Another “deadline” for enforcement of the REAL-ID Act of 2005 passed uneventfully today.

The US Department of Homeland Security had advertised that DHS extensions of time for voluntary compliance with the REAL-ID Act by many states would expire today.

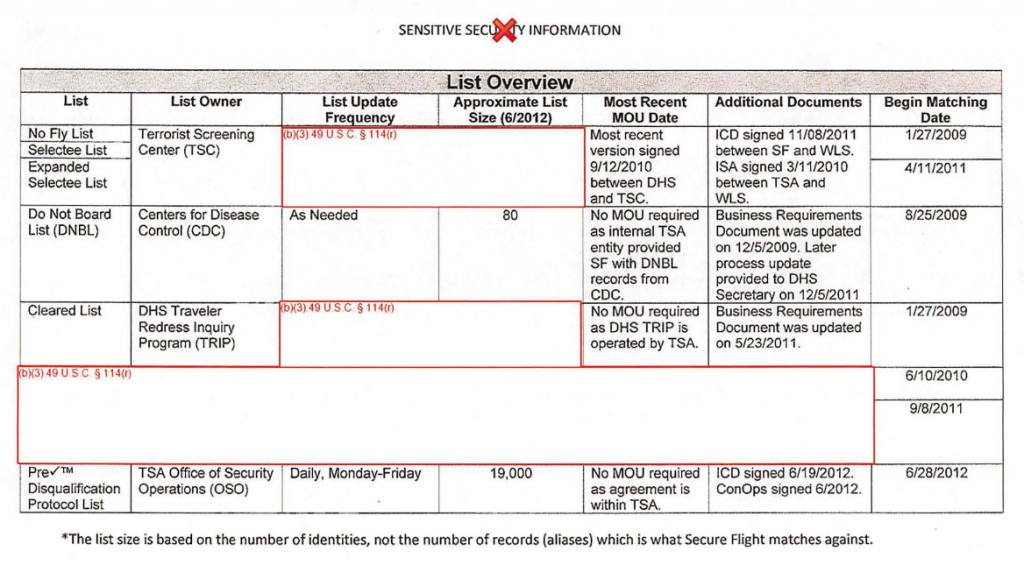

The DHS threatened that starting today it would “enforce” the REAL-ID Act through harassment or denial of the right to travel of airline passengers without ID or with ID issued by states or territories that the DHS, in its standardless administrative discretion, deemed insufficiently compliant with Federal wishes.

Today’s supposed “deadline” was fixed neither by law nor by regulation. Not surprisingly, the DHS blinked in the final days before its self-imposed ultimatum, as it has done again and again.

Every US state and territory subject to the REAL-ID Act was either certified by the DHS as sufficiently compliant to satisfy the DHS (at least for now), or was given a further extension of time to comply without penalty until at least January 10, 2019.

Yesterday, the day before the “deadline”, the DHS quietly posted notices on its website that it had granted further extensions until January 2019 to the last two states, California and New Jersey.

Perhaps the DHS is still unwilling to provoke riots at airports by stopping people without ID, or with ID from disfavored states and territories, from flying. Perhaps it isn’t yet prepared to face, and likely lose, the inevitable lawsuits from would-be flyers.

Even American Samoa, which — because the second-class status of American Samoans as US subjects but not US citizens would make it harder for them to challenge DHS restrictions of their rights — had been the first trial by the DHS of enforcement of the REAL-ID Act, was given an extension until October 10, 2019.

So far as we can tell, REAL-ID Act “enforcement” meant only modestly enhanced harassment of American Samoans at airports. Our FOIA request for records of how many people tried to fly with American Samoa IDs, and what happened to them, remains pending with no response after more than five months.

American Samao isn’t the limit of REAL-ID Act expansion beyond US borders and overseas. H.R. 3398, a bill to extend eligibility for REAL-ID Act compliant drivers licenses and IDs to citizens of several nominally independent de facto US dependencies, has passed the House and is pending in the Senate.

Meanwhile, the real movement toward state compliance with the REAL-ID Act is behind the scenes — as the DHS, its collaborators among state driver licensing agencies, and AAMVA, the operator of the outsourced and pseudo-privatized national ID database, want it to be.

Since we last reported on the status of REAL-ID Act compliance six months ago, agencies in three more states — Pennsylvania, New Mexico, and most recently Washington in September 2018 — have uploaded information about all licensed drivers and holders of state-issued IDs to the SPEXS national database. That brings to 19 the number of states whose residents’ personal information is included in the aggregated database.

But even as the database grows to include information about more and more US residents, the DHS persists in denying its existence. According to the DHS public FAQ about the REAL-ID Act:

A: Is DHS trying to build a national database with all of our information?

No…. REAL ID does not create a federal database of driver license information.

To the extent that there is any truth at all in this statement, it’s that the SPEXS national database isn’t under direct Federal or state control, but has been handed over to AAMVA and AAMVA’s contractors. (The database is apparently actually hosted by Microsoft.)

For obvious reasons, nobody is more eager than AAMVA to have you pay no attention to the national ID database behind the REAL-ID Act curtain.

In June 2018, we were honored to receive an urgent letter by Fedex from the President & CEO of AAMVA, demanding that we immediately remove from our website the specifications for the SPEXS database, which we had obtained in 2016 from AAMVA’s own public website. After AAMVA made that whole section of its site “members-only”, we posted a copy of the SPEXS specification to help readers understand the details of the system, and as one of the key sources for our analysis of SPEXS.

SPEXS already includes personal information obtained from government records of drivers licenses and state IDs, including dates of birth and the last five digits of Social Security Numbers, for more than 50 million US residents. We think the people whose data is included in this system are entitled to know what information is being kept about them, who has access to it, and how it is used.

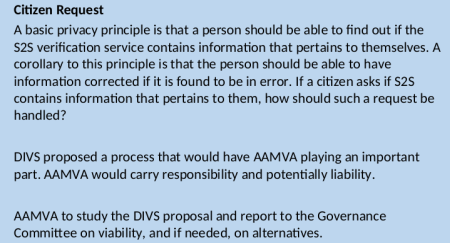

According to the SPEXS specifications, development of SPEXS was funded by grants from components of the DHS and the Department of Transportation. (We’re waiting for responses to our FOIA requests for those agencies’ records about SPEXS.) If SPEXS were being operated directly by a Federal agency, the Privacy Act would require it to provide notice of the types of records in the system, how they are used, and with whom they are shared, as well as procedures for individuals to see the records about themselves and to obtain an “accounting of disclosures” to third parties of information about themselves.

But because the SPEXS database has been outsourced to a nominally private contractor, AAMVA, both Federal and state agencies can disclaim any responsibility for it. That leaves the SPEXS specifications as the best available evidence of what the system is and does.

In a later message to our Web hosting provider, a lawyer for AAMVA claimed that, “The information contained in this work is sensitive and its unauthorized publication could jeopardize the security of the governmental program to which this document relates.” This is nonsense. AAMVA waived any claim of sensitivity by making the specifications public.

When it was still struggling to sell the first states on buying into SPEXS, AAMVA posted the SPEXS specification on its website for anyone to download. More than two years after we called attention to what this document reveals, AAMVA is trying to suppress it. Not because it contains any secrets — it’s been publicly available for years — but because it conclusively disproves the DHS big lie that there is no national REAL-ID database, and shows the essential role that AAMVA itself is playing in this surveillance system.

We encourage you to pay close attention to the AAMVA man behind the REAL-ID Act curtain. And if you have questions about SPEXS or the SPEXS specifications, feel free to contact us.