Human Rights and “Countering Terrorist Travel”

In late 2023 the U.N. Special Rapporteur on Counter-Terrorism and Human Rights released perhaps the most significant independent assessment to date of the human rights implications of travel surveillance and control.

The Special Rapporteur’s report was released without publicity on the next-to-last day of the Special Rapporteur’s term. Aside from an article by Statewatch, it got little notice.

A year later, an update from Privacy International reminds us of the Special Rapporteur’s report and calls attention to how little its recommendations have been heeded — and how urgently important they remain.

The Special Rapporteur’s report provides both a call to action and an analysis of travel surveillance and control as a human rights issue.

The report by Special Rapporteur Fionnuala Ní Aoláin and her staff reviewed the U.N. Countering Terrorist (CT) Travel Programme and the goTravel software being provided by the U.N. to its member states for them to use in monitoring and controlling travel worldwide on the basis of airline passenger manifest (API) and reservation (PNR) data.

This wasn’t the first time that the Special Rapporteur has addressed the use of API and PNR data for travel surveillnace and control. But it was the most detailed assessment by to date any of the U.N. human rights bodies of the system of travel surveillance and control based on airline reservations against the norms of international human rights law. The Special Rapporteur’s report addressed privacy — the focus of the recent follow-up by Privacy International — but also other human rights including, perhaps most importantly, the right to freedom of movement.

In the considered judgement of the Special Rapporteur as the holder of the relevant human rights mandate within the U.N. framework, this system fails the test of human rights law. “The roll-out of the system must be paused and an urgent review initiated”:

This position paper carries out an in-depth analysis of human rights implications and concerns associated with the CT Travel Programme and its promulgation of goTravel. The position paper demonstrates how UNOCT and its UN implementing partners appear to be failing to adequately mainstream human rights in the development of the underlying system for collection, use, and sharing of API/PNR data, and how the system which is now being rolled out internationally at pace, risks squarely contravening international law, particularly international human rights law, in multiple respects….

The CT Travel Programme’s API and PNR collection and sharing system was never designed with human rights in mind. It is marked by ad hoc thinking and the absence of rigorous analysis of how the technology and the international framework for data sharing it facilitates could be designed and operated in a manner which complies with relevant legal obligations, particularly international human rights law. The absence of that analysis has led to a situation in which the UN is now directly implicated in an approach to API and PNR data collection and sharing being rolled out globally which risks placing immensely powerful tools in the hands of States which may misuse them, intentionally or inadvertently, to jeopardize human rights, without any evidence of sufficient prior vetting, and without any practical or legal recourse to prevent or sanction such misuse….

The current UN approach to API and PNR data collection and sharing which is facilitated by the UNOCT and UN implementing partners in the CT Travel Programme and go Travel software platform represents a profound human rights risk and a serious reputational risk for the UN itself.

The Special Rapporteur’s report notes, with appropriately grave concern, that the U.N. itself has mandated — as we have reported — that the government of each U.N. member state must establish an airline passenger surveillance and control agency (“Passenger Information Unit”), compel airlines to provide the government with mirror copies of airline reservations (PNRs), and make that data available on request to all other U.N. members.

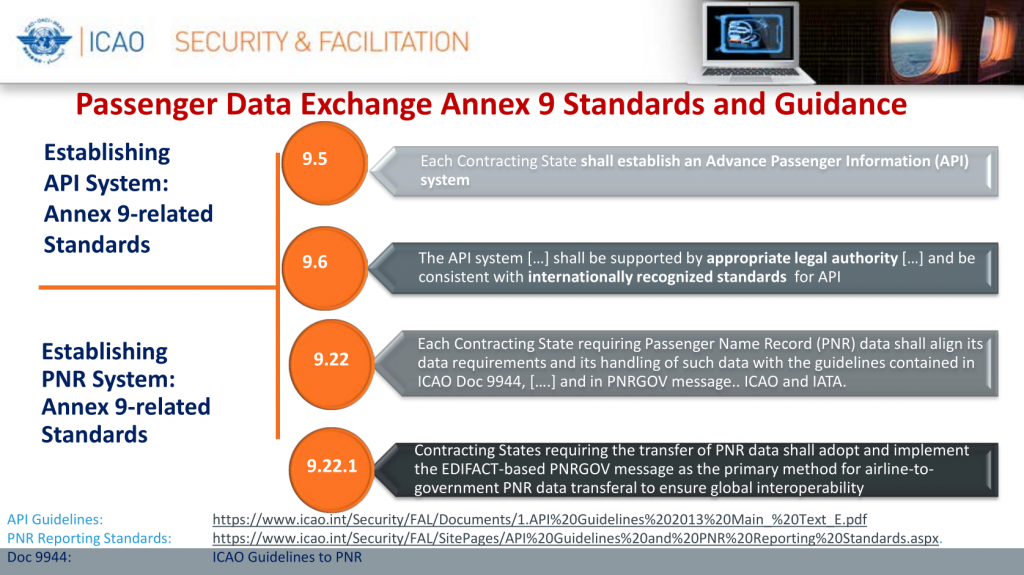

These requirements have been imposed through resolutions adopted by the U.N. Security Council and standards adopted by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), the U.N.-affiliated body assigned responsibility for implementation of aviation treaties.

In addition, as we have also reported, the U.N.’s Countering Terrorist Travel Programme is providing U.N. members with free “goTravel” software to use in tracking and control of air travelers on the basis of data obtained from airlines.

According to the Special Rapporteur:

The design, implementation, and spread of the global API/PNR data collection and sharing regime poses substantial potential risks to human rights which cannot be addressed by inadequate mitigation strategies at the back end. The implication of the UN’s engagement in this scale and scope of international data sharing is deeply concerning…. The scale and scope of data engagement… expose the United Nations to potential responsibility for human rights abuses stemming ultimately from the CT Travel Programme and goTravel.

The Special Rapporteur notes that, rather than reflecting privacy or human rights by design, API and PNR-based travel surveillance and control schemes are built on pre-existing commercial systems not designed with government use or human rights in mind:

It is important to recognize from the outset that the CT Travel Programme and its centrepiece — the goTravel software — are not the product of considered inter-State and multi-agency negotiation on agreed requirements and safeguards, but rather entail the opportunistic co-opting of air carrier API and PNR protocols to serve counter-terrorism and security purposes for which those commercial passenger datasets were never originally devised….

Claims that this travel surveillance and control will be carried out in such a manner as to respect human rights appear to be unsupported pro forma rhetoric:

The statements by the proponents of the CT Travel Programme and goTravel system that recipient Member States are supported to ensure that human rights-respecting frameworks are in place prior to provision of goTravel and that the goTravel software is ‘compliant with human rights, privacy and data protection principles by design’ ring hollow and appears to have no concrete action or ongoing oversight point attached to it.

Although human rights impact assessments of these schemes were supposedly conducted, they were carried out after the fact and by the governments using these systems, not by independent entities or those with a human rights focus. “The Special Rapporteur notes with regret that her mandate was not consulted” in the development of these systems.

The UN and ICAO mandate for sharing of API and PNR data with even the worst human rights violators among UN and ICAO member states is cause for special concern:

Of the current 65 beneficiary States – those participating in the CT Travel Programme and on the path to receipt of the goTravel system – there are a number of States with extremely concerning records of systematic human rights abuse, particularly in respect of the sort of surveillance and persecution of dissidents and journalists which API/PNR data systems facilitate. One of these States is currently subject to the Security Council sanctions regime…. Further, UN human rights treaty bodies have consistently expressed concerns in respect of a range of proposed beneficiary States… in respect of a wide spectrum of human rights violations ranging from torture, inhuman treatment and arbitrary detention to violations of the right to privacy, free expression, and political participation. The Special Rapporteur is profoundly concerned that the provision of powerful data monitoring tools to regimes with histories of such violations either indicates that rigorous analysis of human rights concerns cannot have been conducted, or, if conducted, cannot have been afforded sufficient weight.

Surveillance of travelers through government access to and sharing of airline reservations implicates privacy and freedom of expression, among other human rights:

First, with respect to the right to privacy (and the various rights of expression, religion, political participation, etc which depend upon privacy), the sensitivity and risks represented by API and PNR data is difficult to overstate. Both API and (to a greater extent) PNR data comprise rich datasets because they provide not only biographical information but also further data points (about movements and, in the case of PNR, financial transactions, companions, address etc) which hold the promise of more precise conclusions about each person’s activities and connections. The existence of such datasets which combine location information, financial connections between people, and their physical travel histories means that those State authorities with access to the data can identify where a person has travelled, with whom, and at whose expense.

Privacy and freedom of expression aren’t the only human rights implicated by government access to and use of airline passenger manifest and reservation data. Governments use this data to restrict the right to freedom of movement and the right to seek asylum, through control of who is allowed to board airline flights:

Another unique human rights challenge presented by the use of API and PNR data in screening is that, because such data are provided well ahead of travel, it may lead to individual travellers not only being subject to screening on arrival, but to denial of boarding and departure altogether. Such an outcome is in tension with fundamental rights to freedom of movement and, crucially, the right to seek asylum overseas….

As the recent UN OCT Handbook on Human Rights and Screening in Border Security and Management notes, ‘[d]enial of boarding may put an individual at risk, and may deprive them of the opportunity to seek asylum’ upon arrival in another country. The General Assembly has underscored that States must ‘adopt concrete measures to prevent the violation of the human rights of migrants while in transit, including in ports and airports and at borders and migration checkpoints.’

Unfortunately, denial of boarding by airlines to asylum seekers isn’t just something that might happen. It’s a shared goal of governments and airlines.

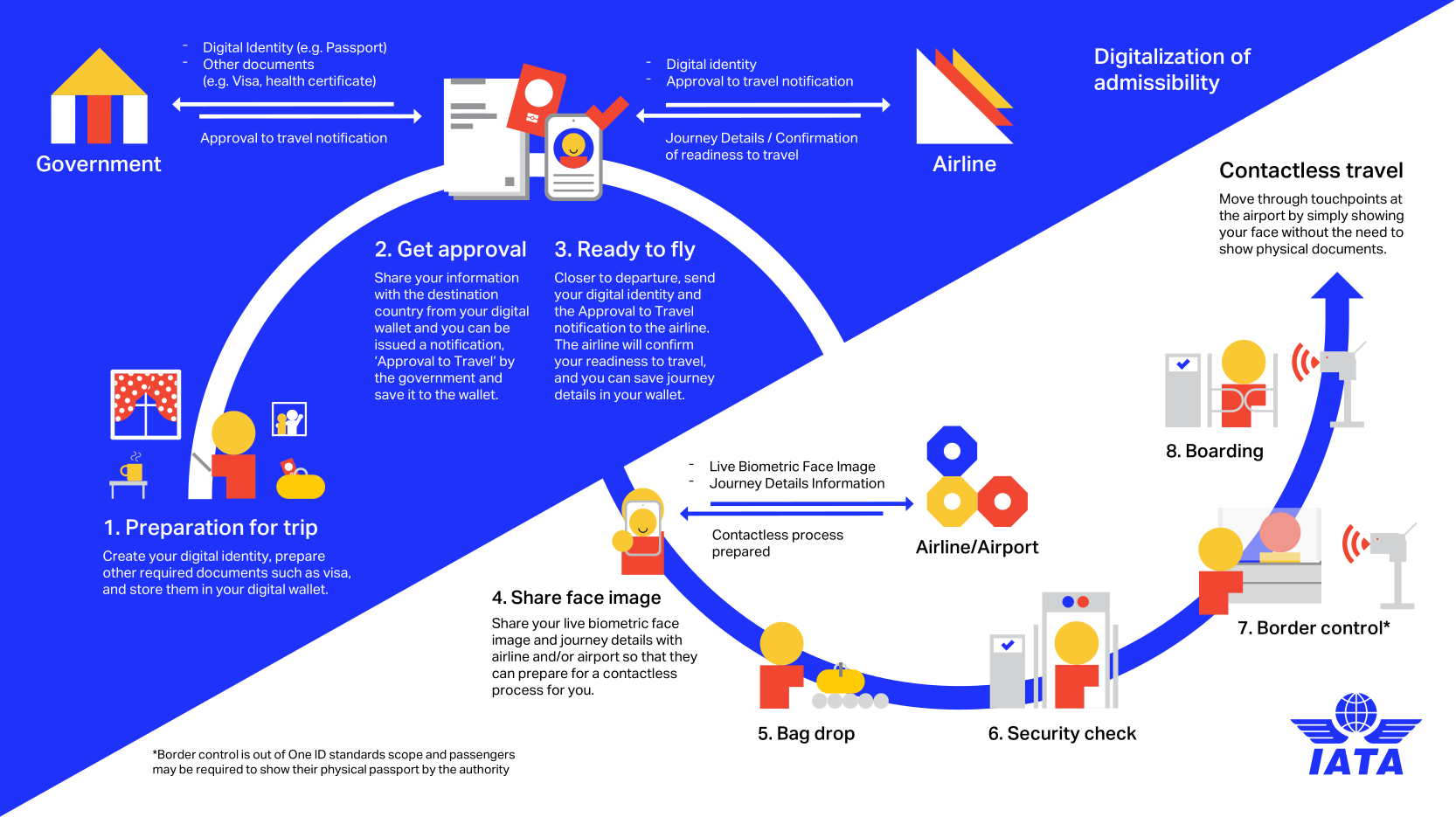

The International Air Transport Association (IATA), the global airline trade association and lobbying group, envisions a common-use shared public-private infrastructure of data exchange and facial recognition that will enable both individualized, permission-based control by destination governments of who can board flights at foreign airports, and business process automation and passenger tracking by airlines and airports:

Human rights have no place in IATA’s vision any more than nin lCAO’s egal analysis. Airlines and governments take for granted that boading a flight requires “approval to travel” from the government of the destination country. Airlines and governments alike will continue to act on this human-rights-disrespecting assumption unless and until it is called into question and they are forced to change their practices.

The Special Rapporteur’s analysis of the illegality of denial of boarding or requirements for permission from a destination country’s government before departing from a country of origin is in line with the arguments we made in our submission to the U.N. Office of the High Commisisoner for Human Rights in its most recent consultation on the human rights of migrants, and in our responses to the pending prposals by US Customs and Border Protection to expand its collection of API data and to require Advance Travel Authorization prior to departure from other countries.

Crucially, the Special Rapporteur recognizes that “the possibility of future denial of admission is not a lawful basis for a prospective denial of the right to leave any other country.” The Special Rapporteur’s analysis of this point is so fundamental, and has been so completely disregarded, as to be worth quoting at length:

It is crucial to emphasize that the right to leave a country is separate and independent from any question about eligibility to enter another country. While the rise of international API and PNR data sharing has allowed for efficient communication between States, it is important to resist the conflation of the concepts of exit, movement, and entry, and the legal regimes governing those concepts. As a matter of law, State A is not entitled, save in exceptional circumstances, including, for instance, the arrest of criminal suspects, to prevent persons from exiting State A. Nor is State B save in exceptional circumstances entitled to prevent persons from exiting State A, even if State B may be entitled to prevent persons from entering State B upon arrival (subject to its obligations to respect the right of would-be entrants to seek asylum). That is why Article 13 of the Chicago Convention provides that administrative requirements that a State party apply only ‘upon entrance into or departure from, or while within the territory of that State’154 and not also upon departure from a third State for a journey to the State party.

This is not merely a point of academic interest. The reason why the asylum claims must be determined upon arrival rather than prior to departure is not because of purist adherence to legal technicality – it is because a prospective applicant for asylum may be free to disclose and explain their situation in full only once outside the jurisdiction of the State from which they seek to flee. Facts caught by API data and/or PNR data collection and analysis and which might be flagged as worthy of concern in the abstract include: (a) apparent inconsistencies in official identification documents; (b) an unexplained source of funds for travel; (c) transfers of money from overseas being used to fund travel; and (d) disjunct between travel behaviour and family connections.

But such factors could very well be related to legitimate reasons for clandestine travel for the purposes of seeking asylum or fleeing domestic abuse or threats of violence. Unconventional behaviour regarding travel for such purposes, if presented and considered

by border officials in person upon arrival, could form the basis for meritorious asylum applications or discretionary grants of entry on humanitarian grounds according to relevant national legislation in line with international standards. The blanket use of a system whereby automatic decisions are made as to eligibility to disembark prior to departure prevents any such discretionary apparatus functioning as it should. Accordingly, programming which supports the use of API and PNR data in pre-departure screening

decisions poses a real risk of frustrating legitimate exercise of free movement and associated rights.Of course, if would-be entrants are found, upon assessment, not to have good grounds for an asylum claim, the State of arrival is entitled, under international law, to deport them (subject to the prohibition on refoulement contained in the Refugee Convention). But the possibility of future denial of admission is not a lawful basis for a prospective denial of the right to leave any other country.

While the Special Rapporteur’s report focuses primarily on the role of the U.N. Countering Terrist Travel program, it also calls out the role of ICAO as a U.N.-affiliated treaty body and the binding character of ICAO standards.

Reconstruction of ICAO decision-making and standards to incorporate the missing recognition of human rights will require involvement of U.N. bodies with human rights mandates, including the office of the Special Rapporteur, as well as human rights NGOs that have not, to date, been included in ICAO working groups, consultations, or decision-making. This is unlikley to happen unless human rights groups and the Special Rapportuer engagement with ICAO one of their priorities.In the year since the previous Special Rapporteur’s report, despite reminders of the importance of the issue from her successor, there has been no “pause” in the globalization of government access, use, and sharing of airline reservation data. There has boon no more thorough review of the implications of these schemes for human rights, including the right to freedom of movment and the right to asylum. There has been no reframing of desision-making about these schemes to put human rights first. But that doesn’t mean that the Special Rapporteur’s report on travel and human rights should be forgotten. The issues it raises will remain a priority for our human rights activism.

Pingback: UK “Electronic Travel Authorization” sets a bad example – Papers, Please!

Pingback: Surveillance as a service (SAAS) – Papers, Please!