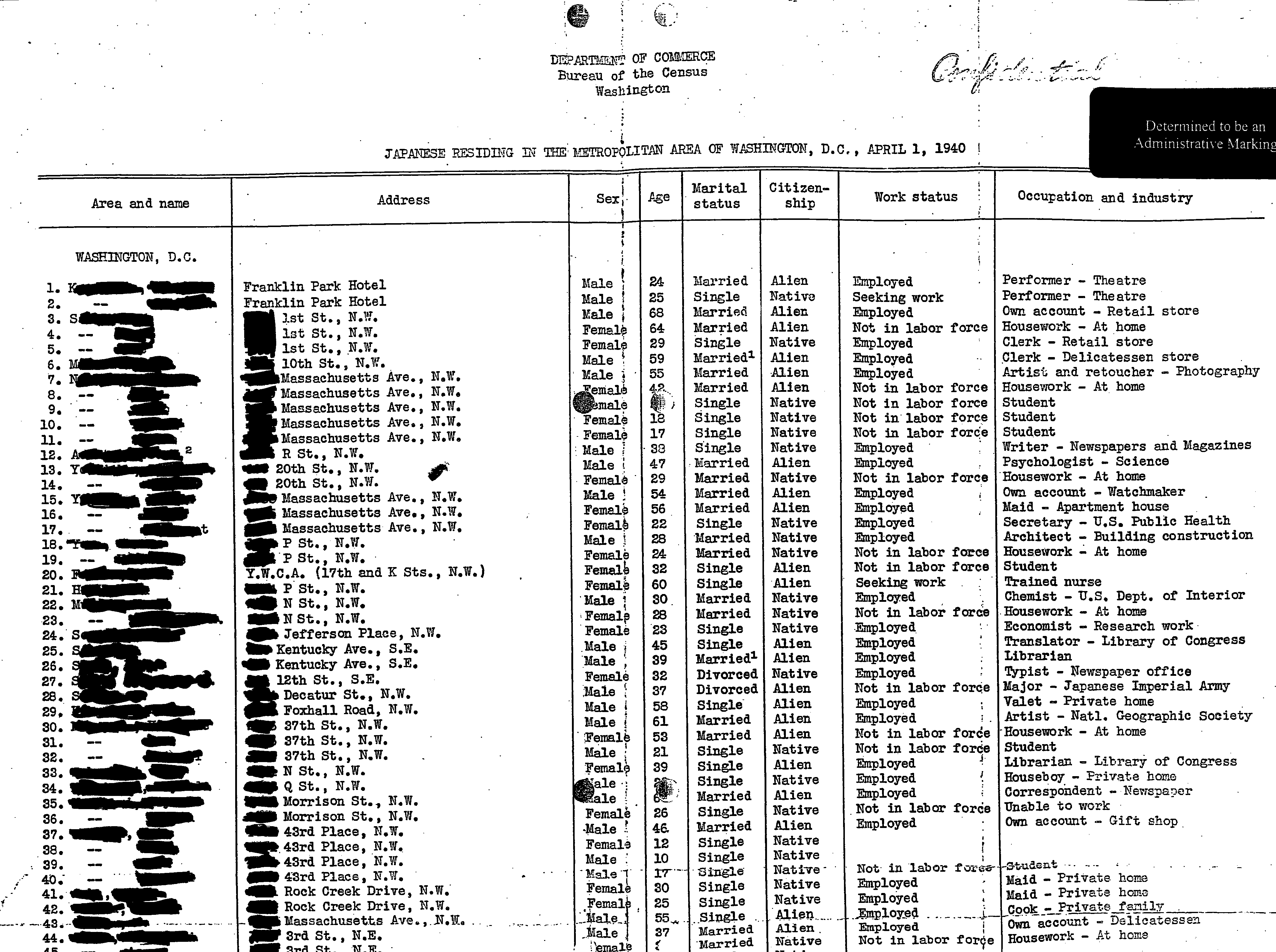

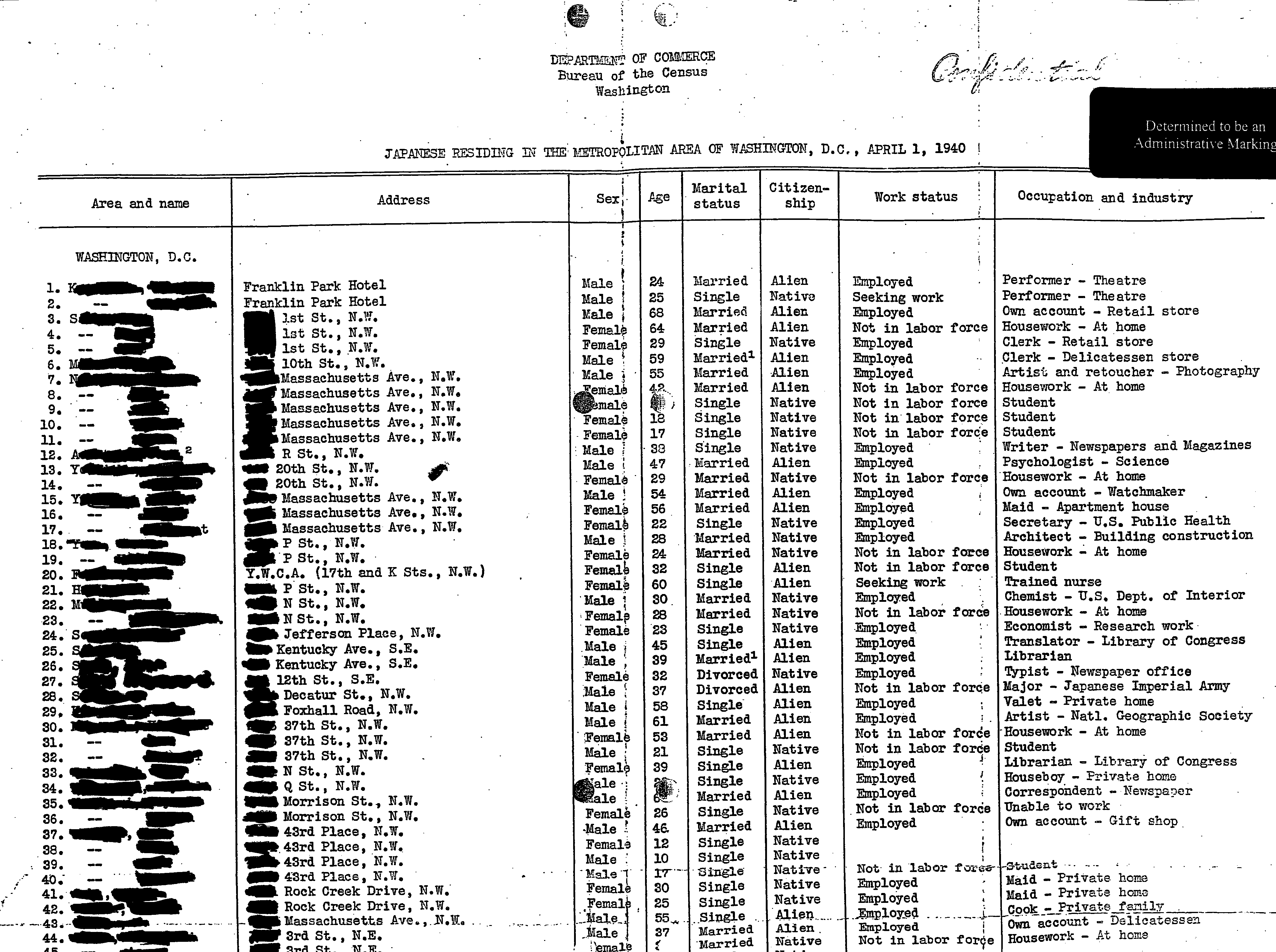

[Excerpt from census report used for internment of Japanese-Americans. Names and street numbers were redacted by the academic researchers who published this, but were included in the original report provided to internment authorities and later found in government archives.]

[Excerpt from census report used for internment of Japanese-Americans. Names and street numbers were redacted by the academic researchers who published this, but were included in the original report provided to internment authorities and later found in government archives.]

Yesterday 17 more states, the District of Columbia, and six cities joined the state of California in court challenges to plans for the 2020 Census to include a question about the citizenship of each person found to be present in the US on census day.

Like police, census takers can ask any questions they like. But if they ask questions such as, “Are you a US citizen?”, you can, and you should, exercise your right to remain silent.

The US Constitution requires to Federal government to conduct a census — a count — every ten years. But you don’t have to say anything for the government to count you.

Anything you say to the US Census can and will be used against you.

How do we know this? We know it could happen again, because it has happened before.

In 1943, the Bureau of the Census prepared block-by-block reports based on responses to the 1940 census listing the name, street address, age, occupation and employer, and citizenship of each Japanese or Japanese-American person. A sample of one of these reports is reproduced at the top of this article.

These census reports were turned over to the military authorities administering the round-up and “internment” (a euphemism) of Japanese and Japanese-American people. Archived copies of these reports were found in the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and published by academic researchers in 2007.

Responses to census questions were thus used against (Japanese-American) US citizens as well as against (Japanese) foreign citizens who resided in the US.

This documented history teaches that it’s not just immigrants and foreigners who should decline to answer census questions. US citizens have a well-founded fear that answers to census questions about lawful status — there was nothing illegal or sanctionable, at the time of the 1940 census, about being of Japanese ancestry — can be and have been used against them.

Today, the Bureau of the Census claims that “We promise that we will use the information only to produce timely, relevant statistics about the population and the economy of the United States.” According to the Census Bureau FAQ on “Why We Ask Questions About… Citizenship“:

We use your confidential survey answers to create statistics…. no one is able to figure out your survey answers from the statistics we produce. The Census Bureau is legally bound to strict confidentiality requirements. Individual records are not shared with anyone, including federal agencies and law enforcement entities. By law, the Census Bureau cannot share respondents’ answers with anyone — not the IRS, not the FBI, not the CIA, and not with any other government agency.

History shows, however, that it times of war, panic trumps previously declared policy. The “War on Terror” is no exception.

The only way to prevent the misuse of information is not to collect it. Unless the current lawsuits are successful, the only way to prevent the census from collecting this information will be for people questioned by census takers to exercise their right to remain silent. If you want to be counted, you can show yourself at a window. You don’t need to say anything for the census taker to count you.

If someone claiming to be a census taker knocks on your door, don’t open the door. Claiming to be a census taker is a great pretext for identity theft, burglary, or home invasion. Ask them if they have a warrant or court order signed by a judge. If they don’t, tell them to them to go away. If they persist, say the same things you would say to police: “Go away. I do not consent to any search. I want to talk to a lawyer. I’m going to remain silent.”