Briefing completed following “no-fly” trial

Today the parties in Ibrahim v. DHS submitted what were scheduled to be their final written responses to questions from the judge following the first trial in any of the cases challenging U.S. government “no-fly” orders:

- Court’s Order re Clearance

- Plaintiff’s Response to the Court’s Order re Clearance

- Defendants’ Response to the Court’s Order Requesting Briefing on Access by Opposing Counsel to Classified Information

The plaintiff’s brief in particular is worth reading in its entirety.

The case is now in the hands of U.S. District Judge William Alsup, who could either issue some sort of ruling deciding some or all of the issues before him, or ask for yet more input from the parties.

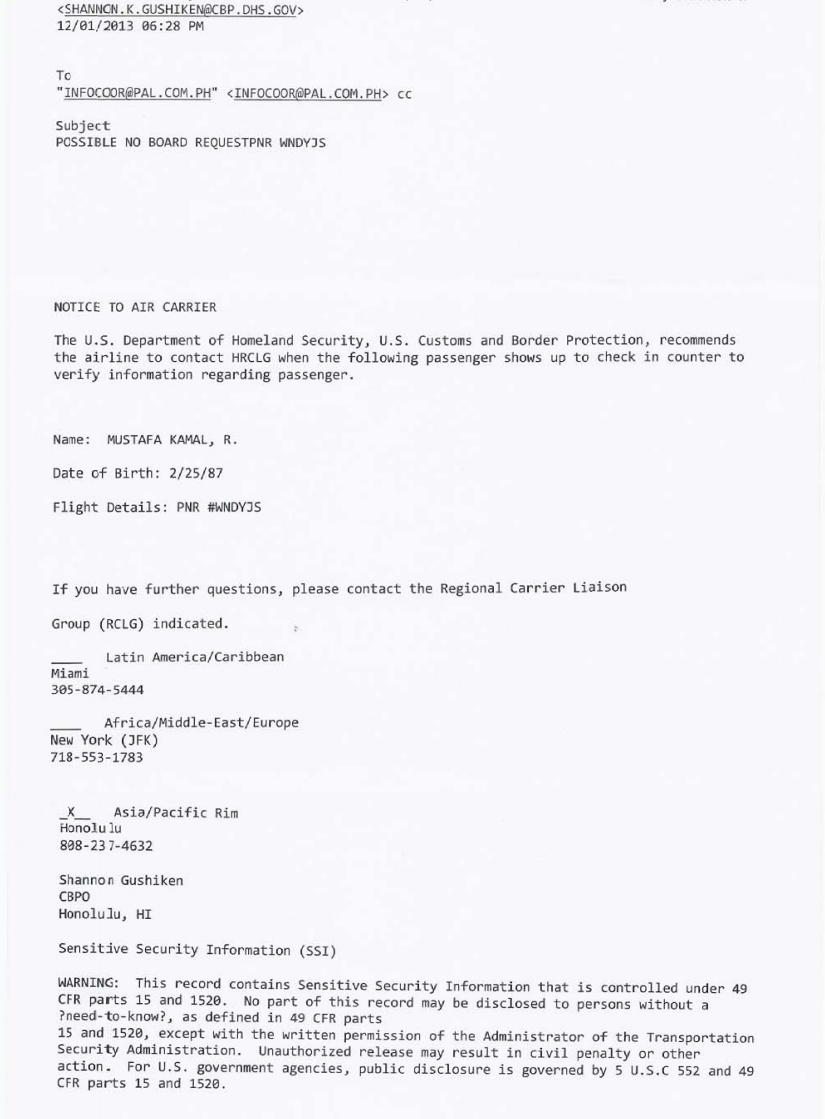

Today’s briefs from lawyers for the plaintiff (Dr. Rahinah Ibrahim) and the defendants (Federal agencies and officials responsible for interfering with her right to travel) address the specific questions about secrecy most recently posed by Judge Alsup: Whether the plaintiff’s lawyers could obtain clearances from the government to see the “secret” evidence most recently proffered by the government (1) (2) and if so, whether any of Dr. Ibrahim’s lawyers would be willing to submit to the clearance process and how long it would take.

Dr. Ibrahim’s lawyers point out that the defendants have already said that they “‘oppose any procedure that would provide classified information to Plaintiff’s counsel.’ Plaintiff’s counsel understand this to mean that the executive will not exercise its discretion in favor of granting a security clearance to plaintiff’s counsel.”

But even if the defendants are now willing to consider giving one or more of the opposing lawyers their “permission” to see the evidence they want the judge to rely on, “the government historically has contended that classified information can be withheld even from cleared counsel”:

Although at first blush it may seem like a feasible alternative to just get counsel “cleared,” in reality, any order to that effect will only provide defendants the ability (1) to arbitrarily deny plaintiff and her counsel access to classified information; (2) to conduct unfettered investigations into the personal lives of plaintiff’s counsel and their friends and family members; and (3) to hold up the case for months if not years while defendants conduct the investigation. It would cede authority over the progress in this case to an interested party, the defendants. The Executive already has enough of an advantage.

Despite all this, Dr. Ibrahim’s lawyers offer that one of more of them is willing to undergo the process of applying for a clearance to see the “secret” evidence the government wants to use against their client, provided that they are allowed “adequate access and opportunity to be heard regarding the information upon which defendants rely”, including to “discuss the information with their client so that she and they may rebut any allegations contained in the secret information.”

That’s sure to be a deal-breaker for the government defendants, who have been adamant that Dr. Ibrahim not be allowed ot know her status on any “watchlists” or the reasons for it. But this speaks directly to the concerns expressed by Judge Alsup during closing arguments in the trial regarding a person like Robert Oppenheimer who, without knowing the details of the allegations and evidence against him, wouldn’t know what exculpatory or rebuttal evidence to bring forward. It’s not enough for one of Dr. Ibrahim’s lawyers to learn the evidence against her client, if she can’t use that information to defend herself.

Dr. Ibrahim’s lawyers also argue that, regardless of the classification status of the “secret” evidence or the “clearance” status of any of the lawyers, Judge Alsup has the authority to decide the conditions under which the plaintiff and her lawyers can see the evidence:

Ibrahim has argued throughout this case that the supreme law of the land, the United States Constitution, and specifically the due process protection found in the Bill of Rights, requires that defendants provide adequate notice of the purported bases for their decision wrongfully to label her a terrorist and diminish her rights, including any classified information that is required to enable Ibrahim to respond to the accusations against her…. The Bill of Rights trumps defendants’ executive orders and evidentiary privileges…. The Court may overrule the state secrets privilege asserted by defendants and allow plaintiff and her counsel access to the information under appropriate protective orders.

The defendants don’t say whether they would “clear” any of Dr. Ibrahim’s lawyers to see the “secret evidence they want to show only to Judge Alsup (1) (2). But they argue that the decision on access to information they deem “secret” is solely up to the Executive, i.e. to themselves. That would leave it up to the defendants to decide which evidence the plaintiff or her lawyers could see, since all of the agencies and officials responsible for clearance and classification decisions are defendants in the case. The judge, they say, has no authority to second-guess or overturn their decisions. The defendants also indicate that they would immediately appeal any decision by Judge Alsup to allow any of Dr. Ibrahim’s lawyers or Dr. Ibrahim herself to see any of the “secret” evidence (1) (2) that they have submitted to the judge in camera and ex parte.

Judge Alsup asked for briefs on whether any of Dr. Ibrahim’s lawyers could or would obtain clearances to enable them to see the government’s latest “secret” (in camera and ex parte) submissions to the court. Most of today’s briefing, however, was devoted to the follow-up question Judge Alsup didn’t ask: What should the judge do if none of Dr. Ibrahim’s lawyers are able and/or willing to obtain such clearances and access to the “secret” evidence on terms acceptable to both sides in the case?

The defendants argue that they can’t “defend” themselves without using one or another sort of “secret” evidence. Since they say the evidence must be kept secret, and their decision on “secrecy” is not subject to review by the trial judge, the case against them must be dismissed. That seems to beg the question of why, if the case can be decided without the “secret” evidence, the defendants submitted it to the judge in the first place. (Or, more precisely, in the last place, since they waited to do so until after the trial, after trying to submit secret evidence and arguments earlier in the case but being told by Judge Alsup that he wouldn’t even look at it: “[T]he Court will ignore all of the redacted material … and will rule on the same paperwork made available to both sides.”) If the defendants have offered Judge Alsup an explanation of that, it’s in the secret briefs (1) (2) that accompanied the secret evidence.

Dr. Ibrahim’s lawyers argue that Judge Alsup can reach the opposite conclusion, and find that Dr. Ibrahim has been denied the due process to which she is entitled, without needing to consider the “secret” evidence proffered by the defendants (“The government’s attempts now to use secret evidence to deprive plaintiff of a remedy serve as further evidence they have deprived plaintiff of due process”), and (2) the “secret” evidence is, at this point, inadmissible, for numerous reasons:

- Secret evidence violates plaintiff’s Fifth Amendment right to due process, her right to a trial, and her right to confront her accuser.

- Just because something is classified does not make it true. Before the Iraq war in 2003, a number of classified reports said that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction. We all know how that turned out. See, e.g., http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2012/09/05/a_classified_CIA_mea_culpa_on_iraq%20#sthash.UyoTPxlR.dpbs.

- To the extent the government’s secret submissions rely on documents, reports, or declarations of witnesses to prove the truth of matters asserted, they are inadmissible hearsay.

- The government waived its right to use the secret evidence because it repeatedly represented to the Court that the effect of its privilege assertion was to “exclude the evidence from the case,” waiting until after trial to offer the alleged evidence that allegedly requires dismissal. For the same reason, the government is estopped from arguing for dismissal on these grounds.

- The secret evidence is also late because the government submitted it only after witnesses were excused and after the matter was submitted.

So far as we can tell, the case now stands submitted to Judge Alsup for his decision.