CBP facial recognition is a service for the airline industry

After five years of foot-dragging in responding to our Freedom Of Information Act (FOIA) request, US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has finally released the pitch it made to the Future Travel Experience airline industry conference in 2019 on why airlines and airport operators should “partner” with CBP on automated facial recognition of airline passengers.

CBP claims in its presentation that “THIS IS *NOT* A SURVEILLANCE PROGRAM”. Its vision, however, is for CBP’s Traveler Verification Service (TVS) facial recognition system to provide automated identification of travelers at every stage of their journeys.

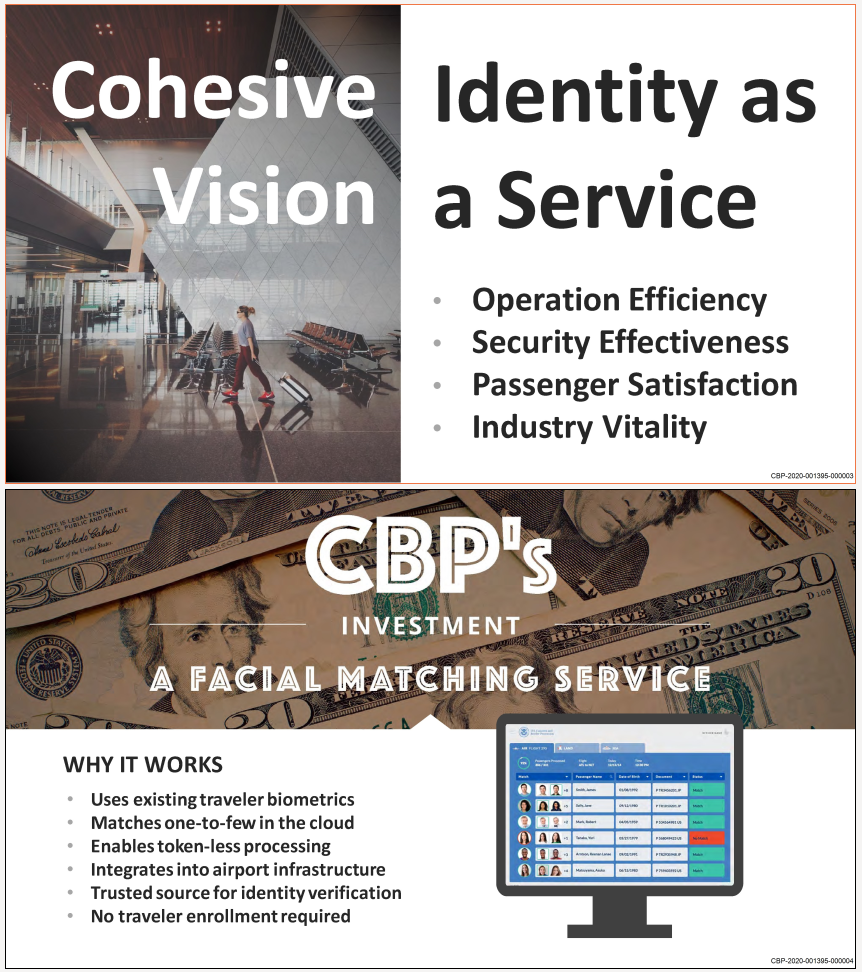

Airlines and airport operators won’t need to operate their own facial recognition software or databases. CBP will do that for them, allowing them to use TVS (which “integrates into airport infrastructure”, CBP boasts) for any of their business process automation, traveler profiling, personalized pricing, etc. purposes. Airlines and airport operators won’t need to store mug shots, since CBP will re-identify travelers for them as often as they want.

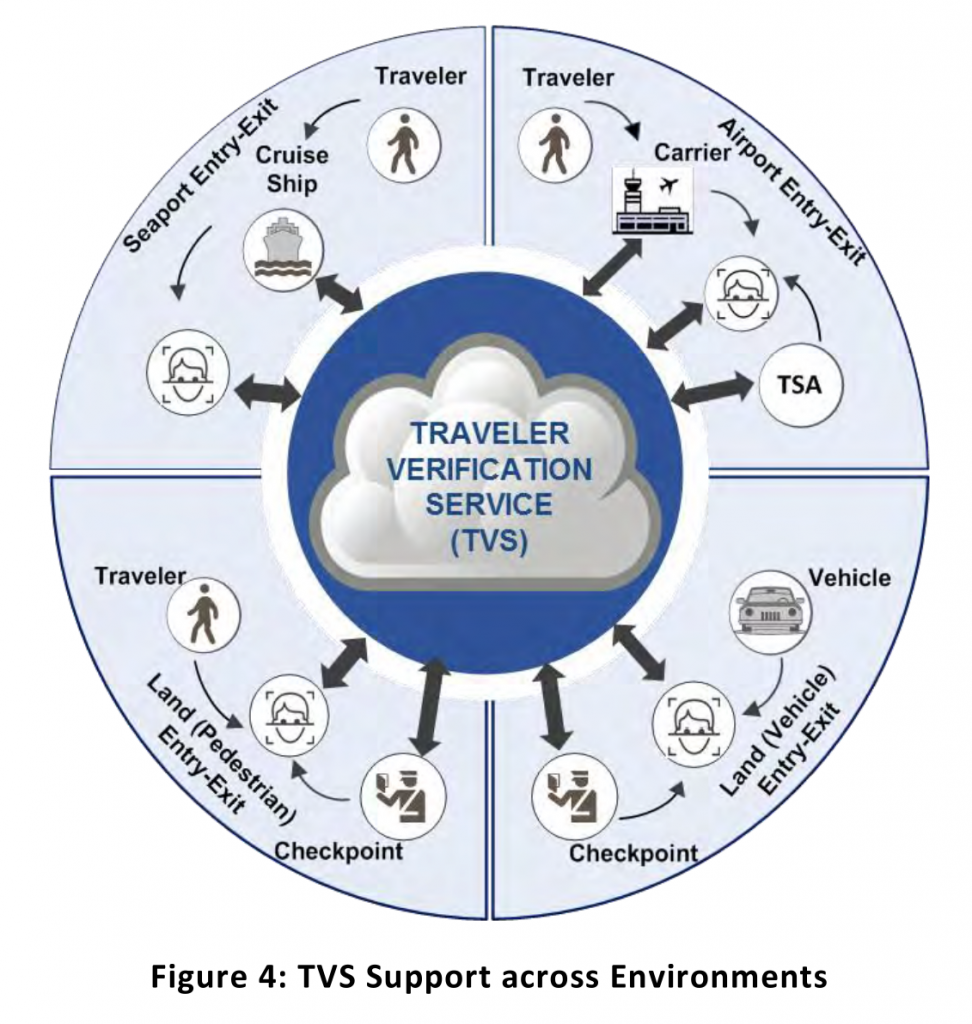

And that’s not all. The TVS facial recognition service will also be made available to cruise lines, bus companies, etc., to automatically identify travelers using all modes of transportation:

CBP will use a traveler’s face as the primary way of identifying the traveler…. This will create the opportunity for CBP to transform air travel by enabling all parties in the travel system to match travelers to their data via biometrics, thus unlocking benefits that… enhances the entire traveler experience.

The CBP “Biometric Pathway” will utilize biometrics to streamline passenger processes throughout the air travel continuum, and will provide airport and airline entities with the opportunity to validate identities against DHS information systems using the data available. CBP will partner with airlines, airports, and TSA to build a device independent, vendor neutral backend system called the Traveler Verification Service (TVS) that allows for private sector investment in front end infrastructure, such as selfservice baggage drop off kiosks, facial recognition selfboarding gates, and other equipment; this service will ultimately enable a biometric based entry/exit system to provide significant benefits to air travel partners…. The TVS will also be able to support future biometric deployments in the land and sea environments and throughout the traveler continuum. Figure 4 shows the different environments and touchpoints that will interact with the TVS.

Let’s make a deal”, CBP says to airlines and airport operators. “You provide the camera infrastructure embedded in passenger terminals at airports, and we’ll provide the facial recognition service.” It’s a Faustian bargain in which travelers are the losers, but already by 2019 many airlines and airports had taken CBP up on its offer. In the five years since, many more airlines and airports have joined CBP as collaborators in traveler identification, surveillance, and tracking.