelers can be required to respond to warrantless, suspicionless administrative interrogatories. So far as we know, someone subjected to an administrative search of their person and/or possessions has the right to stand mute during the search.

Assertion by the TSA of authority to turn away travelers who don’t have or don’t choose to carry ID the TSA deems acceptable, or who don’t choose to “voluntarily” register and provide whatever answers to questions or other information or documents are demanded, would exceed the TSA’s statutory authority and violate the Constitution.

There’s no statutory basis for requiring travelers to identify themselves or answer questions in the absence of probable cause to suspect them of a crime, in which case they would have a Fifth Amendment right to remain silent.

Any law requiring travelers to identify themselves or answer other questions without probable cause would run afoul of the Fourth Amendment. Perhaps that’s why Congress has never even considered, much less enacted, such a law.

Airlines are common carriers, airports are public facilities, and the right of a ticketed passenger to pass through the airport and board a flight on a common carrier — without being required to identify themself or answer questions from police — should be the same as their right to walk down a public right-of-way without similar interference.

The problem is how to raise any of these objections to the TSA’s proposal in court.

42 U.S. Code § 1983, the Federal statute that was used in cases of Freedom Riders and other civil rights activists to challenge interference with interstate travel, creates a cause of action against individuals acting under color of state or local law, but not Federal law.

What’s needed is legislation such as the proposed Freedom to Travel Act that would create a similar cause of action against anyone interfering with the right to travel, including Federal agencies, agents, and contractors or others acting under color of Federal law.

Federal laws require the TSA to go through several largely bureaucratic procedures before they could legally put the proposed new ID verification scheme into effect. These don’t present a permanent bar to implementation of the TSA proposal. But there isn’t time to complete all of these steps properly by February 1, 2026. It remains to be seen if the TSA will postpone its plans, try to plead that an “emergency” justifies short-cutting these procedures, or ignore them and put the new system into effect prematurely and illegally.

Almost by definition, a new “registered traveler” program (which is how the TSA is categorizing its proposal) would require a new traveler registry for new purposes. That would constitute a new “System of Records” as that term is used in the Privacy Act, and/or new categories of data, data sources, data subjects, and routine uses.

The Privacy Act requires any Federal agency to provide 30 days notice in the Federal Register and an opportunity for public comment before any new or revised system of records is put into effect. Maintaining a new or revised system of records without this notice is a crime on the part of the responsible agency officials and employees.

In practice, none of these official criminals are ever prosecuted. But it’s possible to bring a civil lawsuit under the APA to “set aside” an agency action including the maintenance of a system of records without proper notice, as is happening now with litigation against the conversion of the USCIS “SAVE” immigration database into a national ID registry including all US citizens.

There’s precedent with TSA attempts at rulemaking by press release. A lawsuit brought by EPIC under the Administrative Procedure Act forced the TSA to conduct (after the fact) notice and comment rulemaking on its deployment of virtual strip search (“whole body imaging”) machines.

Creation of a $3B/year program is a “major” agency action, pursuant to the APA, requires prior notice and opportunity for public comment. There’s also at least an arguable question as to whether this is what Congress meant by a “registered traveler” program — a strained claim being made by the TSA to bootstrap the basis for the proposed fee.

The Paperwork Reduction Act (PRA) requires prior approval from the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB) for any “collection of information” from the public.

It’s unlikely that OMB would turn down a request from the TSA for approval of its proposed new ID verification program. But (1) the TSA hasn’t yet started the process of requesting and obtaining OMB approval, and (2) that process takes more time than the TSA has available before February 1, 2026. Here also, it’s too soon to tell whether the TSA will set back the start-up date in its press release, try to plead that an “emergency” justifies short-cutting PRA procedures, or ignore them and put the new system into effect prematurely and illegally.

The TSA has never gotten OMB approval for either aspect of its current ID verification system for travelers without ID or with unacceptable ID, which involves both an unapproved ID verification form (TSA Form 415) and the unapproved collection of answers to a series of stupid questions about what information a data broker has in its files about you. The current TSA ID verification system involving the collection of this information without OMB approval has been illegal, in its entirety, since the TSA started using it in 2008.

The PRA requires a two-step notice-and comment process before OMB can approve a new or revised collection of information. First the agency must publish a notice in the Federal Register of its intent to request approval for the new or revised collection of information, and give the public 60 days to submit comments to the agency on the proposal. If and when the agency decides, after the close of that comment period and consideration of those comments, to submit the proposal to OMB for approval, it must publish a second notice and allow another 30 days for submission of comments directly to OMB.

The TSA has twice, under the Obama (2016) and Trump 1.0 (2020) Administrations, given notice of its intention to request approval from OMB for TSA Form 415, “Verification of Identity”. These notices have been premised on the false assumption that ID is required by law to fly. Each time, the TSA has abandoned its plan to request approval of any ID verification form, without submitting it to OMB, after The Identity Project and others objected to the proposals as contrary to existing laws and Constitutional and human rights.

If the TSA were to start over today, the two-stage PRA notice-and-comment process would take at least 90 days, unless OMB gives interim approval to the new collection of information about travelers without ID on the basis of some purported “emergency”.

The TSA has tried to get Congress to exempt the REAL-ID program and related activities from the PRA and the notice-and-comment provisions of the APA, but Congress has declined to do so.

The PRA creates very strong protections for individuals in the form of an absolute defense against any penalty for not providing information if the collection of information doesn’t comply with the notice and approval requirements of the PRA. That would seem to apply to anyone assessed an administrative fine or charged with a crime for proceeding through a checkpoint without providing information for ID verification. But you can only try to invoke that defense — or find out whether a court will accept it — after you have been charged with a crime or assessed a fine. It’s an inherently high-risk gamble.

States may have a stronger basis than individuals, as well as more resources, to challenge the TSA’s interference with the equal right of their residents to interstate travel on Federally licensed common carriers. No state actually complies with the mandate of the REAL-ID Act for a compliant state to share its driver’s license and ID database with all other states.

The ideal plaintiff state would be one that has enacted legislation prohibiting its driver licensing agency from issuing licenses compliant with the REAL -ID Act or uploading data about state residents to the SPEXS national ID database. If SPEXS is part of the “TSA Confirm.ID” ID verification process or algorithm for deciding who to allow to fly, any state that hasn’t chosen to upload its residents’ data to SPEXS — such as California, Illinois, or Connecticut — might be in a position to challenge interference with its residents’ travel.

Airlines and state and local government agencies that operate public airports might also have standing to challenge the TSA’s interference with their customers’ and users’ right to travel. Sadly, this is unlikely. Airlines and airport operators have been willing and enthusiastic collaborators with law enforcement agencies worldwide, even the worst human rights violators, in public-private partnerships for travel surveillance and control.

Regardless of the basis for a lawsuit, the TSA would probably try to argue that its checkpoint staff have absolute or qualified immunity from lawsuits, and/or that the Federal government hasn’t waived its sovereign immunity for the specific claims in the complaint.

You might have more success bringing a lawsuit for denial of passage through a checkpoint at San Francisco International Airport (SFO) or Kansas City International Airport (MCI), the two major US airports where checkpoint are staffed by contractors, not TSA employees. The TSA would probably try to claim some sort of derivative immunity for its contractors. That’s an important legal issue, but so far as we can tell would be a case of first impression.

We welcome other ideas for legal challenges to this proposed travel surveillance and national ID scheme — preferably before, rather than after, the TSA tries to put it into effect.

What will happen if I say, “No”?

No statute or case law authorizes the TSA to do anything more than subject you to extra-special groping and ransacking of your luggage if you don’t show ID.

In practice, we suspect that what the TSA intends — unless so many people push back that it has to walk back this illegal proposal — is that the document checker at the entrance to the checkpoint will tell you you aren’t allowed to proceed any further

That will leave you with three choices:

- If you leave the checkpoint when the document checker tells you you can’t fly, you probably won’t be arrested or fined (although we can’t be responsible for the actions of a lawless agency like the TSA, or of local police who often arrest people first, if the TSA asks them to do so, and make up a pretext later to try to justify the arrest). But if you give up and go away, you may have a hard time establishing a cause of action in court.

- If you don’t leave the entrance to the checkpoint when the document checker tells you to do so, they will eventually (a) call the local police to deal with you, with unpredictable consequences that might include arrest, and/or (b) impose an “administrative fine” on you for “interfering with screening“. You might beat the charges in local court, or they might not decide to press charges once they’ve removed you from the airport. But fighting an administrative fine from the TSA is an arduous process that involves first a kangaroo-court hearing before an administrative law judge (ALJ) and then — assuming that the ALJ rules against you, which they probably will — an expensive appeal to a Federal Circuit Court of Appeals.

- If you ignore the document checker and keep walking toward or past the checkpoint, checkpoint staff will almost certainly call the police, and they will almost certainly arrest you, possibly on more serious Federal criminal charges. (TSA checkpoint staff don’t have the legal authority to arrest or physically restrain you, and they are trained not to physically restrain travelers, although they sometimes do.) The TSA might also assess a much larger administrative fine against you, but that will be the least of your problems. You’ll get your day in court, and there are arguments against the TSA’s demands for information and denial of passage through the checkpoint to get to your flight that you might only be able to raise in defense against criminal charges. The best defense, surprisingly, might be pursuant to the Paperwork Reduction Act. But a risk of Federal criminal charges is not something to be taken lightly.

We hope that impact litigators, state governments, and/or airlines challenge this proposal, or that Congress comes to its senses and enacts the REAL-ID Repeal Act and the Freedom to Travel Act, before air travelers have to confront this unsavory set of options.

Tell Congress to act — now! Tell state legislatures to opt out of REAL-ID. And tell state Attorneys General and airlines to prepare to stand up for their residents and customers by challenging this dangerous TSA proposal in court at the earliest opportunity.

A true air travel ban for non-REAL-ID holders seems like the logical and fair approach. The rationale for this program clearly seems to be to urge citizens of states, like WA, that stonewalled REAL-ID for many years, to comply. The stonewalling states correlate strongly to the most liberal sanctuary states. So illegal aliens may be able to register to vote in these states, but is there a ‘right’ to use the US air transportation system? And illegal aliens can always use passports to fly – they just have to be careful to not ever show them in their states where they are physically located most of the time.

The TSA is the ATF of travel. Make it up as they go along and zero oversight. Americans need to boycott air travel. Plain and simple.