First court ruling on a COVID-19 travel ban

Judge William Bertelsman of the U.S District Court for the Eastern District of Kentucky at Covington has issued a preliminary injunction prohibiting Kentucky state authorities from enforcing a “Travel Ban” order issued by Gov. Andy Beshear that prohibited most travel into or out of Kentucky, and required anyone crossing the state line to self-quarantine for fourteen days thereafter.

In so doing, and in concluding that “the Travel Ban does not pass constitutional muster,” Judge Bertelsman has become, so far as we know, the first Federal judge to opine on the Constitutionality of any of the hodgepodge of restrictions on interstate travel that have been imposed across the country in the name of control of the spread of COVID-19.

We are pleased that Judge Bertelsman correctly recognized that the Kentucky travel ban based its restriction on criteria (state lines and residency status that are meaningless to the novel coronavirus) that are unrelated to the protection of public health.

Covington, KY, is located directly across the Ohio River river from the larger city of Cincinnati, OH, with which it forms a single cross-border interstate metropolis. Judge Bertelsman sits in Covington, KY, but was born in Cincinnati, OH. The main airport for Cincinnati is located in Kentucky, not in Ohio, and uses the airport code “CVG” for Covington. In normal, non-pandemic times, more than 200,000 vehicles cross the bridges between Covington and Cincinnati every day, with no more thought than they would give to crossing a bridge within either state.

The ruling this week on the Kentucky ban on interstate travel came in a lawsuit, Roberts v. Neace, filed as a class action on April 14, 2020. The complaint raised objections both to the ban on interstate travel and to other provisions of Gov. Beshear’s executive orders restricting mass gatherings — including, but not limited to, gatherings for religious purposes — within the state of Kentucky.

Most of the argument on both sides, intervention by friends of the court, and news reporting about the case focused on the dispute over intrastate religion gatherings. Judge Bertelsman denied the plaintiff’s motion for a preliminary injunction on that claim, however, on the basis that it treated religious gatherings the same as all others, and was not specifically religious (or anti-religious) in intention or effect.

The claim that was upheld was against the interstate travel ban, on the following grounds which we hope that other courts considering similar cases will find persuasive:

The “‘constitutional right to travel from one State to another’ is firmly embedded in our jurisprudence.” Saenz v. Rose, 526 U.S. 489, 498 (1999) (quoting United States v. Guest, 383 U.S. 745, 757 (1966)). Indeed, the right is “virtually unconditional.” Id. (quoting Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618, 643 (1969)). See also United States v. Guest, 383 U.S. 745, 757 (1966) (“The constitutional right to travel from one State to another … occupies a position fundamental to the concept of our Federal Union. It is a right that has been firmly established and repeatedly recognized.”).

To be valid, such orders must meet basic Constitutional requirements. As the Supreme Court has stated: “(E)ven though the governmental purpose be legitimate and substantial, that purpose cannot be pursued by means that broadly stifle fundamental personal liberties when the end can be more narrowly achieved. The breadth of legislative abridgment must be viewed in the light of less drastic means for achieving the same basic purpose.” Aptheker v. Sec. of State, 378 U.S. 500, 508 (1964) (quoting NAACP v. Alabama, 377 U.S. 288, 307-08 (1964)).

The travel restrictions now before the Court violate these principles.

They have the following effects, among others:

- A person who lives or works in Covington would violate the order by taking a walk on the Suspension Bridge to the Ohio side and turning around and walking back, since the state border is several yards from the Ohio riverbank.

- A person who lives in Covington could visit a friend in Florence, Kentucky (roughly eight miles away) without violating the executive orders. But if she visited another friend in Milford, Ohio, about the same distance from Covington, she would violate the Executive Orders and have to be quarantined on return to Kentucky. Both these trips could be on an expressway and would involve the same negligible risk of contracting the virus.

- Family members, some of whom live in Northern Kentucky and some in Cincinnati less than a mile away, would be prohibited from visiting each other, even if social distancing and other regulations were observed.

- Check points would have to be set up at the entrances to the many bridges connecting Kentucky to other states. The I-75 bridge connecting Kentucky to Ohio is one of the busiest bridges in the nation. Massive traffic jams would result. Quarantine facilities would have to be set up by the State to accommodate the hundreds, if not thousands, of people who would have to be quarantined.

- People from states north of Kentucky would have to be quarantined if they stopped when passing through Kentucky on the way to Florida or other southern destinations.

- Who is going to provide the facilities to do all the quarantining?

The Court questioned counsel for defendants Beshear and Friedlander during oral argument about some of these potential applications of the Travel Ban, and counsel indeed confirmed that the Court’s interpretations were correct. (Doc. 38 at 9-13).

The Court is aware that the pandemic now pervading the nation must be dealt with, but without violating the public’s constitutional rights. Not only is there a lack of procedural due process with respect to the Travel Ban, but the above examples show that these travel regulations are not narrowly tailored to achieve the government’s purpose.

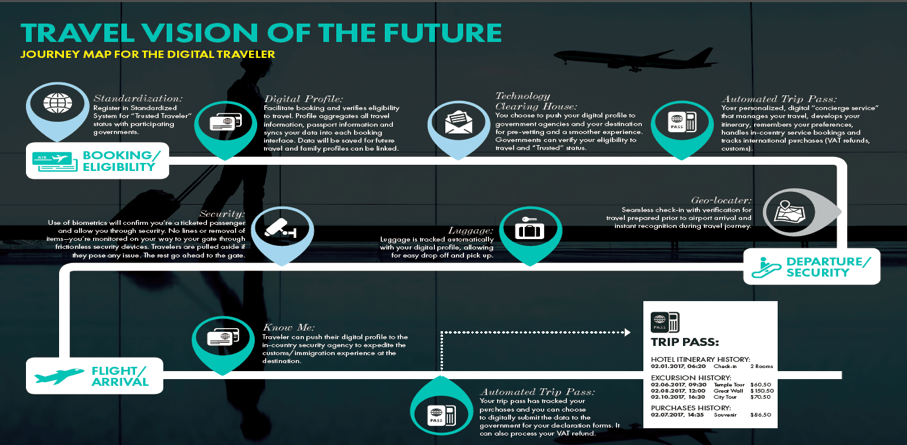

The trauma of 9/11 led to a tendency, all too pervasive even today, to treat air travel as per se more dangerous than other modes of travel and thus as warranting restrictions in the name of “security”, even though it was and remained the safest mode of travel.

We fear that the trauma of the COVID-19 pandemic will lead to a similar impulse to equate the risk of infection with the risk of disease, and to impose restrictions on travel on this basis. We are especially pleased, therefore, that Judge Bertelsman recognized that travel — in a closed private vehicle, for example — carries in itself little risk of disease transmission, and that restrictions on travel do not necessarily serve to restrict the spread of disease.

We hope that this common-sense analysis, based on recognition of the right to travel and strict fact-based scrutiny of proposed travel restrictions and the justifications for them offered by government authorities, is followed by other judges.