The airport of the future is the airport of today — and that’s not good.

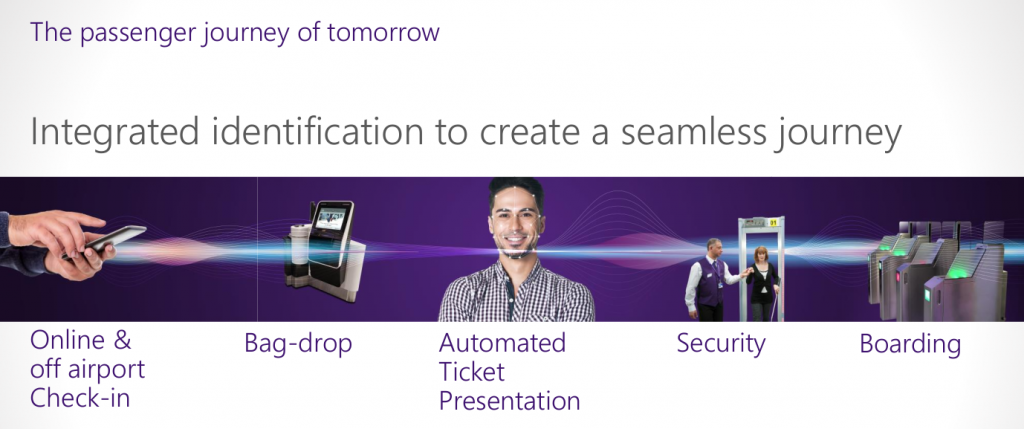

[Facial recognition at each step in airline passenger processing. Slide from presentation by Heathrow Airport Holdings Ltd. to the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) Traveler Identitification Program symposium, October 2018]

[Facial recognition at each step in airline passenger processing. Slide from presentation by Heathrow Airport Holdings Ltd. to the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) Traveler Identitification Program symposium, October 2018]

Today, the day before Thanksgiving, will probably be the busiest day for air travel in the USA since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020.

If you are flying this week for the first time in three years, what will you see that has changed?

Unfortunately, many of the most significant changes made during the pandemic are deliberately invisible — which is part of what makes them so evil.

During the pandemic, largely unnoticed, the dystopian surveillance-by design airport of the future that we’ve been worried and warning about for many years has become, in many places, the airport of today.

While travelers were sheltering in place during the COVID-19 pandemic, airports have taken advantage of the opportunity to move ahead with expansion and renovation projects. While passenger traffic was reduced, and terminals and other airport facilities were operating well below capacity, disruptions due to construction could be minimized.

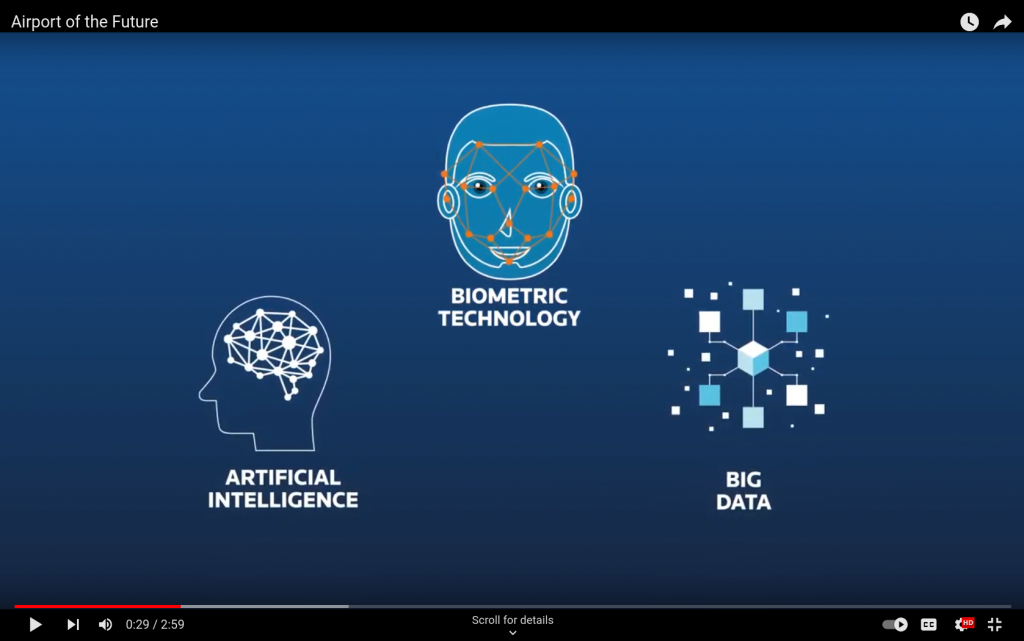

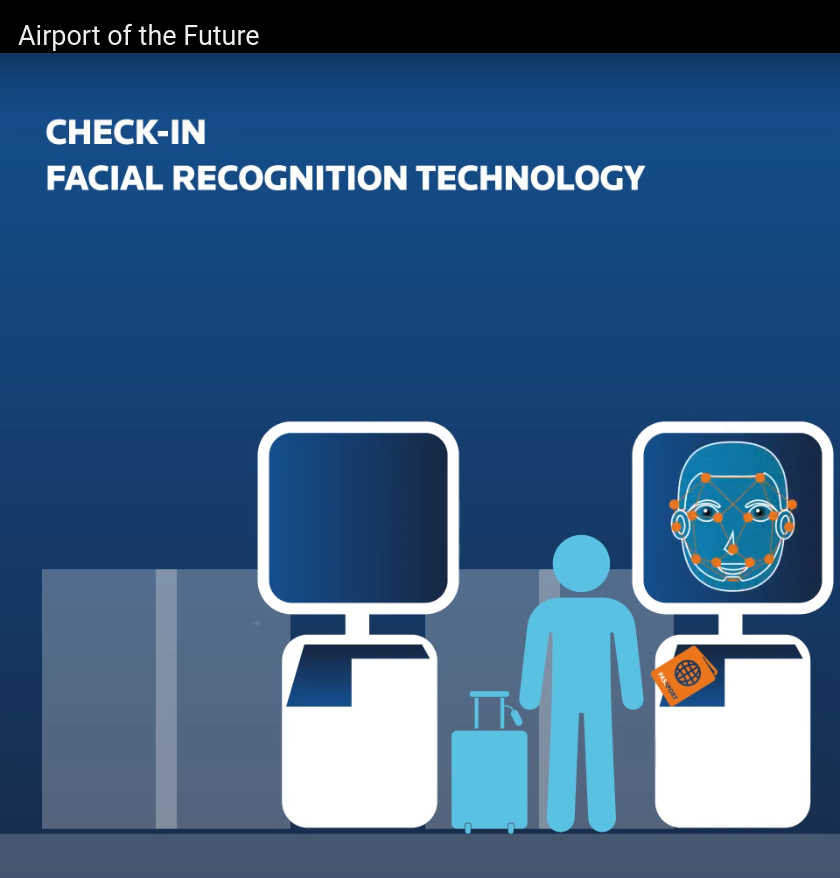

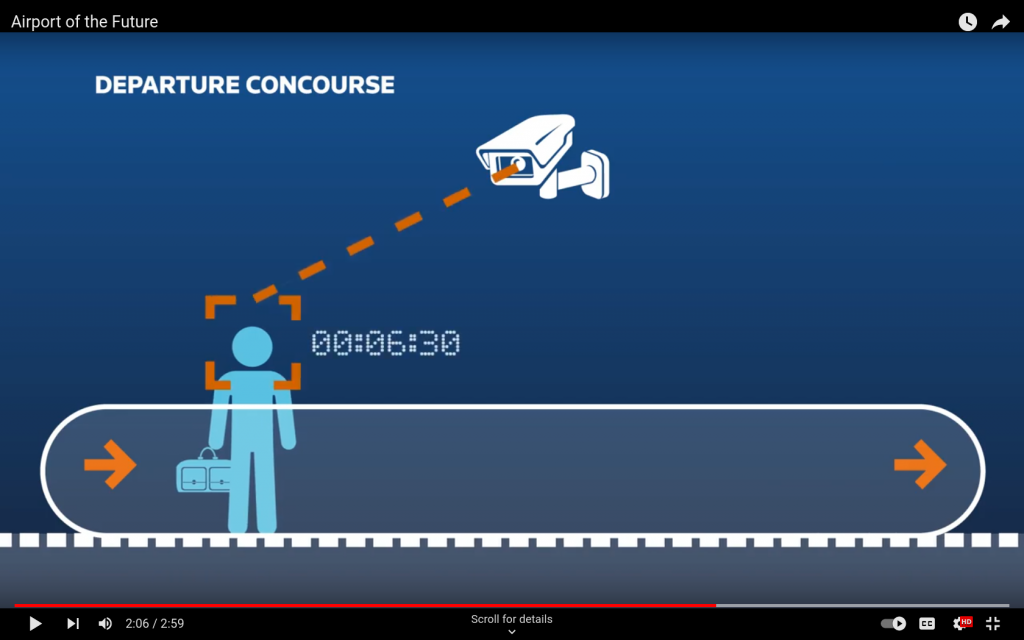

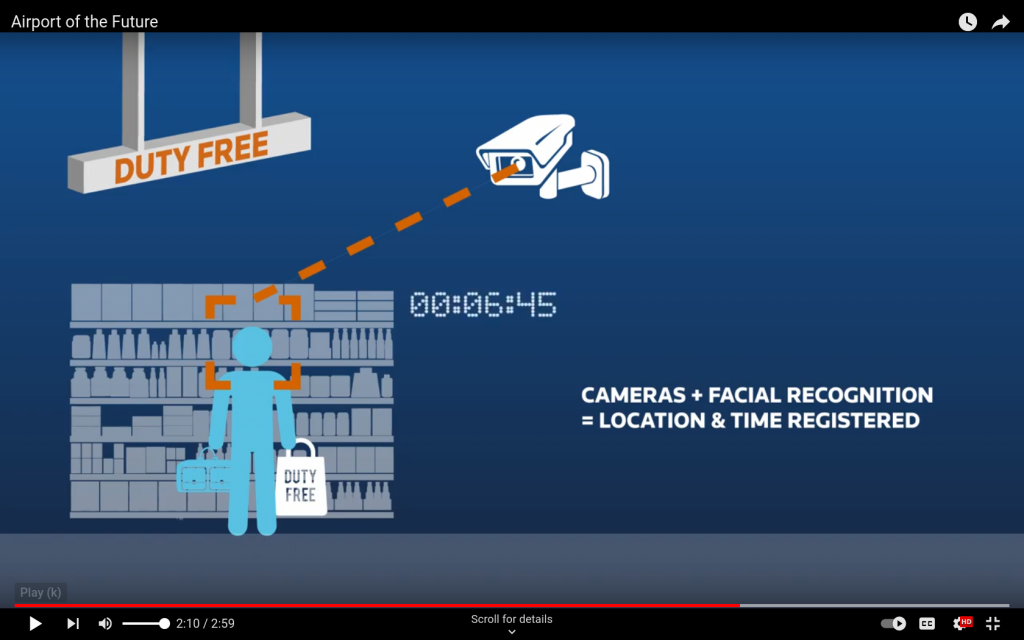

A characteristic feature of almost all new or newly-renovated major airports in the U.S. and around the world is that they are designed and built on the assumption that all passengers’ movements within the airport will be tracked at all times, and that all phases of “passenger processing” will be carried out automatically using facial recognition, as shown in this video from a technology vendor, Airport of the Future:

[Stills from 2019 vendor video, Airport of the Future.]

[Stills from 2019 vendor video, Airport of the Future.]

In the airport of the future, or in a growing number of present-day airports, there’s no need for a government agency or airline that wants to use facial recognition to install cameras or data links for that purpose. As in the new International Arrivals Facility at Sea-Tac Airport, which opened this year, the cameras and connectivity are built into the facility as “common-use” public-private infrastructure shared by airlines, government agencies, and the operator of the airport — whether that’s a public agency (as with almost all U.S. airports) or a private company (as with many foreign airports).

This integrated and as-invisible-as-possible surveillance infrastructure exemplifies the malign convergence of interests between government agencies that want to identify and track travelers for pre-crime predictive profiling and control, and airlines and airports (motivated by “business efficiency” even when they are operated by instrumentalities of state and local governments) that want to use the same hardware, and data from government ID databases, for business process automation and revenue maximization.

That malign convergence of interests extends to an interest in making surveillance tech inconspicuous and, if it is visible at all, making it appear “normal” and unavoidable. Neither government agencies nor travel companies nor airports want travelers to notice or question what is happening, or want to take responsibility for it. If travelers ask questions, airlines want to be able to answer, “the Federal government made us do it”, even if that isn’t true (as it unquestionably isn’t for U.S. citizens or any domestic flyers within the U.S.).

The integration of facial recognition into the airport structure makes these surveillance systems and practices much less visible — by design — than retrofitted or standalone surveillance cameras. Their positioning along the flow of passengers from airport entrance to aircraft door makes it almost impossible to pass through the airport and board a plane without being photographed, identified, and tracked.

“Opting out” is, in these new airports and terminals, a largely theoretical option available only to those travelers who already know their rights (without being given notice of them), who figure out how to assert them (again without notice), and who are willing to put up with additional questioning, search, and/or delay.

The TSA plans to extend this model to all domestic as well as international flights. But Congress has mandated collection of some biometric data (although not necessarily facial images) only from foreign-citizen non-resident visitors entering and exiting the U.S. There is no legal basis for requiring U.S. citizens (even those traveling internationally) or domestic travelers to submit to mug shots as a condition of air travel. As a result, universal facial recognition at U.S. airports is being deployed first on international flights.

To use the example of flights between the U.S. and the U.K., here’s how this looked to technology journalist Wendy M. Grossman (a U.S. citizen not subject to any U.S. legal mandate for “biometric exit” controls) on a recent flight from Chicago to London:

“What’s that for?” I asked. The question referred to a large screen in front of me, with my newly-captured photograph in the bottom corner. Where was the camera? In the picture, I was trying to spot it.

The British Airways gate attendant at Chicago’s O’Hare airport tapped the screen and a big green checkmark appeared.

“Customs.” That was all the explanation she offered. It had all happened so fast there was no opportunity to object.

Behind me was an unforgiving line of people waiting to board. Was this a good time to stop to ask:

- What is the specific purpose of collecting my image?

- What legal basis do you have for collecting it?

- Who will be storing the data?

- How long will they keep it?

- Who will they share it with?

- Who is the vendor that makes this system and what are its capabilities?

It was not.

I boarded, tamely, rather than argue with a gate attendant who certainly didn’t make the decision to install the system and was unlikely to know much about its details.

As we’ve seen recently ourselves, there’s just as little transparency at the airport about the facial recognition systems in use on flights in the opposite direction, from the U.K. to the U.S.. And the trend is toward making the facial recognition systems less visible and harder to avoid.

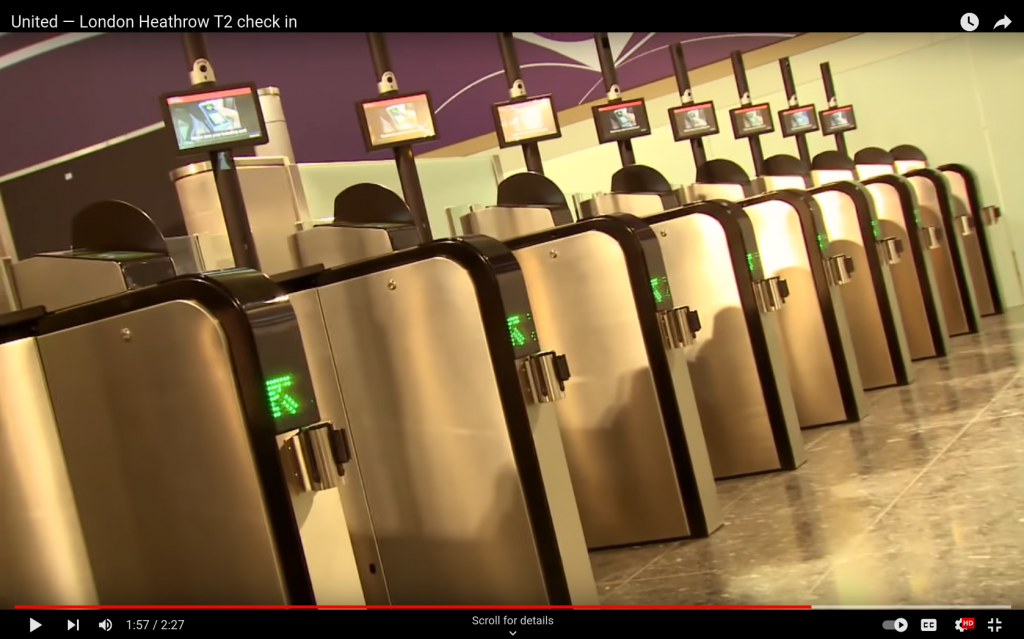

Since Heathrow Airport’s newest terminal opened in 2014, all passengers en route through Terminal 2 from the check-in area to the shopping-and-waiting area and departure gates have been required to pass through a corridor blocked off by a row of dividers, each of which contains a boarding-pass scanner.

In the absence of any signage as to the purpose of this checkpoint, the implication is that this is some sort of “Ticketed passengers only beyond this point” control.

When Terminal 2 opened in 2014, there were cameras in the vertical stanchions between each lane, in a contrasting silver-against-black band just above each display screen, as seen in this walk-through video posted at that time to YouTube by United Airlines:

The cameras weren’t exactly conspicuous, although they were visible, and the only message on the display was, as it still is today, “Please scan your boarding card”:

There was nothing on the display like, “Look at the camera.” There was no notice about cameras or automated facial recognition. You’d have been unlikely to notice these cameras if you were looking down at your hand to position your boarding pass on the scanner. The lanes were unattended. There was no apparent way to get through the checkpoint while avoiding being photographed. But at least in this first iteration, there was some chance that passengers might notice the cameras.

Today, things have gotten worse. A slide from a 2018 presentation to the Airports Council International by the manager of Heathrow’s automation program shows something more like what this checkpoint looks like today, with no cameras visible on the stanchions:

There’s still no signage about cameras or facial recognition. On a recent trip through this terminal, we looked for cameras at this checkpoint, but didn’t see any. But there are still cameras somewhere, focused on each lane. Perhaps they are better hidden in the stanchions, the boarding-pass scanner itself, or the ceiling.

Only the small percentage of travelers still wearing face masks — the travelers whose faces can’t be photographed because they are covered — receive any clue that the airport is trying to photograph them. If you are wearing a mask, after you scan your boarding pass the display changes to “Please remove your face mask“. But there’s no explanation of what’s happening or why, no staff at the boarding-pass scanners to ask, and no obvious way to opt out.

Heathrow Airport is operated by a private company, Heathrow Airport Holdings Ltd. The company’s privacy notice says it collects information including, but not limited to, “biometrics”, and that, “We are governed by regulations from the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) and Department for Transport (DfT). In order to comply with these regulations, we need to collect and process the above personal data relating to you and your flight.”

As is typical of airports in the U.S. and other countries, the airport operator thus claims that its collection of biometrics is required by law, even though Heathrow Airport Holdings Ltd. has been among the most enthusiastic voluntary collaborators with government agencies in biometric surveillance.

In response to a subject access request after our flight, Heathrow’s Data Protection Office told us that, “We can confirm that there are biometric cameras linked to these gates, but they are only used for passengers who are travelling domestically or to Ireland. As this is not applicable to you, no biometric images were taken.”

If this were what were actually happening, and with proper notice, it would be consistent with U.K. law, which requires collection of biometrics only for flights within the British Isles. But if biometrics are only collected from passengers ticketed to points within the U.K. and Ireland, why does the display at the checkpoint flash “Please remove your face mask” after a masked passenger has scanned a boarding pass showing that they are ticketed to some other destination, such as the U.S.? Heathrow’s claim doesn’t pass the smell test.

The only plausible explanation is that facial images of all passengers are (illegally and without notice or a basis under U.K. law) being collected for purposes and uses that remain unknown. Heathrow’s Data Protection Office claims that, “no information which is collected by these gates are passed onto United Airlines,” but even if that claim is true, it begs the question of whether photos or other data are passed on, directly or indirectly, to the U.K. government, the U.S. government, or other third parties.

Is this legal under U.K. law? Heathrow submitted its biometric passenger processing plans to the U.K. Information Commissioner’s Office in 2020 as one of the first participants in the ICO’s Regulatory Sandbox for advance review of new services that implicate personal data. The ICO’s final report recommended that Heathrow obtain “explicit consent” for collection of biometrics. The ICO report didn’t specify how this was to be done, and on our recent trip through Heathrow we were never asked for consent for collection of our biometrics.

The ICO report also noted that, “The ICO also advised that, provided that the passengers had a sufficient opt out opportunity while they were still in the UK, consent gathered by Heathrow on the behalf of the Airlines for purposes of ensuring that the international transfer of personal data to CBP in the United States was compliant with Article 44 of the GDPR, would likely be considered valid.”

This seems to contradict the claim that biometrics were to be collected by Heathrow solely for passengers on flights within the British Isles, not flights to the U.S. Why would data about passengers on domestic U.K. flights or flights to Ireland be passed to U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP)? Or is Heathrow, contrary to its claims, really collecting biometrics on all passengers, and sharing data about those bound for the U.S. with CBP? Anyway, the ICO’s prospective approval rested on explicit consent. Heathrow never asked for our consent to collect any information at all, much less to transfer any information about us to CBP.

We’re still waiting for the response to our subject access request to Heathrow Airport Holdings Ltd.

Things went badly before we boarded our flight in London. They got worse when we arrived in the USA.

Up through our last trip abroad, just before the COVID-19 pandemic, we have always been allowed, as U.S. citizens, to opt out of being photographed by CBP.

We’ve been questioned about why we aren’t standing in front of the camera at the CBP inspection station (“I don’t want to be photographed”) and why we don’t want to be photographed (“I don’t see a Paperwork Reduction Act notice saying it’s required”).

We’ve been told by a CBP inspector that in the future, the cameras will be mounted in the ceiling and we’ll be photographed before we get to the inspection counter, like it or not. That probably accurately repeats what front-line CBP staff have been told, although it contradicts what high-level CBP officials have claimed to us and other civil rights activists.

But after that brief questioning, CBP inspectors have always allowed us to proceed without further threats or harassment, and (so far as we can tell) without any black marks being recorded against us in in our permanent file in CBP’s Automated Targeting System.

Whether because things have changed since the pandemic, or because of our bad luck in which airport we arrived at (Logan Airport in Boston) or which CBP inspector we ended up in front of, we got a different reception on our most recent arrival in the U.S.

The CBP inspector at Logan Airport last month first grilled us with a series of leading questions about why we didn’t want to be photographed. “Don’t you know that we already have your photograph?” We got the impression that perhaps they would be marked down in their performance score if they didn’t persuade us to consent to mug shots and facial recognition.

When we politely repeated that we didn’t consent to be photographed, they made us wait while they created an incident report in the TECS and ATS systems, as though we had been selected for secondary screening. The CBP official in charge of the ageny’s facial recognition program told a reporter last month that “The numbers of people who opt out, it’s negligible. It’s not even something that we measure.” But as we discovered empirically, that’s a lie: A permanent record of our out-out was entered in the ATS file about us.

You can see some examples of ATS records in these slides from a presentation we gave in 2013 based on CBP responses to Privacy Act and Freedom Of Information Act requests for ATS and TECS records. The record that on this date in 2022 we opted out of facial recognition on arrival in the U.S. — as was our right — will now be retained and used as one of the inputs to the pre-crime predictive black box that decides how intrusively to interrogate and search us, and whether to allow us to fly at all, for the rest of our life.

If opting out of facial recognition is our right as a U.S. citizen, why should it be the basis for an entry in our permanent file?

The CBP inspector at Logan also demanded that we show them our boarding pass. We had already boarded, eight hours earlier in London. We had no further need of our boarding pass. We know of no law requiring a traveler to retain their boarding pass after boarding, or after completion of their flight, to show to CBP or for any other purpose. Normally, we shred our boarding passes at the first opportunity, to prevent it from being used by stalkers, burglars, or other malign actors to access our reservations. But the CBP inspector was insistent. We don’t know what would have happened if we hadn’t eventually found and handed over our boarding pass.

Presumably, CBP’s reason for wanting our boarding pass was to obtain the record locator for our Passenger Name Record (PNR) with the airline. The record locator is the same data a hacker or identity thief would want, and which makes a boarding pass so sensitive. By confirming the record locator they had already received as part of an Advance Passenger Information (API) transmission from the airline, CBP could more definitively link the traveler who had opted out of facial recognition with the rest of the data in their PNR.

When we asked what was happening, the CBP inspector at Logan told us, “They’ll explain everything downstairs.” That sounded ominous, but perhaps it was just another intimidation tactic to get us to consent to facial recognition. When we got downstairs to claim our baggage after the immigration inspection, we left though the green “Nothing To Declare” lane without further questioning or any search at all of our luggage.

Despite numerous unanswered questions about what’s going on behind the scenes, it seems likely that what happened to us in London and Boston is a taste of things to come: (1) increasingly unavoidable and invisible (or at least undisclosed and as unobtrusive as technology permits) facial imaging and image-based tracking of all air travelers, and (2) increasingly intrusive and delaying disfavored spot treatment and permanent suspicion of travelers who seek to opt out of biometric surveillance.

Welcome to the airport of the future, today.

[Soundtrack: Bill Steele, The Walls Have Ears, as performed by Wendy M. Grossman for the Big Brother Awards, 2004. Just imagine that it’s been changed to, “The Walls Have Eyes”.]

Pingback: Links 24/11/2022: OBS Studio 29.0 Beta | Techrights

Online discussion of this topic with Edward Hasbrouck (The Identity Project), Prof. David Farber (Keio Univ. Cyber Civilization Research Center), and Prof. Dan Gillmor (Arizona State Univ.), CCRC / IP-ASIA weekly online gathering on current issues, Monday, Nov. 28, 2022, 9 p.m. JST / 4 a.m. PST / 7 a.m. EST: https://ip.topicbox.com/groups/ip/T0a3e3d69334e792a/ccrc-ip-asia-nov-28-9-pm-jst-the-airport-of-the-future-edward-hasbrouck

Pingback: How To Keep Economy Passengers Out Of Business Class Bathrooms [Roundup] - View from the Wing

Keio University CCRC / IP-Asia presentation: “The Airport of the Future Is the Airport of Today” (20 min.):

Streaming video: https://vimeo.com/783990038

Invitation: https://ip.topicbox.com/groups/ip/T0a3e3d69334e792a

Slides: https://hasbrouck.org/articles/Hasbrouck-IP-Asia-28NOV2022.pdf

Download podcast audio (listen with slides: https://hasbrouck.org/audio/Hasbrouck-airport-audio-28NOV2022.mp4

Download video (includes slides): https://hasbrouck.org/video/Hasbrouck-airport-video-28NOV2022.mp4

Privacy News, December 2, 2022: Travel privacy:

https://privacy.thenexus.today/privacy-news-december-2/

Pingback: TSA confirms plans to mandate mug shots for domestic air travel – Papers, Please!

Pingback: TSA confirms plans to mandate mug shots for domestic air travel - neweu

Pingback: Opting out of facial recognition at airports - The Power Hour

Pingback: What will the future bring for ID demands? – Papers, Please!

Pingback: CBP facial recognition is a service for the airline industry – Papers, Please!

Pingback: Human Rights and “Countering Terrorist Travel” – Papers, Please!