Information about what happened in Ibrahim v. DHS – the first “no-fly” case to make it to trial — has trickled out gradually, making it hard to get a clear picture of what has happened.

The court was cleared at least ten times during the week-long trial for testimony, introduction of evidence, and legal arguments that the government claimed had to be kept secret. Many of the documents, exhibits, declarations, legal briefs, and even the judge’s opinion remain sealed, in whole or in part. Key information has to be pieced together by reading between the redactions, or from passing mentions in open court, the meaning of which only becomes clear in light of other fragmentary revelations.

Most mainstream media didn’t cover the trial, covered it only from the written record, or attended only small portions of the proceedings. We attended and reported on as much of the trial as was open to the public, but at times, we were the only reporter or member of the public in the courtroom.

The government still has until March 14th to decide whether to appeal, and the remaining sealed portions of the judge’s opinion aren’t scheduled to be released until April 15th. Key portions of Judge Alsup’s findings including what happened to Dr. Ibrahim’s US-citizen daughter are still secret. But in the meantime, what are our key takeaways from this trial?

(1) Congress needs to close the loopholes in the Privacy Act, which was enacted in 1974 to prevent exactly this sort of injustice, and would have done so but for its exemptions, exceptions, and lack of enforcement.

The purpose of the Privacy Act was to prohibit the government from using secret files as the basis for decisions about individuals, without allowing the subjects of those files to inspect and correct them. But agencies are allowed to exempt entire systems of records from these requirements. The DHS and the FBI (keeper of the Terrorist Screening Database which includes the “no-fly” list) have exempted their watchlists and blacklists and the allegedly derogatory information on which watchlisting and blacklisting decisions are based. In addition, although privacy is a human right protected by international treaty, the Privacy Act only protects U.S. citizens and residents. Other foreigners have no rights under this law, even when the U.S. government is using secret files to make decisions about their exercise of their rights.

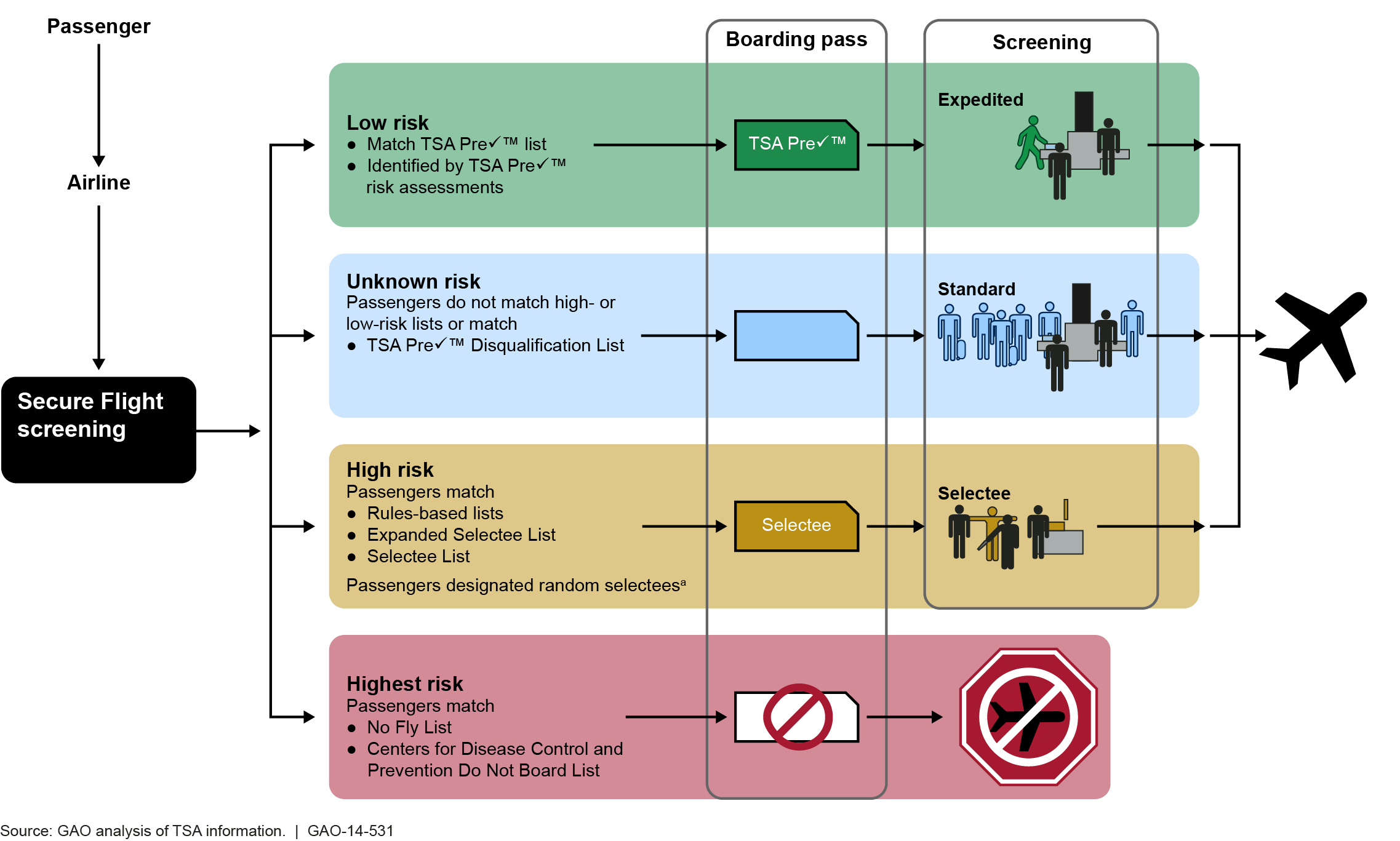

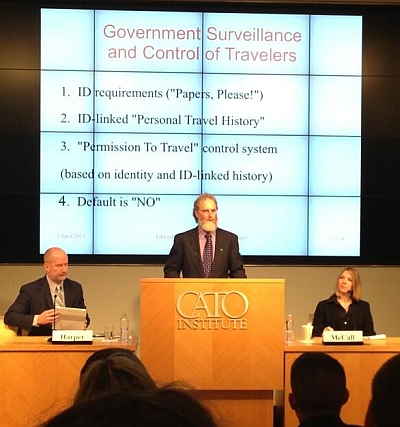

(2) The watchlisting form and process incorporates presumptions in favor of surveillance and restrictions on travel, rather than presumptions of innocence and of travel as a right.

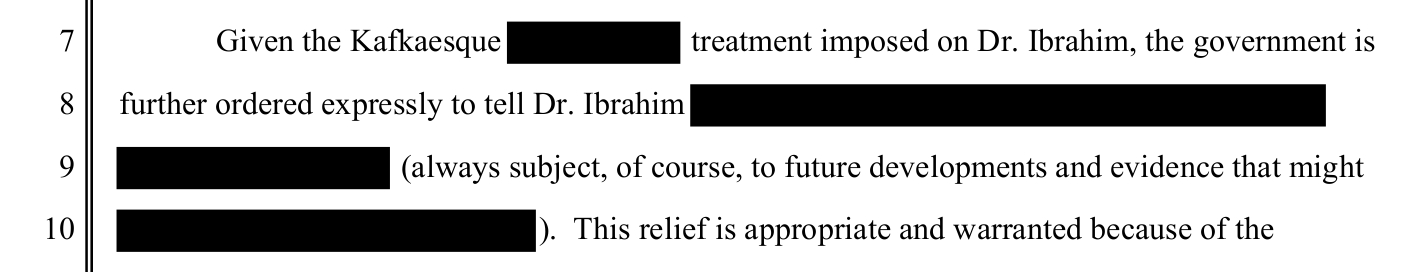

As was made clear in the latest redacted version of Judge Alsup’s findings, Dr. Ibrahim was placed on the “no-fly” list because FBI Agent Kelley left the box on the “nomination” form for “no-fly list ” blank:

This negative check-off form might look like poor user-interface design, but it actually exposes the real mindset of those who believe that travel is a privilege for which the traveler bears the burden of justification: “Better to restrict the rights of innocent people than to leave anyone off the watchlist.” Once the threshhold decision to place a name on a “watchlist” is made, the default is a categorical ban on all air travel and the widest possible dissemination of the blacklist information to other agencies and other countries’ governments (TUSCAN to Canada and TACTICS to Australia).

(3) There are no meaningful internal or administrative safeguards on no-fly and watchlist decisions. Administrative agencies cannot police their own secret internal actions. Transparency and independent judicial review are the only way to safeguard rights.

The DHS and FBI have claimed that internal administrative reviews of watchlist “nominations” are adequate safeguards against wrongful agency actions, and make judicial review unnecessary. In this case, Agent Kelley’s mistake was obvious on inspection, and would have been detected as soon as anyone checked whether the action ordered by the form was supported by the rest of the file. Nobody did so until after Dr. Ibrahim had been arrested and further mistreated when she tried to check in for her flight. If anyone “reviewed” or approved Agent Kelley’s nomination of Dr. Ibrahim to the no-fly list, they rubber-stamped the form without ever looking at the rest of the file, much less making an independent assessment of the factual basis for the decisions. This was the essence of Judge Alsup’s due process findings.

(4) The problem is not limited to the “no-fly list”, and there is no clear line between a “watchlist” and a blacklist. You can’t build a system of surveillance and individualized dossiers without it inevitably having consequences for people’s lives. The travel dataveillance system needs to be dismantled, and the whole database needs to be purged.

In the portion of her closing arguments conducted in open court, Dr. Ibrahim’s attorney, Ms. Elizabeth Pipkin, stated that Dr. Ibrahim and her daughter, Ms. Raihan Mustafa Kamal, had “the same status on the no-fly list”.

Presumably that common status was that neither woman was on the no-fly list. The government claimed that its “mistake” (in placing Dr. Ibrahim on the no-fly list) was corrected the same day as her arrest in 2005, and that it had not prevented Ms. Mustafa Kamal from flying to San Francisco to attend and testify at her mother’s trial.

Neither Dr. Ibrahim nor Ms. Mustafa Kamal are on the “no-fly” list. But when FBI Agent Kelley’s mistake in putting Dr. Ibrahim on the no-fly list was corrected, she was moved to, or left on, one or more watchlists — as Agent Kelley had intended. At some point Ms. Mustafa Kamal was also placed on one or more watchlists. Agent Kelly’s reasons for his intended decision to place Dr. Ibrahim (and perhaps Ms. Mustafa Kamal — we don’t know if she was watchlisted at the same time or separately, by whom, or why) on one or more watchlists remain secret, and were never disclosed to Dr. Ibrahim or her attorneys or reviewed by the judge. Because the government admitted that the no-fly listing was unwarranted and a mistake, the court never reached the question of what to do if the government claims that a listing was justified.

The “no-fly” list and the government’s other “watchlists” aren’t actually separate lists. Both are contained in the consolidated Terrorist Screening Database (TSDB). The only difference between a “watchlist” entry and “no-fly” entry is a flag associated with an entry on the consolidated list.

According to a post-trial government filing, “Kelley designated Dr. Ibrahim as ‘handling code 3.’… The majority of individuals in the TSDB are assigned the lowest handling codes – codes 3 and 4.” That same “status” — not flagged as a “no-fly” listing, and with one of the lowest “handling codes” — was sufficient to cause the DHS to send a message to the airline on which Ms. Mustafa Kamal had reservations. That message induced the airline (as it was intended to do) to refuse to fulfill its duty as a common carrier or allow Ms. Mustafa Kamal to exercise her right, as a U.S. citizen, to travel to the US.

A watchlist sounds like a list of people who are subject to passive monitoring. In practice, “watching” or surveillance isn’t aimless. It’s for the purpose of making decisions affecting individuals. In the case of Ms. Mustafa Kamal, some other “watchlist” status had the same negative consequence, denial of boarding by an airline, as “no-fly” status. Dr. Ibrahim’s watchlist status (and perhaps the fact that she had once been on the no-fly list) led to her being unable to obtain a US visa, even lafter she was removed from the no-fly list.

In the future, “watchlist” needs to be understood as a euphemism for a de facto blacklisto that allows a level of deniability: “You’re not on the no-fly list. We just advised the airline not to let you fly.”

There’s no hard line between passive surveillance and active interference with individual’s activities. This lesson is well known to the FBI: Sending the FBI to question your employer can get you fired, even if the FBI is in theory merely collecting information and doesn’t order or explicitly recommend that you be fired.

Surveillance is itself stigmatizing, and stigma has consequences. During the Ibrahim trial, the government argued, verbally and in written pleadings, that it had not stigmatized Dr. Ibrahim because it “never” disclosed Dr. Ibrahim’s status on its lists to “anyone”. But in fact, the government disclosed Dr. Ibrahim’s status on the list, and later that of her daughter, to the airlines. These are precisely the entities to which it would be most damaging to have this stigma (suspicion of posing a threat to aviation) disclosed.

(5) The US government is willing to lie to the courts to try to hide its mistakes and misconduct.

Before, during, and after the trial, officials including Attorney General Eric Holder and Director of National Intelligence James Clapper and lawyers for the government defendants claimed that to disclose anyone’s status on any watchlist, or the basis (if any) for assigning that status, would “cause significant harm to national security.”

This continued even after Judge Alsup and Dr. Ibrahim’s attorneys knew how Dr. Ibrahim had been placed on the no-fly list and that the government did not consider her to pose any threat to aviation.

Dr. Ibrahim’s lawyers sought to depose Attorney General Holder and DNI Clapper regarding their sworn declarations supporting the assertion of “state secrets” privilege by Holder and the other defendants. On motion of Holder and the defendants, Judge Alsup quashed the subpoenas for those depositions.

On its face, the government’s assertion amounts to a claim that to disclose to the public that Dr. Ibrahim was put on the no-fly list because an FBI agent failed to check a box on a form would harm national security.

Does the government really expect us to believe that would-be terrorists are deterred by their belief that the FBI is infallible, so that disclosing that the FBI once made a mistake would unleash the forces of terror?

We don’t think so. The government lied to cover up its mistakes and to protect itself against deserved criticism, not to protect national security.

Remember that the next time the government claims that something must be kept secret “because terrorism”.