“No-fly” trial, day 5, part 2: What happened to the plaintiff’s daughter?

“Your Honor, we’ve confirmed that the defendants did nothing to deny plaintiff’s daughter boarding. It’s our understanding that she just simply missed her flight.”

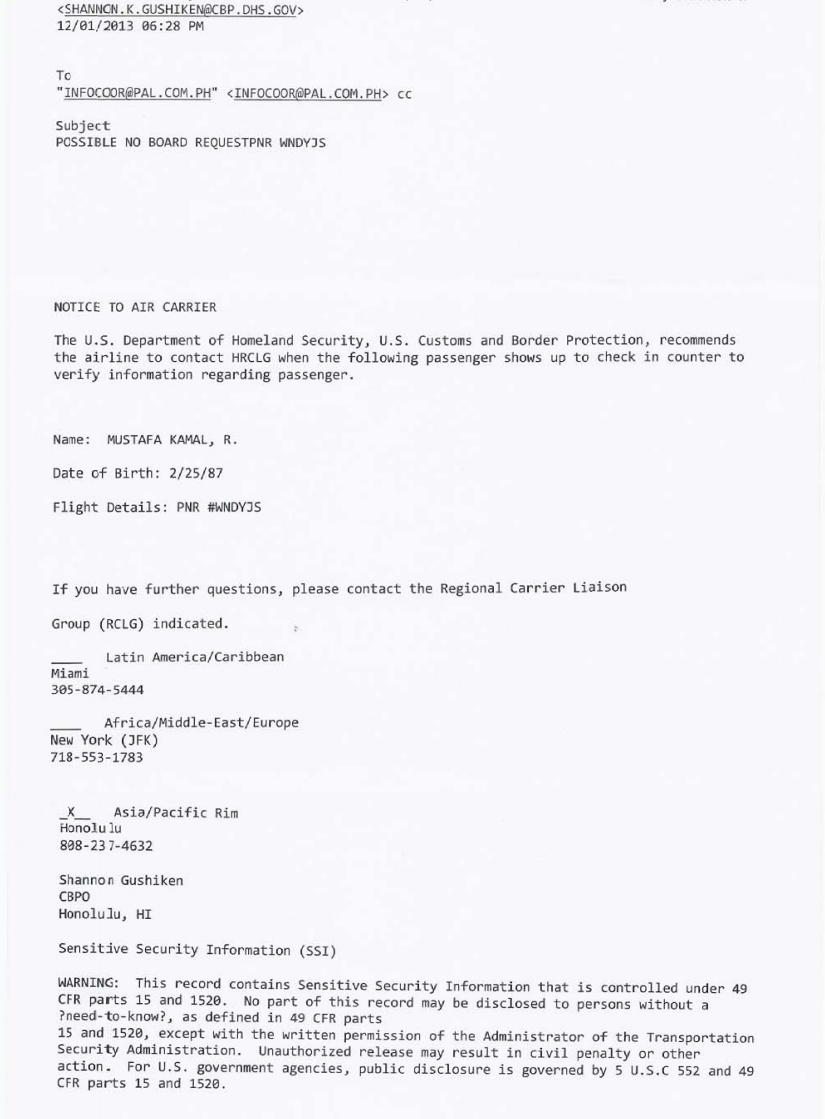

Neither the public, nor Dr. Rahinah Ibrahim, nor her daughter, Seattle-born U.S. citizen Raihan binti Mustafa Kamal, yet know why a U.S. Customs and Border Protection Officer sent the email message excerpted above to the airline on which Ms. Mustafa Kamal was scheduled to fly to San Francisco last Sunday to testify at the trial in Dr. Ibrahim’s lawsuit challenging her placement on the U.S. no-fly list. (Click the image for a larger version or here for the complete e-mail forwarding thread.)

We do know, however, that whatever happened when Ms. Mustafa Kamal showed up at Kuala Lumpur International Airport (KUL) two hours and 45 minutes before the scheduled departure of her flight and tried to check in, it certainly wasn’t (and CBP’s lawyers in San Francisco certainly couldn’t later have “confirmed”, as they claimed to the court on Monday), that Ms. Mustafa Kamal “just simply missed her flight”.

Friday afternoon, after what was to have been the conclusion of the trial in Ibrahim v. DHS, Judge William Alsup held an evidentiary hearing and heard argument from lawyers for Dr. Ibrahim and the government regarding what happened to Ms. Mustafa Kamal and what (if anything) he should do about it.

(See our separate article about the morning session, including the possibility of bar complaints against some of the government’s lawyers and a history lecture from Judge Alsup to the government about the blacklisting of Robert Oppenheimer on the basis of secret, false, allegations that he was a Communist: “No-fly” trial, day 5, part 1: Closing arguments.)

At the insistence of the government and on the basis of a declaration submitted in advance by the one witness, and over objections by Dr. Ibrahim’s lawyers, the courtroom was cleared for almost the entirety of both the hearing and the argument. The only in-person witness, Ms. Maureen Dugan, Director of the “National Targeting Center” operated by the Customs and Border Protection (CBP) division of DHS in Reston, Virginia, was questioned only behind closed doors, and her additional written declaration was filed with the court under seal.

Dr. Ibrahim’s lawyers were unable to present her side of the story through in-person testimony, of course, since the U.S. government agencies which are the defendants in the case have prevented both Dr. Ibrahim and Ms. Mustafa Kamal from coming to the U.S. for the trial. But a sworn written declaration by Ms. Mustafa Kamal, including the email message from CBP that led to her being denied boarding when she tried to fly to San Francisco last Sunday for the trial, was filed in the public court docket.

Following the hearing, Dr. Ibrahim’s lead counsel, Elizabeth Pipkin, said that at the conclusion of the closed court session Judge Alsup ruled:

- That the parties could refer to the events, exhibits, and testimony related to Ms. Mustafa Kamal in their proposed findings of fact and conclusions of law in Dr. Ibrahim’s case, and

- That Dr. Ibrahim and her lawyers would be allowed until noon Monday, December 9th, to decide whether to move to re-open the case.

If the case is re-opened, the parties would be able to present new evidence, call new witnesses, and/or re-call witnesses including government witnesses whose original testimony might be contradicted and whose credibility might be impeached by what happened to Ms. Mustafa Kamal and what statements they made about it. Ms. Mustafa Kamal could even be called as a witness, if she could find the money for another airline ticket and make it to the U.S. (In her declaration, she says that her original ticket cost MYR5751, equivalent to US$1782, and she can’t afford another ticket at that price. It’s already peak season for trans-Pacific travel to and from SFO, and on many airlines seats are unavailable at any price until after New Years.)

Aside from seeing Ms. Dugan enter and leave the closed courtroom, and what Ms. Pipkin said afterward about Judge Alsup’s rulings, we don’t know what the government may have claimed to Judge Alsup.

But when read closely, the public filings from Ms. Mustafa Kamal raise extraordinary questions of whether CBP and DHS have:

- Misrepresented their operations in official statements including their most recent formal report to the European Union on how they use airline reservation data,

- Tried to secretly strip a person born in the U.S. of her citizenship through some secret administrative action or deem her “inadmissible” to the U.S. despite her U.S. citizenship, and/or

- Misled the airline about the basis for their no-board request, and manipulated the airline through those false pretenses into wrongly denying boarding to Ms. Mustafa Kamal despite the fact that she is a native-born U.S. citizen with an absolute, unconditional, and irrevocable entitlement to admission to the U.S.

The email message that led Malysia Airlines to deny boarding to Ms. Mustafa Kamal was sent from the “@cbp.dhs.gov” email address of Shannon Gushiken, a CBP Officer (CBPO) at the CBP’s Asia/Pacific “Regional [Air] Carrier Liaison Group (RCLG) in Honolulu. It looks like a form letter, but it’s impossible to tell from the message itself whether there was any human involvement in sending it. It’s possible that it was auto-generated but that Ms. Gushiken or someone else had to press “send”, so that CBP could say that action wasn’t taken “solely” on the basis of automated profiling.

There are no direct flights from Malaysia to San Francisco. Ms. Mustafa Kamal was booked on Malaysian Airlines (IATA code MH) from KUL to Manila (MNL), connecting in MNL to a Philippine Airlines (PR) flight to SFO. The email message from CBP was sent to a functional address at PR, “INFOCOOR@PAL.COM.PH”, that being the airline on whose connecting flight Ms. Mustafa Kamal was scheduled to arrive in the U.S.

The message was forwarded to the ASD (“Aviation Security Director”?) for PR at their head office in MNL, who forwarded it to another ASD, who forwarded it to the PR office in Kuala Lumpur (SITA address “KULKZPR”). The “OIC” (“Officer in Charge” or station manager?) for PR in KUL forwarded it to several people with K.L. Airport Services (“@KLAS.COM.MY”), a contractor that handles passenger and ground handling operations for multiple airlines at KUL. Someone with KLAS gave a printout of the message to a Mr. Zainuddin, an MH supervisor who was summoned to the counter when Ms. Mustafa Kamal tried to check in.

The printout of the email given to Ms. Mustafa Kamal and filed with the court has a handwritten notation on the front page with the details of the flight on which she was booked (MH 802, 02 DEC, scheduled to depart (STD) 13:45 local time in KUL, which corresponds to 9:35 p.m. Sunday SFO time), and the record locator of her PNR in the MH reservation system (N2R79). Since the MH flight on which Ms. Mustafa Kamal was booked wasn’t destined for the U.S., MH wasn’t required to send CBP copies of PNRs or API data for this flight, and the email from CBP to PR gave only the record locator of the PNR in PR’s system for Ms. Mustafa Kamal’s reservation on the flight on which she was scheduled to arrive in the U.S. Presumably the MH details were noted on the printout by Mr. Zainuddin, one of his colleagues at MH, or someone with KLAS.

In deciding not to allow Ms. Mustafa Kamal to board the MH flight, Mr. Zainuddin was relying on an unverified printout of a four-times-forwarded email message that had been relayed through at least two independent commercial intermediaries, PR and KLAS, between CBP and MH, the airline that denied her boarding.

CBP would no doubt say, and perhaps did say in the declaration and/or in-person testimony it doesn’t want us to see, that (a) the system isn’t supposed to work quite like this, (b) CBP never ordered any airline not to allow Ms. Mustafa Kamal to board, and (c) the final decision was made by Malaysia Airline. If Ms. Mustafa Kamal was wrongly denied boarding by Malaysia Airlines, she can take up that matter in a Malaysian court, in a proceeding to which CBP will not be a party and in which it cannot be compelled to participate.

In fact, the system worked exactly the way it was supposed to: It is designed to allow CBP to act as puppet master, inducing airlines to act while evading ever being held accountable for, or being required to explain the reasons for, its “recommendations”.

As a common carrier, an airline has a legal duty to transport any passenger willing to pay the fare and comply with the terms and general conditions in its published tariff. In a case like this, the airline cannot defend itself on the grounds that it was “only following orders”, since the U.S. government’s position is that it didn’t issue any “orders” and that the airline made the no-board decision.

We’ve been through arguments with airlines that didn’t want to allow us to board because they suspected we wouldn’t be admitted to the country to which we wanted to fly. Sometimes they were right. If a passenger is denied admission, the airline can try to recover any consequential costs to the airline.

But if an otherwise-qualified passenger insists, the clear duty of an airline — under both their contract of carriage and the laws and aviation treaties pursuant to which they are licensed as a common carrier — is to transport that passenger, at her sole risk that she won’t be admitted. This right to common carrier transportation is, of course, of utmost importance for asylum seekers, but is vital for everyone. If an airline won’t transport you to a country of potential refuge, it doesn’t matter what right you might have to seek asylum there.

By inducing airlines not to transport would-be asylum seekers who the airline thinks won’t be admitted, as we said in one of our submissions to the U.N. Human Rights Committee, “the U.S. prevents legitimate asylum seekers from reaching the U.S., and turns unqualified airline check-in staff into de facto asylum judges of first and last resort.”

Legal niceties aside, though, what would you do if you were making the decision for an airline in a case like this?

Any airline which transports a non-U.S. citizen to the U.S. who on arrival is, for any reason, not admitted to the U.S., is strictly liable (pursuant to Section 273 of the Immigration and Naturalization Act) for an administrative fine of $3,000 per passenger plus costs of deportation.

Due diligence in screening passengers or attempting to verify whether passengers have valid documents or can anticipate being admitted (keeping in mind that, as the State Department’s officially designated witness testified in Dr. Ibrahim’s trial, a visa is merely “permission to approach the border of the U.S. or travel to a port of entry and ask for permission to enter,” not a permit to enter the U.S. or a guarantee of admission) can be considered in mitigation or for waiver of the fine, but does not relieve the airline of this strict liability. It’s inconceivable that the U.S. would waive the fine if the U.S. had recommended not boarding the person.

On the other side of the commercial scale, the chances that a would-be passenger denied boarding, especially in a foreign country, will find the right jurisdiction and the right basis to successfully prosecute a claim against the airline for violation of its contract of carriage are slight. We have yet to hear of such a case.

The only rational business decision, and the only decision that even an airline that wants to “do the right thing” can afford to take in the face of the extraordinary amounts of money that are collected daily from airlines in administrative fines for non-admission of passengers carried to the U.S., is to err on the side of denying boarding to anyone the U.S. government indicates it is likely not to admit.

But was the message sent by CBP related to whether Ms. Mustafa Kamal would be admitted to the U.S., if she could manage to make it to our shores, or to something else?

The message from the CBP that was passed on to Malaysia Airlines gave no indication of the basis for the “possible no board request” to which it referred. But it was sent from, and referred the airline to, the CBP “RCLG”.

What is the RCLG, and what is the scope of its mandate to send such messages?

As we’ve noted, permission-to-travel messages are sent to airlines electronically in the form of coded boarding pass printing results or instructions. The RCLGs are part of the out-of-band system — along with DHS personnel, some of them with diplomatic immunity, stationed at some foreign airports — used for additional communications between CBP and airlines when those messages don’t suffice.

There are three RCLGs for different world regions, generally corresponding to the three areas into which IATA (the international airline association) divides the world. The box for the Asia-Pacific RCLG in Honolulu was checked on the notice sent to Philippine Airlines about Ms. Mustafa Kama, but because that was the last of the three to be listed, and fell on the next page of the email printout, Mr. Zainuddin mistakenly referred Ms. Mustafa Kamal to the first RCLG on the list, the one for the Americas in Miami.

The RCLGs first came to public notice during the 2010 review by the European Union of U.S. compliance with the E.U./U.S. “agreement” on access to and use of PNR data transferred from the E.U. to the U.S. government:

[T]he Regional Carrier Liaison Group (RCLG) program should also be evaluated and audited as soon as possible. The standing of these programs needs to be explained and assessed.

In response to this E.U. report and recommendation, the DHS issued its first public statement about the scope of RCLG activities and decision-making. We commented on that statement when it was first leaked by Statewatch, as part of a larger critique of the misstatements in the U.S. report.

With respect to the RCLGs, the official 2010 DHS response to the E.U. report said:

The Regional Carrier Liaison Groups (RCLG) began in 2006 … to assist carriers with questions regarding U.S. admissibility-related matters. CBP officers assigned to the RCLG make recommendations to the carriers whether to board or to deny boarding to a passenger who would otherwise be inadmissible to the U.S. RCLGs are staffed solely by CBP officers…. [T]he CBP Officer assigned to the RCLG would communicate to the carrier based on API data to recommend that a passenger not be boarded because the individual would most likely be ineligible to enter the U.S., thus enabling the carrier to make a decision on whether to board the passenger. The final decision to board or not board lies with the carrier. [emphasis added]

That seems to make clear that RCLG recommendations were supposed to be related solely to potential eligibility for admission to the U.S., an immigration question which the government has argued throughout the trial in Ibrahim v. DHS is entirely independent of the no-fly list and eligibility for air transportation.

The 2011 Carrier Information Guide posted on the section of the CBP website for airlines similarly states the role of the RCLGs as being related to offering recommendations on “validity of documents or admissibility”, with no mention of no-fly lists or any other basis for RCLG recommendations:

Regional Carrier Liaison Groups (RCLG) have been created by CBP to assist carriers with questions regarding U.S. entry related matters, with a primary focus on assisting overseas carriers to determine the authenticity of travel documents. The RCLG will respond to carrier inquiries concerning the validity of travel documents presented or admissibility of travelers. Once a determination is made on validity of documents or admissibility, the RCLG will make a RECOMMENDATION whether to board the passenger or to deny boarding. The final decision to board or not board lies with the carrier. Regional Carrier Liaison Groups have been established in Miami, New York and Honolulu.

If you are unable to contact a nearby U.S. Embassy or Consulate representative, contact the RCLG servicing the embarkation point at the numbers listed below…. The RCLGs are available 24 hours a day, seven days a week. This service is available to all carriers worldwide for any flight destined to the United States.

The first joint report issued by the U.S. and E.U. concerning the PNR agreement (reports on previous reviews of the agreement were issued separately by the U.S. and E.U. teams), issued November 27, 2013, had this to say about the RCLGs:

Under the IAP, the role of DHS staff is to assist airlines and security personnel with document examination and traveller security assessment. The CBP liaison officers evaluate passengers selected by the targeters of the DHS National Targeting Center through further questions and assessment and, where appropriate, contact the airline for coordination. Eventually, the liaison officer will inform the air carrier if a passenger will be denied entry into the U.S. upon arrival and on this basis will recommend that the air carrier not carry this passenger on the aircraft. The IAP thus is intended to increase the number of travellers who are prevented from boarding an aircraft to the U.S., rather than permitting travellers to board but then deny them entry into the U.S. upon their arrival. This program concerns people who are not listed in the no-fly database…

The RCLG, implemented since 2010, basically is an extension of the IAP to locations where the U.S. does not have liaison officers at non-U.S. airports. Under the RCLG, which works otherwise in the same way as the IAP, the DHS National Targeting Centre makes direct contact with the carrier and recommends that it not carry the specific passenger, rather than having a CBP liaison officer making contact with the air carrier.

The IAP led in 2012 to 3600 global cases where travellers did not board a flight to the U.S. In the case of the RCLG, the number of global cases in 2012 amounted to 600 travellers, which brings the total number for 2012 under both programs to 4200 travellers. According to DHS, in most of the cases the inadmissibility is determined on the basis of the lack of a visa, or the use of a stolen or otherwise not valid passport. (pp. 6-7, emphasis added)

These statements were based on un-audited claims made by the DHS itself: “It has to be noted that the joint review is not an inspection of DHSs PNR policies and the EU team had no investigative powers.” (p. 3)

There’s no way to tell from the U.S./E.U. report how many of the people denied boarding as a result of RCLG recommendations were U.S. citizens like Ms. Mustafa Kamal. Indeed, there is no way that members of the E.U. review team receiving this information from the U.S. government, or anyone reading this report, would know that any of them could possibly have been U.S. citizens.

“Inadmissibility” to the U.S. cannot, by definition, apply to U.S. citizens. U.S. immigration authorities have no jurisdiction over, and U.S. immigration officers have no power to arrest, U.S. citizens. And the U.S. said clearly and explicitly in its formal report to the E.U., issued just days before the start of this trial, that RCLG recommendations are not concerned with people on the no-fly list (which might include U.S. citizens).

There appear to be only three possible explanations for these discrepancies, any of which is indicative of grave misconduct by the U.S. government in its adherence to the U.S. Constitution and its fulfillment of its international obligations:

- Ms. Mustafa Kamal is on the no-fly list, this formed all or part of the basis for the recommendation sent by the RCLG — and the U.S. lied to the E.U. about whether the RCLGs concern themselves with, and make recommendations with respect to, people on the no-fly list.

- Ms. Mustafa Kamal is not on the no-fly list — and the U.S. has secretly tried to strip her of her citizenship despite her having been born in the U.S., or has deemed her “inadmissible” to the U.S. despite her being a native-born U.S. citizen. This would be among the gravest and most direct possible violations of Ms. Mustafa Kamal’s rights as a citizen, of her human rights, and of U.S. obligations pursuant to Article 12 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. That wouldn’t be the first time this has happened, as we have reported to the U.N. Human Rights Committee. [The latest report, published this week, concerns the seizure of passports from hundreds of Yemeni-Americans by the U.S. Embassy in Sanaa, which we’ve been hearing about for several months form U.S. citizens trapped in Yemen.] But as the UNHRC said in its General Comment No. 27 on liberty of movement under Article 12 of the ICCPR, “In no case may a person be arbitrarily deprived of the right to enter his or her own country…. The Committee considers that there are few, if any, circumstances in which deprivation of the right to enter one’s own country could be reasonable. A State party must not, by stripping a person of nationality…, arbitrarily prevent this person from returning to his or her own country.”

- Ms. Mustafa Kamal is neither on the no-fly list nor inadmissible to the U.S. — but the U.S. sent a message calculated to be interpreted as indicating that she was inadmissible to the U.S. (since that is the only normal basis for such RCLG recommendations), and successfully misleading the airline into drawing that inference (which the U.S. knew to be false) and on that basis denying her boarding. This would have entailed an equally grave violation of Ms. Mustafa Kamal’s rights and U.S. obligations, compounded by the additional element of fraud perpetrated by the government against one of its own citizens.

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » “No-fly” trial, day 5, part 1: Closing arguments

First: thank you for your reporting on this trial. It’s a very important issue and I believe you’re doing it justice.

Second: “Out of band” not “out of bandwidth”

@ Brian – Thanks! Corrected.

Thank you so much for reporting this trial. I’m fascinated and horrified by what my government has done here, and shocked that it would defend these actions. Keep up your excellent work in shining a light on this travesty.

Thank you so very much for reporting this trail and the extraordinary lengths that the Ibrahins have had to endure to bring this issue to light. As a US Citizen, I am ashamed of the actions of the US Government. Tyranny looms unseen and unsuspected over us.

This trial should serve as a warning to all peoples, especially to Americans, that you too can be caught in the governments’ web of deceit and lies used to cover it’s unlawful actions.

We are rapidly approaching the time where decisions are to be made either for freedom or enslavement. I pray that all make the right choices when their personal moment of decision is upon them..

Slave-masters do not have the best interests of their slaves in mind.

You state in your Article that Ms. Mustafa Kamal can not affort to buy a new ticket, even if she was allowed to board the plane. Do you know if the parties involved would accept donations to allow for a new ticket to testify?

I would be very happy to donate.

Cheers,

Snafu

Pingback: Any Moment Now, Judge Alsup | Simple Justice

I think it is time for the United States to be abolished

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » “No-fly” trial: What happens now?

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » Judge orders more disclosure about what happened to daughter of plaintiff in “no-fly” trial

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » Defendants in “no-fly” case ignore judge’s deadline to make their arguments public

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » Government finally admits plaintiff was on the “no-fly” list

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » Does a US citizen need the government’s permission to return to the US?

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » More details of Judge Alsup’s decision in “no-fly” case

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » Lessons from the first “no-fly” trial

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » Blacklists and controls on the movement of goods and money

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » UN Human Rights Committee review of US implementation of the ICCPR: Day 1

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » Decision in first “no-fly” trial finally unsealed

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » FBI tells Dr. Ibrahim she’s not on the “no-fly” list

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » Feds change no-fly procedures to evade judicial review

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » Class action challenges Federal blacklists (“watchlists”)

Pingback: A 7-month-old baby on the no-fly list? Yup. But that's not the most absurd thing about it. | Bullet Metro

For as much of a claim that the DHS is to fight and secure the US from threats, based on this story I’m sure organizations such as ISIS may be jumping up for joy since these types of actions are the kind that helps persuade people into joining terror groups such as ISIS.

Pingback: A 7-month-old baby on the no-fly list? Yup. But that's not the most absurd thing about it. - virsl.com

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » Palantir, Peter Thiel, Big Data, and the DHS

Pingback: Kudos to Lufthansa. Coals to the DHS. | Papers, Please!

Pingback: New “National Vetting Center” will target travelers | Papers, Please!

Pingback: A broader legal challenge to Federal blacklists | Papers, Please!