Five years after we requested them under the Freedom Of Information Act, the TSA has released a redacted copy of its Identity Verification Call Center (IVCC) procedures for interrogation and “screening” of people who show up at TSA checkpoints without ID or with ID the TSA initially deems unacceptable.

Most of these people — 98% of them, according to summaries and logs eventually released to us by the TSA in response to our FOIA request — are eventually “allowed” by the TSA or TSA contractors to exercise their right to travel by common carrier, but only after being put through the TSA’s identity verification procedures.

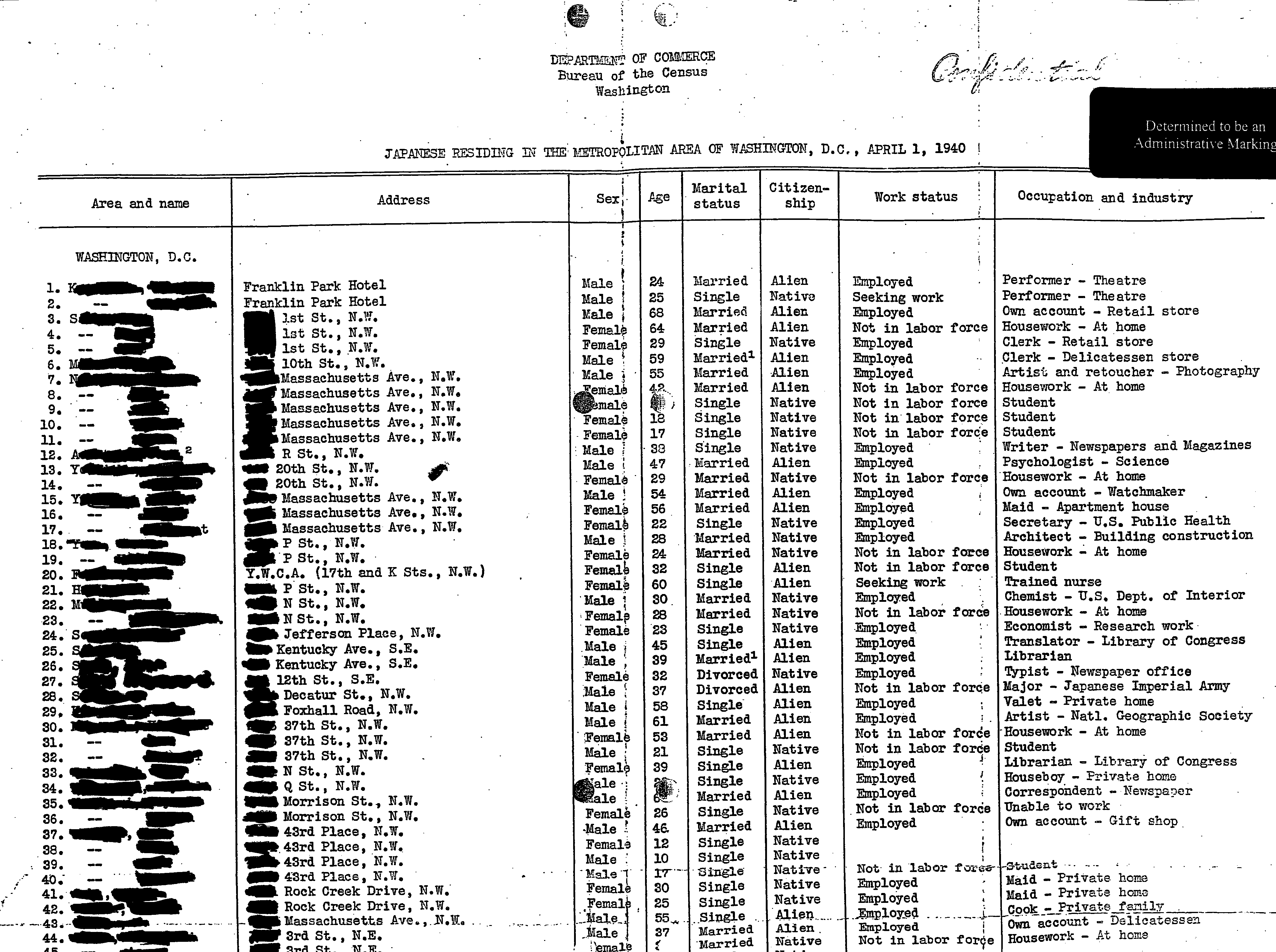

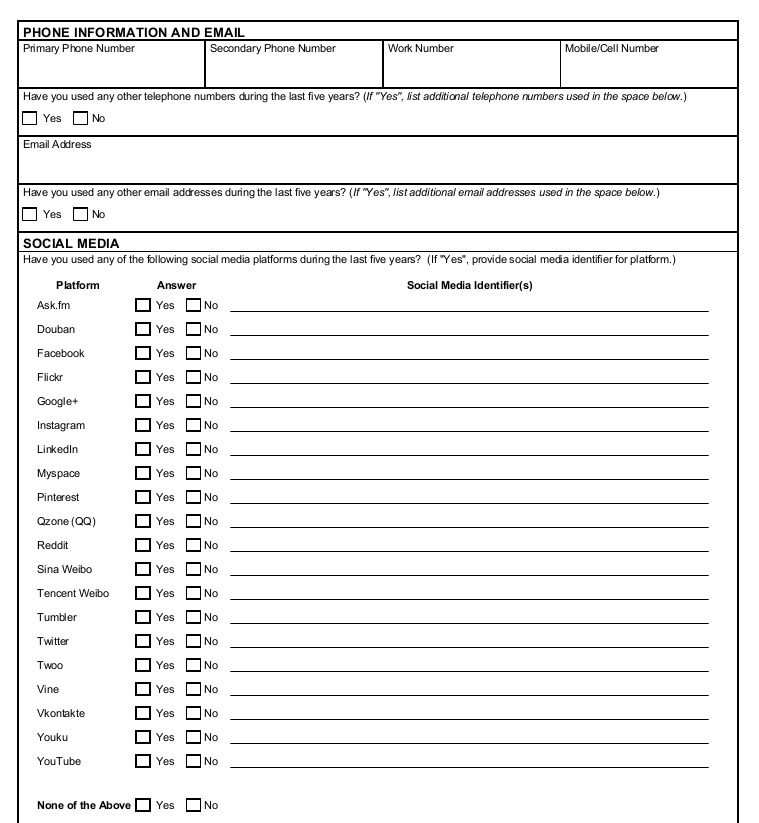

The TSA’s Standard Operating Procedures for travelers without ID or with initially unacceptable ID include requiring them to complete and sign an (illegal) TSA Form 415, “Certification Of Identity” (COI), and playing a pointless game of 20 questions by telephone with the ID Verification Call Center to see if the traveler’s answers to questions match the information in the files secretly maintained by a commercial data broker, the Accurint division of LexisNexis (part of Reed Elsevier).

In 2013, we asked the TSA for its records of what happens to people who try to fly without ID or with ID that the TSA or its contractors initially deem unacceptable. As part of the same request, we asked for related email messages and policies.

The TSA dragged its feet for years, gradually releasing a trickle of redacted and scanned page-view images of derivative reports, but none of the email messages or reports.

A year ago, the TSA declared its munged partial response “complete”. We filed an administrative appeal, and six months later, the TSA’s appeal officer partially upheld our appeal and remanded our request for a further search for email messages and policies.

After eight more months, we’ve finally received a redacted image of the 2013 version (the version in effect when we first made our request) of the TSA’s ID Verification Call Center “Standard Operating Procedures”.

By the time the TSA finally looked for the email messages on which some of the reports were based, after our appeal was upheld, those messages had all been deleted:

No email messages pertaining to the responsive records were located. The email account utilized to prepare and distribute the TSOC reports was centralized into the National Transportation Vetting Center email account, and all emails created during that time associated with the TSOC reports already released to you have been deleted.

Ultimately, the ID Verification SOP leaves the final decision on whether a would-be airline passenger is allowed to travel to the standardless discretion of the TSA staff person in charge for each airport, the Federal Security Director (FSD) or their designee.

There are some other curious statements between the redactions in the version of the ID Verification SOP released to us by the TSA.

According to the SOP:

Under these procedures, passengers are required to produce acceptable identification to a TSA Screening Representative (TSR) before proceeding to the security checkpoint. Passengers who do not produce acceptable identification and who fail to assist TSA personnel in adequately identifying their identity will be denied entry.

There is no indication of the legal basis, if any, for this TSA claim that airline passengers have an affirmative duty to “produce acceptable identification” or “assist TSA personnel in adequately identifying their identity”, or what the basis would be for denial of passage.

The SOP also contains a bizarre assertion in section 2.5.9 of the SOP that the COI form (TSA Form 415), which travelers without ID or with unacceptable ID are required to complete and sign, is “Sensitive Security Information” (SSI) which is “not to be circulated to the public” and which passengers must surrender to checkpoint or TSA staff on demand. The SOP doesn’t say how this form could be held to constitute SSI.

TSA Form 415 has already been made public in response to another of our FOIA requests, and the Paperwork Reduction Act requires that forms used to collect information from the public be published for comment before they are approved.

In 2016, after using Form 415 and its unnumbered predecessor illegally for years, the TSA published a notice that it planned to apply for approval of this form (to which we objected). But the TSA has yet to apply for, much less receive, the approval it would need before using this form.