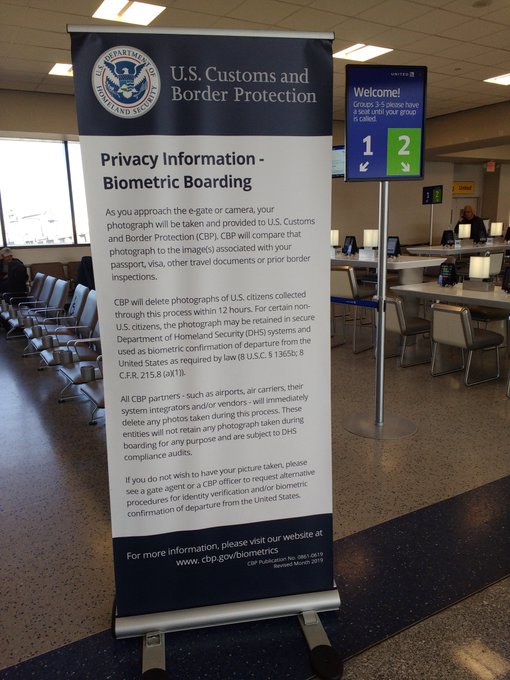

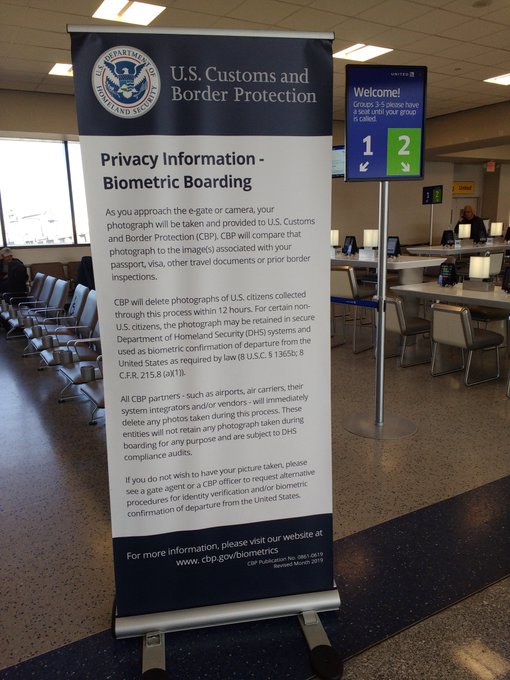

[CBP sign at biometric boarding gate at Newark Liberty International Airport. Note the absence of the OMB Control Number and other notices required by the Paperwork Reduction Act.]

[CBP sign at biometric boarding gate at Newark Liberty International Airport. Note the absence of the OMB Control Number and other notices required by the Paperwork Reduction Act.]

Repudiating the principles for assessment of biometric identification of travelers it adopted in December 2019, and effectively mooting the policy development process it had begun since then, the Port of Seattle Commission voted unanimously today to authorize a $5 million, ten-year contract to purchase and install Port-owned common-use cameras and facial recognition stations at all 30 departure gates of a new international terminal.

The Port issued a detailed, self-congratulatory press release within minutes after the vote, which strongly suggests that Port staff knew how the Commissioners would vote before today’s charade by the Commissioners of taking comments from the public and “debating” the issue even began.

Behind the scenes, US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) appears to have been playing hardball, using the typical law enforcement line of, “We’re going to do this to you anyway. You can either choose to make it easy for us, or we’ll make it hard on you.” The Seattle Times reported after the Port Commission vote that CBP recently began fingerprinting non-U.S. citizens boarding some international flights at Sea-Tac Airport. It seems likely that the implicit or explicit threat by CBP was that if the airport didn’t install and deploy automated facial recognition to track passengers, CBP would use a more humiliating form of biometric tracking, fingerprinting departing non-U.S. citizens the way it already fingerprints non-U.S. citizens when they arrive in the U.S.

The choice for the airport and its governing board was whether to collaborate with CBP. Port Commissioners seemed to want to reign in CBP. But at the end of the day, they proved unwilling to assert their authority as an elected public oversight board against the malign convergence of interest between government agencies, airlines, and Port staff who identify with the police and the airline industry more than with the public. The Port Commissioners chose to have the airport actively collaborate with and front for CBP, at the airport’s expense, rather than dissociating itself from CBPs flagrantly illegal activities, making CBP do its own dirty work at its own expense, or trying to mitigate the damage through signage informing travelers of their rights.

The Port press release claims that “the Commission’s goal is to replace CBP”, but that’s clearly false and appears intended to mislead the public. In fact, the sole purpose of the cameras and software to be purchased by the Port is to augment, not replace, the ability of CBP to use, retain, and share photos as its sees fit. Every photo of a traveler taken by the Port cameras will immediately be sent to CBP. There’s no plan to replace CBP, deny it access to any photos, or expose its secret algorithms and secret biometric databases.

All of the comments from the public to the Port Commission on this issue, as members of the Commission acknowledged, were opposed to the Port collaborating with CBP on facial recognition or spending Port money to do so. Members of the public, including experts in cybersecurity and threat modeling, pointed out that many key questions about the Port’s proposal and CBP’s and airline’s practices, plans, and policies remain unanswered. Most urged the Commission to reject the proposal outright and withdraw its request for bids for facial recognition equipment. All commenters agreed that approval of the procurement contract would be premature until more information is made available to the public and the current policy development process is completed.

In our latest written comments to the Port Commission today, which we summarized in person at today’s meeting (see also our previous submissions to the Port Commission on December 10, 2019, and February 25, 2020), we pointed out that:

The proposed procurement and deployment would violate Federal law, the norms of Fair Information Practices (FIPPs), and the professed “principles”, including FIPPs, of both the Port and US Customs and Border Protection (CBP). It should be rejected, and the RFP for this project should be withdrawn or, at a minimum, postponed….

It isn’t just that CBP is violating the Privacy Act, or that collecting facial images and sending them to CBP would make the Port complicit in this violation of Federal law. The violation of the Privacy Act by CBP lies specifically in CBP’s outsourcing the collection of this personal data to the Port, airlines, or any other non-Federal entities.

This provision was and is included in the Privacy Act for good reason. The Port should heed it, and make CBP comply with Federal law by collecting any personal data it uses for making decisions about individuals, including facial images of travelers, directly from those individuals. CBP could collect this data itself at Sea-Tac, as it does at some other airports. It doesn’t want to, but it has clearly demonstrated that it could do so.

If there is one lane at a departure gate, or on arrival, where a uniformed CBP agent is photographing travelers, and one lane without a Federal law enforcement officer with a camera, travelers will have a much clearer and more informed choice – and one that, unlike the proposal before the Port Commission, might comply with the Privacy Act.

Port Commissioners claimed, quite implausibly, to think that having the Port install and operate the cameras would give the Port some control of how CBP uses the photos after the Port sends them on, or at least more control over signage. But CBPs “Biometric Air Exit Business Requirements” for its airline and airport “partners”, which were finally disclosed only two days ago in response to our request, and were never provided to or reviewed by the Port’s “Biometrics External Advisory Group” (BEAG), tell a different story about who’s in control. As we explained in our comments:

Some Port staff, in their proposals to the BEAG and the Port Commission, have suggested that by owning and operating facial recognition systems the Port would have more control over signage and other notices provided to the public to enable more informed consent and mitigate the harm to the public of CBP’s (illegal) activities.

But in fact, the proposed procurement would have exactly the opposite effect. By agreeing to comply with CBP’s “Requirements” – which are explicitly incorporated by reference in the RFP and the proposal for action by the Port Commission – the Port would be tieing its own hands and committing itself to display CBP’s signs – regardless of their truth or falsehood or their compliance with the law – and not to display any signage, make any announcements, or provide any information not approved by CBP.

Item 8 of CBP’s “Requirements” would prohibit the Port from posting any signs or distributing any communications pertaining to CBP’s use of biometrics without CBP’s prior approval.

Item 13 of CBP’s “Requirements” would obligate the Port to post whatever signage CBP demands, regardless of whether the Port considers it inaccurate, misleading, or incomplete.

In effect, these provisions would amount to a (self-imposed) gag order not to criticize CBP, and a (self-imposed) agreement to serve as a mouthpiece for CBP propaganda, regardless of its truth or falsehood. Rather than enabling the Port to mitigate the harms of CBP’s (illegal) practices through more or better signs or announcements, the proposed action by the Port Commission would prevent the Port from doing so.

If CBP fails – as it has failed to date at Sea-Tac and all other airports with biometric departure gates – to post the notices required by the Paperwork Reduction Act, informing individuals, regardless of citizenship or immigration status, of their right not to respond to any Federal collection of information that does not display a valid OMB Control Number and PRA notice, the Port itself should post such notices at all gates. But the Port won’t be able to do so without CBP approval (which wouldn’t be likely to be granted) if the Port Commission approves the proposal on your agenda for action today.

Port Commissioners approved a motion declaring that CBP’s uses of facial recognition at airports are “lawful”, while simultaneously and hypocritically dismissing our objections to CBP’s flagrant violations of Federal law by saying that, “We’re not judges. If a court says it’s illegal, we won’t do it.” This ignores the fact that, as we also noted in our comments, CBP and DHS have promulgated regulations exempting the databases in which they store facial images from the rights otherwise available to individuals under the Privacy Act to access, accounting of disclosures, and civil remedies for violations. This makes it all but impossible to have CBP’s practices reviewed by the courts.

Today’s decision by the Port of Seattle Commission sets the worst possible national precedent. But it doesn’t render the Port’s ongoing process of developing policies for use of biometrics at Sea-Tac entirely irrelevant. We will continue to monitor the process and engage with the Port Commission as it considers use of facial recognition (in collaboration with, and sending passenger photos to, CBP and perhaps in the future the TSA) by airlines and other commercial entities for their own purposes.

As we noted in response to the first draft of a Port of Seattle policy for “non-Federally mandated” uses of biometrics:

Missing from that draft is any explanation of the purpose or justification for airlines to identify passengers, independent of any Federal mandate.

Airlines could, and did, operate for decades without requesting ID from passengers. Airlines began asking (but not requiring) passengers to identify themselves only when they were ordered to do so by the FAA (the predecessor of the TSA). The only lawful reason for airlines to ask passengers for ID is to satisfy a government mandate.

As common carriers, airlines are required to transport all passengers, regardless of who they are, and are required to sell tickets at prices determined by a public tariff.

An airline cannot lawfully “reserve the right to refuse service”. It cannot lawfully personalize prices or charge different prices based on passengers’ identities.

So why do airlines think they “need” to identify passengers at all, by any means?

One cannot assess the justification (or lack thereof) for biometric identification of travelers for non-Federally mandated purposes without first assessing the justification (or lack thereof) for identification of travelers generally for such purposes.

This assessment is entirely absent from the draft recommendations for Port policy, but is essential.