We endorsed neither Hillary Clinton, Donald Trump, nor any other candidate for elected office. So what does the presumptive election of Donald Trump as President of the U.S. — when the electors cast their ballots on December 19, 2016, and the votes are counted on January 6, 2017 — mean for the work of the Identity Project?

First and foremost, it means that our work, and the need for it, will continue — as it has under previous administrations, both Democratic and Republican.

Human and Constitutional rights are, by definition, no more dependent on the party affiliation of the President, if any, than on our own. Freedom is universal. Our defense of the right of the people to move freely in and out of the U.S. and within the country, and to go about our business, without having our movements tracked and our activities logged or having to show our papers or explain ourselves to government agents, has been and will remain entirely nonpartisan.

We will continue to criticize those who restrict our freedoms and infringe our rights, regardless of their party, just as we have criticized the actions of both the Obama and Bush administrations and of members of Congress and other officials of both parties, many of whom remain in power despite the changes at the top.

Attacks on our liberty have been, and remain, just as bipartisan as our resistance to them. This is especially true of the imperial power which the Presidency has been allowed to accrue, and which is exercised through Presidential proclamations, executive orders, and the secret law (or, to be more accurate, lawlessness) of Federal agency “discretion”. Those who acquiesced in the expansion of Presidential power and executive privilege because they thought that it would be used to their benefit by a President of their own party have only themselves to blame if that power is later used against them by a new President of a different party, or without allegiance to a traditional party hierarchy.

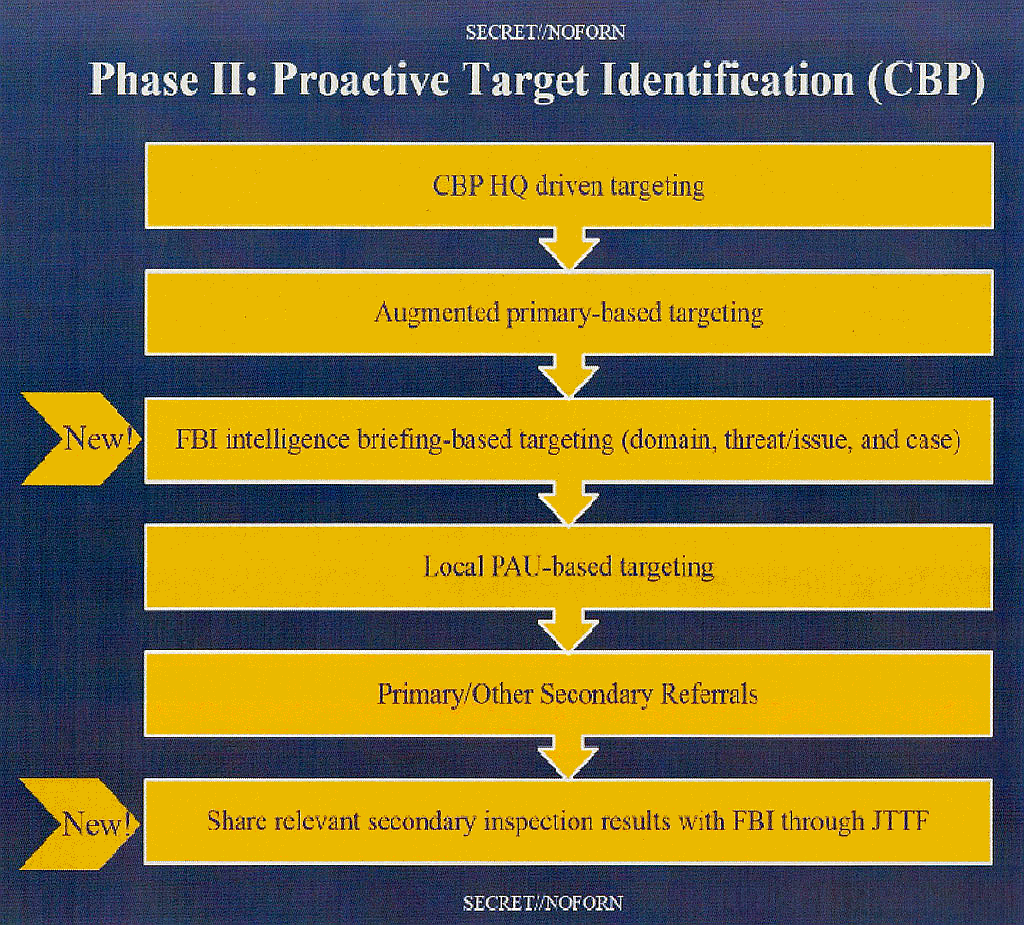

Many of the most imminent ID-related threats are those that arise from existing laws or extrajudicial administrative practices, the limits of which — in the absence of legislative or judicial oversight and checks and balances — are set solely by executive order. Where President Trump can make changes to ratchet up repression, to register and track both U.S. and foreign citizens, and to monitor and control our movements within the country and across borders, with the stroke of a pen, we don’t expect that he will hesitate to wield the power he has inherited to govern by issuing public decrees or by giving secret orders to his minions.

In some of these cases, Federal officials and the homeland-security industrial complex of contractors, confident that the incoming occupant of the White House will bless their efforts to anticipate has desires, may take action even before they are ordered to do so. This seems especially likely, in our area of concern, with respect to (1) the DHS implementation schedule and requirements for the REAL-ID Act, (2) the TSA’s longstanding desire to enforce and eliminate exceptions to a de facto ID requirement for air travel that lacks any basis in statute and contravenes the U.S. Constitution and international law, and (3) expanded use of ID and surveillance-based pre-crime profiling (President-to-be Trump calls it “extreme vetting”) as the basis for control of movement, especially across borders.

We will be watching closely and reporting on signs of activity on all these fronts, some of which are already visible.

Now more than ever, we need your support — not just helping us to defend your rights, but asserting your rights and taking direct action to defend them yourselves. “The limits of tyrants are prescribed by the endurance of those whom they oppress.”

We invite you to join us in our continued resistance to all lawless attacks from any and all sides on our Constitution, our freedom, and our human rights.