How airline reservations are used to target illegal searches

One of the most detailed pictures to date of how the US government uses airline reservations to target illegal searches is provided by documents released recently by the US government as part of an agreement to settle a lawsuit brought by David House, an activist with the Pvt. Manning Support Network.

Mr. House was detained and searched and had his electronic devices confiscated and copied by DHS personnel at O’Hare Airport as he was re-entering the US after a vacation in Mexico in 2010.

The government learned of Mr. House’s travel plans through their systems for real-time monitoring and mining of airline reservations:

The ACLU analysis of the documents released to Mr. House, and reports by the New York Times and the Associated Press, focus on the DHS seizure and copying of the data from Mr. House’s electronic devices. An article in Mother Jones highlights the technical ineptness of the government’s attempts to analyze the data seized from Mr. House. (It took DHS “experts” more than a month, for example, to realize that a portion of the data dump from Mr. House’s netbook was a Linux partition.)

But as discussed below, more is revealed by these documents about DHS access to, and use of, airline reservations.

The documents released to Mr. House may also help explain how David Miranda, the domestic partner of journalist Glenn Greenwald, was detained and searched last month while changing planes at Heathrow Airport in London.

And in that context, they may also suggest an explanation for why Mr. Miranda was detained and searched in the UK, and Mr. House in the US, but Mr. Greenwald himself has not been detained or similarly searched when he travels to the US.

David House is a US citizen, human rights activist, and computer scientist at MIT. He lives in Cambridge, MA, and the lawsuit that led to the latest release of the DHS documents was brought on his behalf by the ACLU of Massachusetts:

The ACLU lawsuit charges that the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) singled out House at the border solely on the basis of his association with the Bradley Manning Support Network, an organization created to raise funds and support for the legal defense of Pfc. Bradley Manning, a soldier charged with leaking a video and documents relating to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan to the WikiLeaks website….

In November 2010, DHS agents stopped House at O’Hare International Airport as he returned from a vacation in Mexico and questioned him about his political activities and beliefs. DHS officials then confiscated his laptop computer, camera and a USB drive and did not return them to House for nearly seven weeks – after the ACLU sent a letter demanding their return. House’s detention and interrogation by DHS officials and the seizure of his electronic papers and personal effects had no apparent connection with the protection of U.S. borders or the enforcement of customs laws. Seven months later, House has not received an explanation of why his property was confiscated or what the government has done with the information downloaded from the devices.

The government’s first response to the lawsuit was to argue that it didn’t need to provide any basis for suspicion that Mr. House had violated or had evidence of any violation of any law. DHS lawyers claimed that international travel provides, in and of itself, sufficient Constitutional basis for detention and search of international travelers and the search, seizure and copying of the digital contents of their belongings.

In a preliminary ruling, the District Court found that the government’s authority for border searches is not unlimited, and that the court retained the authority to review the Constitutionality of the search and of the subsequent retention and use of information seized at the border.

Following this ruling, the DHS agreed to a settlement in which it promised to destroy all copies of the data obtained from Mr. House’s netbook, cell phone, and flash drives, and provided some information about how it had targeted Mr. House. In exchange, Mr. House agreed to the dismissal of the lawsuit.

By agreeing to settle the case, the DHS avoided either any new appellate precedent limiting its borders search authority, or any judicial review of the specific basis for its actions with respect to Mr. House. As in other cases, the DHS treated the threat of judicial review of its actions as the ultimate danger to be avoided at all costs, even if that required destroying evidence it had previously claimed was vitally needed.

Last week the documents released by the DHS pursuant to the settlement were finally made public. They show that on July 8, 2010, the DHS Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) division created a “lookout” for Mr. House in a DHS database called “TECS” (originally the “Treasury Enforcement Communications System”).

TECS was the first pre-DHS database of Federal government logs of international travel. Several other “systems of records” (a term of art used in the Privacy Act) about travelers, including the Automated Targeting System (ATS) and DHS copies of PNR data (airline reservations) were originally considered part of TECS. The TECS file for an individual traveler typically includes a log of their border crossings (with record locators that serve as pointers to their PNR data ) and free-text notes on anything that customs and immigration inspectors thought warranted inclusion in the traveler’s permanent file.

Entries in the TECS border-crossing log are typically created either when a traveler crosses a border, or when an airline or other common carrier sends DHS “Advance Passenger Information” (API).

In Mr. House’s case, an alert was generated by TECS four days before his scheduled flight. That’s probably when American Airlines made its first API transmission to DHS for the flight on which Mr. House was booked to depart the U.S., although it’s possible that API transmissions began earlier but that this was the earliest API transmission for this flight which included a (newly made) reservation for Mr. House.

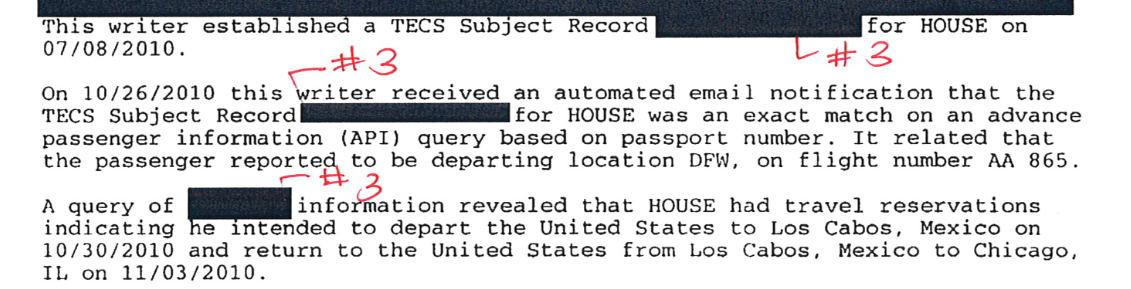

The ICE investigator reported that:

On 10/26/2010 this writer received an automated email notification that the TECS Subject Record [redacted] was an exact match on an advance passenger information (API) query based on passport number. It reported that the passenger reported to be departing location DFW, on flight number AA 865.

API data includes each passenger’s name, date of birth, passport or other document number, and the flight on which they have reservations to travel to, from, via, or overflying the US. But unlike a passenger name record (PNR), which includes a traveler’s entire itinerary in a single record, an API message only links an identity to a single flight, and only shows the first destination outside the US of a departing flight, or the last embarkation point outside the US of an arriving flight. It’s impossible to tell from an API record for a flight departing the US whether a passenger on that flight is actually making onward connections to some other place, or whether, when, or on what flight arriving at what airport they intend to return.

So the ICE investigator had to look up House’s PNR data to find out his full itinerary:

A query of [redacted] information revealed that HOUSE had travel reservations indicating he intended to depart the United States to Los Cabos, Mexico on 10/30/2010 and return to the United States from Los Cabos, Mexico to Chicago, IL on 11/03/2010.

The report as released by DHS is in a monospaced font, and the redacted word(s) in this sentence appears to be seven characters long. CBP receives copies of PNR data and stores them in its ATS database. But “PNR” or “ATS” (or “API, APIS, or TECS) are all too short for the redacted string of text. “Airline” would fit, though:

The implication is that rather than search its own ATS database of copies of PNR data, the ICE investigator searched the airline’s own internal PNR database, using the DHS root access to the Sabre computerized reservation system (CRS) used by American Airlines. That was probably easier than searching ATS because the way DHS “ingests” PNR data from CRSs into ATS leaves the data less well indexed in TECS and ATS than it was (and still is — the airline sends DHS a copy, but of course retains the PNR data itself) in the CRS.

Notably, there’s nothing to indicate that the ICE investigator needed approval from a supervisor to go into Sabre, or tried some other source of PNR information (e.g. the internal ATS database of DHS copies of PNR data) first. Root access to Sabre was apparently at his fingertips, and his use of it warranted no special comment and no recording of compliance with any authorization protocols. It was a routine tool for him.

Presumably, the word “airline” was redacted to avoid calling attention to DHS root access to Sabre, or to the fact that PNR data was used for purposes entirely unrelated to aviation security.

(Please leave us a comment if you have an alternate suggestion for how to fill in the seven-character blank.)

A similar process was probably followed to target David Miranda with a US and/or UK “lookout”, and then to identify from API and/or PNR data when he had reservations to change planes in London en route home from Berlin to Rio de Janiero.

The unanswered question about Mr. Miranda’s detention, interrogation, and search is whether he was targeted by the US, the UK, or both.

A White House spokesperson said (video here) that the US government had been told in advance that Mr. Miranda’s detention might happen. Both parts of that statement (“in advance” and “might”) are revealing.

Mr. Miranda might have had to show his passport at Heathrow while changing planes. But by the time Mr. Miranda showed his passport at Heathrow, it would have been too late for UK authorities to notify the US in advance, nor would there have been any doubt as to whether Mr. Miranda would be detained.

The US statement supports the thesis that Mr. Miranda had been flagged some time earlier in one of the systems that scans API entries, and that the US was alerted once Mr. Miranda was identified from API data transmitted by British Airways (perhaps confirmed from PNR data) as having reservations for flight connections through London, most likely a few days later. At that point, the authorities wouldn’t have been sure if Mr. Miranda would actually be on those flights. So the alert to the US would logically have been of what “might” happen.

In the same press conference, the White House said that the “decision” to detain Mr. Miranda was made by the UK, not the US, and that the US did not “request” that the UK detain Mr. Miranda. But that begs the question of what role the US might have played in “advising” or “suggesting” that the UK detain him.

The UK has the capability to have detected Mr. Miranda’s travel plans without US help, assuming that the UK had enough information, such as Mr. Miranda’s Brazilian passport number, to identify him from API and/or PNR data.

The UK requires international airlines to supply API data on passengers with reservations for flights to the UK — even those like Mr. Miranda who are booked on flights from within the EU.

The UK has its own National Border Targeting Centre (NBTC), which mines API and PNR data to target selected passengers for detention, interrogation, search, or orders to airlines to deny boarding. (Relocated to Manchester from Heathrow in 2010, the NBTC and the associated “e-Borders” project were originally contracted out to Raytheon. Raytheon was later fired after questions were raised about cost overruns, but is suing the UK government for half a billion pounds for breach of contract.)

However, the reverse is also true: The US could have detected that Mr. Miranda had reservations on a flight from Berlin to London, even without assistance from the UK. ATS records we have obtained from the DHS include PNR data for separately ticketed flights within the EU, not connecting to or from any flights that touch the US, operated by airlines that don’t fly to the US. (See page 23 of these slides from a presentation we gave earlier this year at the Cato Institute and on C-SPAN.) These records could only be obtained by the DHS if it has — as it does — geographically unrestricted root access to the CRSs used by these airlines and their agents.

Regardless of whether it was based on airline data accessed by the US or the UK, the detention of Mr. Miranda could have been initiated by the US government, even if the “decision” was made by the UK government.

Documents obtained from the German government by Andrej Hunko, a member of the German national legislature, show that the US has numerous “advisors” posted within Europe, including at major airports. According to Mr. Hunko’s report, which was first published in English here on PapersPlease.org two years ago:

394 employees of various DHS departments and agencies are deployed in the EU, including US Customs and Border Protection (CBP), US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the Transportation Security Administration (TSA), the US Secret Service (USSS), the US Coast Guard (USCG), the US Citizenship and Immigration Service (USCIS), the DHS Office of Policy, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center (FLETC) and the National Protection and Programs Directorate (NPPD)….

No fewer than 75 of the 394 persons working for the Department of Homeland Security are operating in Germany, chiefly in the realms of border surveillance, customs and transport. I received little specific information regarding the airports and sea ports where staff employed by the DHS are working, but Frankfurt, Hamburg and Bremerhaven are certainly among them.

Mr. Miranda’s flight originated in Berlin, which is likely to be another of those airports where DHS advisors are based. And while Mr. Hunko’s inquiries concerned DHS personnel and their activities in Germany, and no similar inquiries have been directed to the UK government, it would be surprising if the DHS didn’t have at least as large a presence and as close relationships with local authorities at Heathrow (and/or at the the NBTC in Manchester) as at Frankfurt Airport.

So we don’t yet know whether the idea of seizing Mr. Miranda originated with US or UK authorities.

The other remaining question is why, if the US government had the ability and authority to seize Mr. House and his data (without a warrant or any basis for suspicion that it was willing to articulate to a court), the US didn’t do the same with Mr. Greenwald on one of his trips back to the US, but instead went after Mr. Greenwald’s partner, Mr. Miranda, while he was in transit through the UK.

Mr. Greenwald is a US citizen, while Mr. Miranda is Brazilian. Was the US uncertain of its authority to detain and seize data from a US citizen? Given its treatment of Mr. House, who like Mr. Greenwald is a US citizen, that seems unlikely (unless the US had really learned a lesson from the initial ruling in Mr. House’s lawsuit, which seems even more improbable).

Perhaps the US and/or UK authorities thought, for whatever reason(s) that Mr. Miranda would be easier to intimidate than Mr. Greenwald? That’s possible.

Another explanation for the choice of venue in the UK rather than the US might be a relatively little-known US law, Title 42 US Code Section 2000aa. This law would have protected much of Mr. Greenwald’s data, and possibly Mr. Miranda’s, against search by US officials, but probably wouldn’t have protected Mr. House.

42 USC 2000aa is described as the “Privacy Protection Act of 1980”, but it’s not a general privacy protection law. Rather, its protections are limited to “work product materials” related to possible publication:

Notwithstanding any other law, it shall be unlawful for a government officer or employee, in connection with the investigation or prosecution of a criminal offense, to search for or seize any work product materials possessed by a person reasonably believed to have a purpose to disseminate to the public a newspaper, book, broadcast, or other similar form of public communication, in or affecting interstate or foreign commerce….

Notably, this law protects anyone “reasonably believed to have a purpose to disseminate to the public a … form of public communication”, regardless of the form of publication or whether the person is employed as, or fits any other definition of, a “journalist”. If you take photos with your camera or smartphone with the idea that you might post some of them on your Facebook page, for example, those photos are protected from search or seizure. It doesn’t matter whether you are a US citizen or a professional journalist, or whether any or all of those photos would necessarily have been published. While the Privacy Protection Act doesn’t have as strong protections for covered individuals and material as the proposed “shield laws” for journalists currently being considered by Congress, it protects a much wider range of individuals and material.

Mr. House was reportedly involved in political activities in support of Pvt. Chelsea Manning, but he hasn’t claimed that any of the data seized from him was intended for publication. Mr. Miranda, on the other hand, was seized precisely because authorities hoped he would be carrying work product materials related to Mr. Greenwald’s reporting. Regardless of Mr. Miranda’s citizenship, such a search or seizure carried out by US authorities would have violated the Privacy Protection Act. This could be why he was targeted in the UK, where US “advisors” would have plausible deniability as to their role in “suggesting” that he be seized and all the data he was carrying be copied.

The Privacy Protection Act has exceptions, including one for certain searches at borders and airports (42 USC 2000aa-5), but that exception has two crucial limitations:

First, the exception applies only at international borders and other international points of entry such as international airports. There is no general exceptions to the Privacy Protection Act for all “administrative searches” or even all airport searches. The “Notwithstanding any other law” clause of the Privacy Protection Act, the explicit exception for certain searches at international points of entry, and the absence of any similar explicit exception for searches at domestic airports or any other administrative searches, makes clear that the Privacy Protection Act prohibits the search or seizure at TSA checkpoints for domestic US flights, without probable cause, of publication work product materials.

Second, the exception to the Privacy Protection Act at international points of entry is limited to searches conducted “in order to enforce the customs laws of the United States.” International airport and border searches conducted for any other purpose — including enforcement of laws related to aviation, terrorism, espionage, or unauthorized disclosure of classified documents — are subject to the restrictions in the Privacy Protection Act.

Government agents, unlike members of the public, can often get away with illegal actions if they can plausibly claim that they didn’t know that what they were doing was illegal. And we doubt that TSA checkpoint staff, customs and immigration inspectors, and local law enforcement officers who provide the “muscle” for them at airports and borders are trained in the Privacy Protection Act. They probably assume that what they think is a general airport and border exception to the Fourth Amendment includes an exception to the Privacy Protection Act (if they have even heard of this law).

If you plan to invoke the Privacy Protection Act, you may want to carry a copy with you (you can fit this 3-page PDF on one letter-sized sheet if you print it double-sided, two pages to a side) and keep a copy, perhaps as a “readme” file, in the root and/or user data directories of each of your electronic devices. And you should tell any US government agents who try to seize or search your data that you have work product materials and an intention of disseminating information to the public, so they can’t later plead that they were unaware of the law governing their actions and that their illegal search and/or seizure was an innocent mistake.

“Lookout” would fit the 7 letter redaction. Also, it could be a proprietary name of a government program.

Pingback: How airline reservations are used to target illegal searches – IzaakNews

It seems like it’s trivial to obtain someone for their data at this point. Shouldn’t the NSA already have all of that info?

Coming here and finding white text on a black background is too unpleasant. Good-bye!

Link to actual PPA: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/42/2000aa

So, what the US government is doing is unveiled by coincidence, because of all this Snowden/PRISM stuff (because now people are watching more exactly on these topics).

BUT i guess all governments are supporting actions like this, if not explicitly, then implicitly.

When you arrive in Heathrow and change planes for another international flight, you do not go through UK immigration and you do not show your passport. If your airline has issued a boarding pass in the originating country, you only have to show your passport to identify yourself when boarding your connecting flight. If your airline has not issued you a boarding pass for your new flight, or if you are traveling on another airline, you have to present your passport when you check in at Heathrow. This is done without exiting the secure area. You can of course go through UK immigration and come back in but there is usually no reason to unless you have a 12 or 24 hour layover.

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » What you need to know about your rights at the airport

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » How the NSA obtains and uses airline reservations

Update: More recent details on DHS personnel in Germany and their role in no-fly “recommendations” (German government responses to written questions by Bundestag member Andrej Hunko, December 27, 2013):

http://dip21.bundestag.de/dip21/btd/18/002/1800244.pdf

‘Why Have You Gone to Russia Three Times in Two Months?’ — Heathrow Customs Agent Interrogates Snowden Lawyer

(by Kevin Gosztola, Firedoglake.com, February 16, 2014)

http://dissenter.firedoglake.com/2014/02/16/why-have-you-gone-to-russia-three-times-in-two-months-heathrow-border-agent-interrogates-snowden-lawyer/

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » “Jetsetting Terrorist” confirms DHS use of NSA intercepts

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » Does an airline have the “right” to refuse service to anyone?

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » “Secondary inspection” used as pretext for airport drug searches

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » Laura Poitras sues DHS et al. for records of her airport detentions and searches

Pingback: “KOSTENLOSES W-LAN IST SEHR SEHR TEUER”: SNOWDEN | subito

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » Searches at airports and US borders

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » Palantir, Peter Thiel, Big Data, and the DHS

Pingback: “Border control” as pretext for drug dragnet | Papers, Please!

Pingback: DHS continues to target traveling journalists for illegal searches – Papers, Please!

Joint report by Offices of the Inspectors General gives additional examples of how TECS alerts operate and are used:

https://unicornriot.ninja/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/s1404_0-bostonbombings.pdf

Pingback: FBI enlists reservation services to spy on travelers – Papers, Please!

Pingback: “Put them on the no-fly list!” – Papers, Please!

Pingback: No-Fly Lists – Nazi-Like Travel Tyranny – Liberty Forecast Blog

Pingback: Expanding travel policing beyond no-fly lists (and the Fourth Amendment) – Papers, Please!

Pingback: 9th Circuit to review secrecy of CRS surveillance – Papers, Please!

Pingback: Sabre and Travelport help the government spy on air travelers – Papers, Please!

Pingback: The #NoFly list is a #MuslimBan list – Papers, Please!

Pingback: Germany follows US lead in misuse of airline reservation data – Papers, Please!

Pingback: 9th Circuit upholds secret US monitoring of foreign airline reservations – Papers, Please!

Pingback: Border and airport searches for “privileged” information – Papers, Please!

Pingback: DHS uses travel as pretext for search of researchers and journalist – Papers, Please!

Pingback: Customs officers need a warrant to search your cellphone at JFK – Papers, Please!