Do you think that if you are a U.S. citizen you have a right to return to your country, and don’t need “authorization” from the US government?

Article 12, section 4 of the ICCPR (a treaty ratified by and binding on the US) provides that “No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of the right to enter his own country.” And the right of US citizens to enter the US has long been recognized as one of the most fundamental aspects of the Constitutional right to travel.

But it appears that’s not what the US government thinks:

[Click image for larger version.]

[Click image for larger version.]

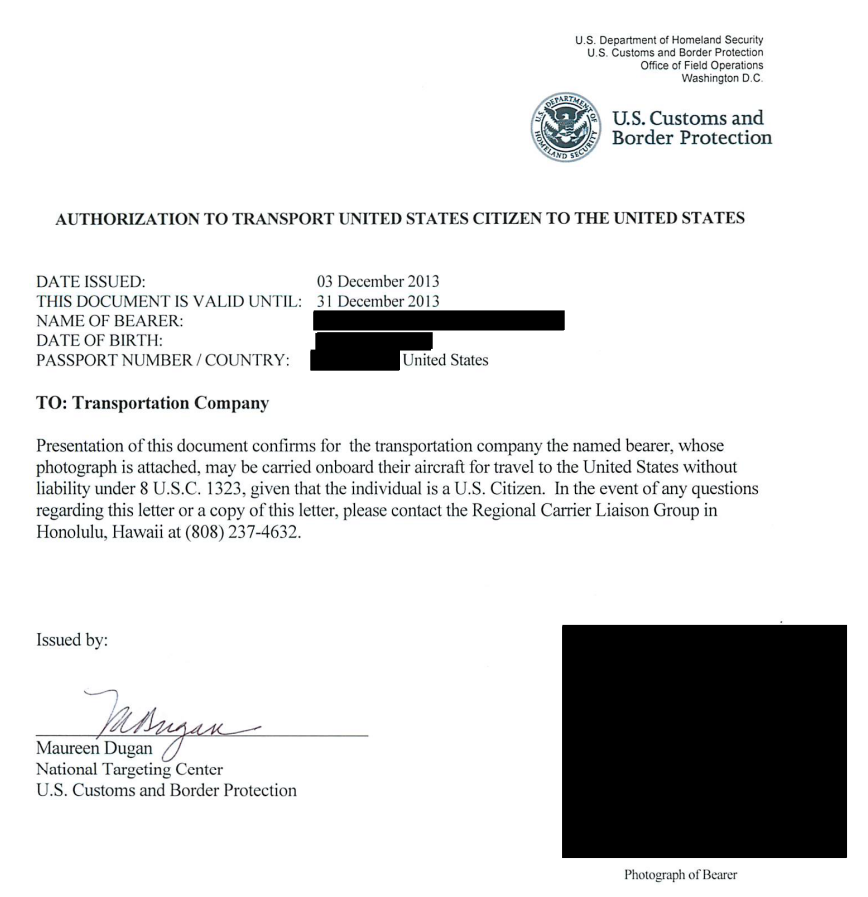

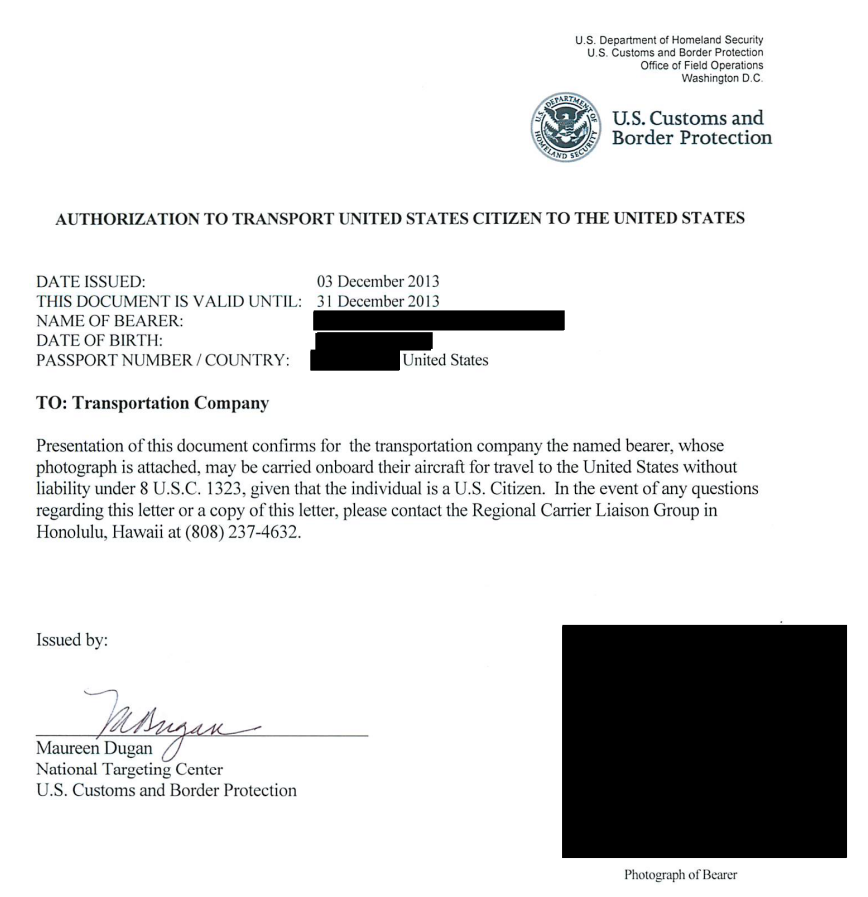

This bizarre “yes-fly” document, first made public today and first published here, was provided to lawyers for Dr. Rahinah Ibrahim on the fourth day of the week-long trial last month of Dr. Ibrahim’s lawsuit challenging her placement on the US government’s “no-fly” list.

The day before the trial began, Dr. Ibrahim’s US-born US-citizen daughter, Ms. Raihan Mustafa Kamal, was denied boarding on the first of a set of connecting flights she had booked from Malaysia to to San Francisco to attend and testify at her mother’s trial.

Lawyers for the government defendants, including US Customs and Border Protection (CBP), claimed that they had “confirmed that the defendants did nothing to deny plaintiff’s daughter boarding…. she just simply missed her flight. She has been re-booked on a flight tomorrow. She should arrive tomorrow.”

As it turned out, none of those claims were true. Ms. Mustafa Kamal hadn’t “missed” her flight. She showed up on time, but , but was denied boarding as a result of an email message from CBP to the airline. She wasn’t booked on any other flight, and she never made it to her mother’s trial.

At a hearing held the afternoon after the rest of the trial had concluded, Dr. Ibrahim’s lawyers presented a sworn declaration from Ms. Mustafa Mamal including a copy provided to her by Malaysia Airlines of the email message from CBP that led to her being denied boarding.

In response to Judge Alsup’s demands (“I want a witness from Homeland Security who can testify to what has happened. You find a witness and get them here…. I want to know whether the government did something to obstruct a witness”), the defendants brought the director of the CBP’s National Targeting Center, Ms. Maureen Dugan, to San Francisco to testify and face cross-examination about what had happened to Ms. Mustafa Kamal. At the defendants’ insistence, however, the courtroom was cleared of spectators for all of Ms. Dugan’s testimony and the remainder of that hearing.

The defendants also filed a declaration from Ms. Dugan. That declaration was filed “under seal”, but after his verdict Judge Alsup reiterated his order that a summary or redacted version of each sealed document, specifically including Ms. Dugan’s declaration, be made public.

Today the government defendants filed a redacted version pf Ms. Dugan’s declaration about what happened to Ms. Mustafa Kamal, including the “AUTHORIZATION TO TRANSPORT UNITED STATES CITIZEN TO THE UNITED STATES” reproduced above.

So now, as a result of this case and specifically as a result of CBP’s misconduct with respect to Ms. Mustafa Kamal, we have seen for the first time both a no-fly message and a yes-fly message.

What can we learn from these strange goings-on and communications?

The US government seems to think that even US citizens need the government’s permission to travel to the US. The CBP didn’t issue a reminder to airlines or other common carriers of their general obligation to transport all qualified would-be passengers, or sanction the airline for denying boarding to Ms. Mustafa Kamal despite her undisputed US birth and US citizenship.

Rather, the CBP issued an individualized, time-limited authorization to airlines to transport Ms. Mustafa Kamal to the US. Such affirmative, individualized “authorization” would make no sense unless the default, even for a US citizen, is, “NO.”

This is a blatant violation of US citizens’ Constitutional rights, and of US obligations as a party to the ICCPR.

(A somewhat similar “Transportation [Authorization] Letter” is discussed on p. 46 of the CBP Carrier Information Guide for airlines. But the example shown in the Carrier Information Guide is for a non-US citizen whose “Green Card” has been lost, stolen, or damaged while they are abroad, and who needs temporary evidence of permanent US residency to be able to return to the US to get her Green Card replaced. A Green Card — US permanent residency document — can’t be replaced outside the US, but a passport can. So it’s unclear why a US citizen would need such a document in lieu of an emergency passport, or why it would be considered better evidence of US citizenship than a passport.)

But why did CBP send a “possible no-board request” with respect to Ms. Mustafa Kamal?

Was Ms. Mustafa Kamal, like her mother, “mistakenly” placed on the no-fly list? Dr. Ibrahim’s lawyer — who knows Dr. Ibrahim’s status on or off the no-fly list, but is not allowed to disclose this information to her client or to the public — stated in open court during closing arguments that Ms. Mustafa Kamal’s status on the “no-fly” list was “the same as that of her mother”. But it seems more likely, from the rest of what has been claimed publicly, that neither of them are currently on the no-fly list. If Ms. Mustafa Kamal were, in fact, on the no-fly list, it would have been an out-and-out lie for government lawyers to tell Judge Alsup that their client CBP was not responsible for the airline’s denial of boarding to Ms. Mustafa Kamal.

A more likely explanation is that Ms. Mustafa Kamal and her mother are currently both on what was described euphemistically in pleadings made public in redacted form yesterday as a “watchlist”, but which is used in a manner that results in it functioning as a de facto blacklist with the same effect as the “no-fly” list. The email message sent to the airline didn’t say anything explicit about the no-fly list, but its natural and foreseeable consequence was that Ms. Mustafa Kamal would be denied boarding — as in fact she was.

Perhaps most disturbingly, this suggests that the government could nominally comply with Judge Alsup’s order to remove Dr. Ibrahim from the “no-fly” list, but keep her on a “watchlist” that has the same effect.

Only if Dr. Ibrahim gets a US visa (which seems unlikely) and tries to travel to the US, or if she tries to fly on a US-flag carrier (such as on United Airlines from Singapore to Hong Kong or Tokyo), or if Ms. Mustafa Kamal tries again to travel to the US, are we likely to learn more about what actual US government actions and restrictions either of them is subjected to. That, and not the label placed on any list, is what matters.