Our work is cited in an article today by Kaveh Waddell in The Atlantic, “How Long Can Border Agents Keep Your Email Password? Some data gathered from travelers going through customs can stay in a Homeland Security database for 75 years.”

The article in The Atlantic highlights several recent incidents in which international travelers have been asked or ordered to tell US Customs and Border Protection inspectors the passwords to their electronic devices and/or online accounts. As in many encounters with law enforcement officers or other government agents, the distinction between a request and a command at an airport or international border is often unclear.

In one of these incidents, a Canadian would-be visitor to the US provided CBP with the password to his phone, but balked at providing the password to his accounts with LGBT dating apps and websites. He forfeited his ticket, and left the US “preclearance” site at the airport in Vancouver without boarding his intended flight to the US. A month later, when he tried again to fly to the US, carrying the same phone with the password unchanged, he found that CBP had recorded his phone password in their permanent file about him in the CBP “TECS” lifetime international travel history database.

This sort of data collection and data retention is wrong, but it’s also routine and should be expected.

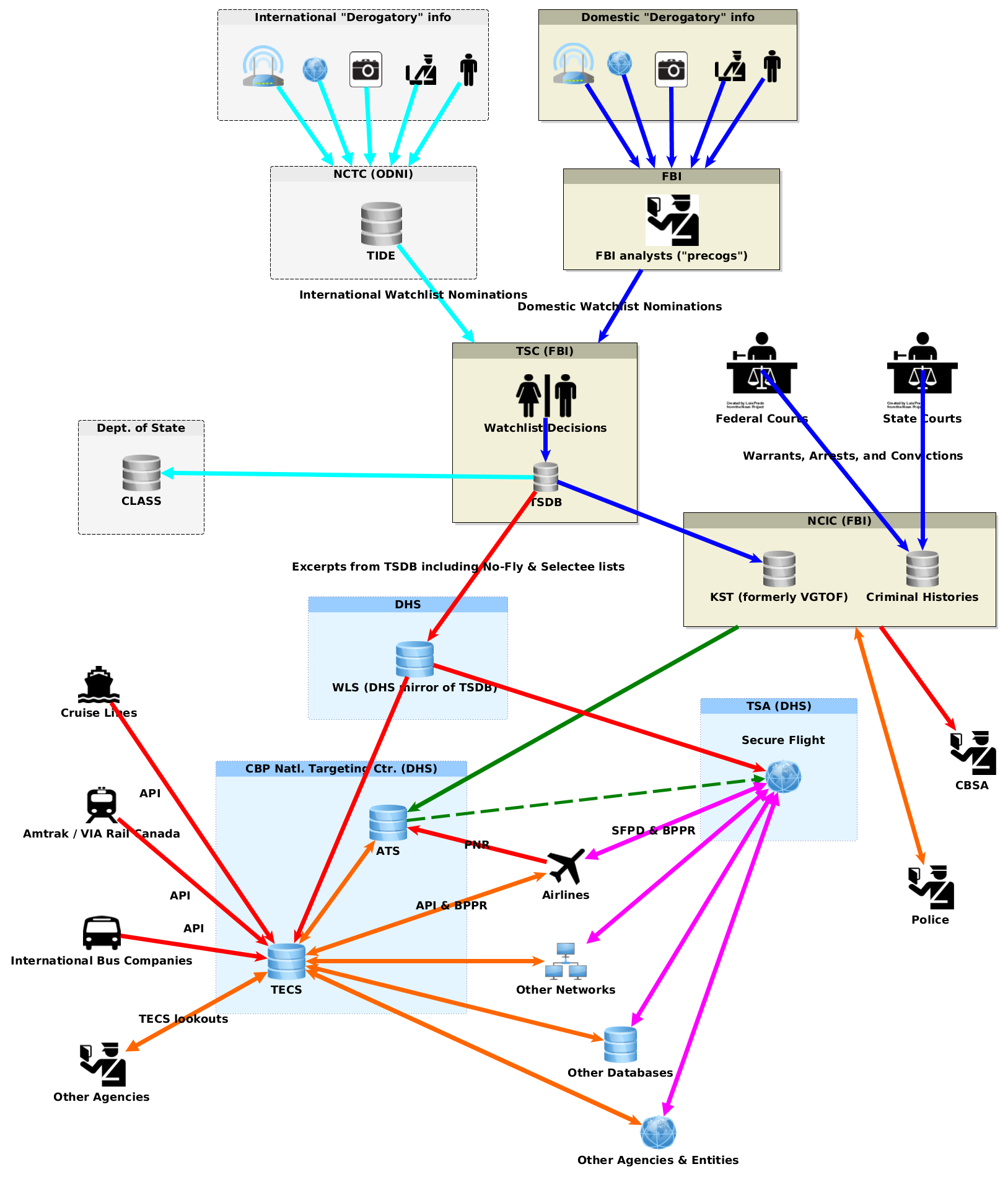

For more than a decade, since DHS first disclosed the existence of its “Automated Targeting System” database, we’ve been providing forms you can use to request the files about you from TECS and other government databases, helping travelers interpret the (redacted and incomplete) responses from CBP, and reporting on what we’ve seen in the responses and how these dossiers are used in pre-crime profiling and control of who is “allowed” to fly and how they treated when they fly.

We’ve sued to obtain our travel records from CBP and information about how these databases are mined and shared by CBP and other government agencies.

After ignoring our requests for three years, DHS exempted the system from most of the requirements of the Privacy Act, including limits on data retention, when the agency realized we were about to sue.

Any disclosure to us of the government’s permanent files about our travel is now a matter of “discretion”, not a right, if we are US citizens, and expressly forbidden by an Executive Order of President Trump for anyone other than US persons. As we told The Atlantic:

“Any limits would have to be derived directly from the Constitution or international treaties, not from statutes or regulations,” said Edward Hasbrouck, a travel expert and consultant to The Identity Project. “I am not aware of any case law limiting retention of this sort of data.”

Here’s what our experience and our research confirms: CBP officers are not your friends, and their job is not to help you. They are law enforcement officers. Their job is to find evidence of violations of the law, and/or reasons to deny you entry to the US. Anything you say to them can be retained and used against you at any time in the future, just like anything you say to any other law enforcement officers. You should expect that anything you have with you, anything you say, and anything you do at an international border, airport, or CBP checkpoint can and will be recorded. That information can and will be retained by DHS for the rest of your life. You could be questioned about it in any future encounter with CBP or other law enforcement or government agents, even many years later, and have it used against you or anyone else in court at any time, perhaps in ways you could never anticipate.

We’ve seen all sorts of information — irrelevant, inappropriate, and potentially subject to derogatory interpretations or giving rise to guilt by association — in CBP travel dossiers. We’ve been questioned at a US border crossing, years later, about completely inconsequential and legal events at another airport years earlier, because those were being recorded in the TECS database even during primary screening on a routine entry to the US by a US citizen.

What can you do, and what should you do, if you are asked to tell CBP agents any of your passwords?

We agree with all the lawyers consulted by The Atlantic: US citizens should not voluntarily provide passwords to US border guards or inspectors at airports.

Read More →