ARC sells airline ticket records to ICE and others

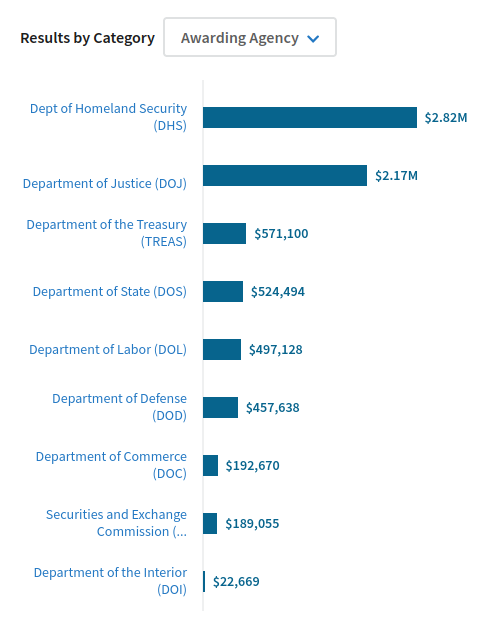

Contracts by Federal agencies with the Airlines Reporting Corporation for access to reports of airline tickets issued by US travel agencies, from USAspending.gov.

A company you’ve probably never heard of is selling copies of every airline ticket issued by a travel agency in the US to the US Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and a plethora of other Federal law enforcement and immigration agencies — and who knows who else.

Records of all airline tickets issued by travel agencies in the US are being sold to US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and other Federal law enforcement agencies, according to an ICE procurement document posted yesterday on a US government contract website and uncovered in a major scoop today by Katya Schwenk of Lever News.

According to the document found by Ms. Schwenk on SAM.gov, ICE is entering into a no-bid contract with the Airlines Reporting Corporation (ARC) “to procure, on a sole source basis, licenses for Travel Intelligence Program (TIP)… The vendor listed is the only company that can provide the required software licenses.”

ARC is the financial clearinghouse through which travel agencies in the US (from mom-and-pop agencies to online mega-agencies like Expedia) pay airlines (including both US and foreign airlines) for the tickets those agencies have sold. Its role is similar to that of VISA and MasterCard for credit card merchant transactions, except that VISA and MasterCard compete with each other, while ARC has no competitor in the US. A few travel agencies have special arrangements to pay certain airlines directly, bypassing ARC for tickets those agencies issue on those airlines only, but that’s the exception.

Ticket sales by travel agencies in the US are reported daily to ARC through links to computerized reservation systems. Every week, each travel agency in the US submits a report to ARC with a copy of every ticket it has issued, the amount paid, the fare calculation and tax breakdown, and the form of payment. ARC takes the total for the week’s sales on all airlines out of the agency’s bank account, and pays each airline a weekly total for its tickets issued by all agencies accredited through ARC. (The amount transferred to or from the agency is the net total, taking into account ticket sales, refunds, any commissions to the agency from airlines, “debit memos” when an airline disputes the fare originally collected by the agency, and whether credit card charges have been processed by the agency or the airline as the merchant.) Copies of tickets are included with agencies’ reports to ARC so that airlines can audit that agents have charged the correct fare. ARC is a joint venture owned by just a few airlines, but provides settlement services to more than 200 other airlines.

(ARC only handles payments from travel agencies in the US. Payments and credits to airlines from travel agencies in countries other than the US are settled through other regional financial clearinghouses under IATA’s Billing and Settlement Plan, BSP.)

The amounts paid to ARC by Federal agencies aren’t large enough to make selling data to the Feds a significant line of business for ARC. But the amounts are large enough to indicate that Federal law enforcement and immigration agencies are using information about airline tickets obtained from ARC in a significant and growing number of cases, for unknown purposes and on an unknown legal basis.

We’ve never heard of the “Travel Intelligence Portal” through which ARC offers access to ticket records before now. TIP isn’t mentioned anywhere on ARC’s website, in ARC’s privacy policy, or in the privacy policy of any airline or travel agency we’ve reviewed. Travelers and ticket purchasers who don’t know that ARC exists aren’t likely to ask what it has done with their data. We don’t know whether TIP is a service offered by ARC exclusively to Federal agencies, or if it has other government or commercial users in the US and/or abroad.

The previously unnoticed ARC contracts with ICE and other US government agencies also raise substantial doubt as to whether travel agencies or airlines — including foreign airlines that process payments for their ticket sales in the US through ARC, and travel agencies that act as their agents in the US — are complying with foreign laws including PIPEDA in Canada and the GDPR in Europe.

If ARC is selling ticket data to the US government without reporting those disclosures to the travel agencies and airlines involved, those agencies and airlines will be unable to provide data subjects with an accurate or complete accounting of the disclosures of their personal data, as required by PIPEDA and the GDPR.

On the other hand, if travel agencies and/or airlines have authorized ARC to make this data available to the US government, or have continued to transmit data to ARC after learning that ARC was making it available to the US government, those travel agencies and/or airlines have likely violated their duty not to transmit personal data to entities that can’t not assure adequate protection of that data against onward disclosure.