Public/private partnerships for financial surveillance

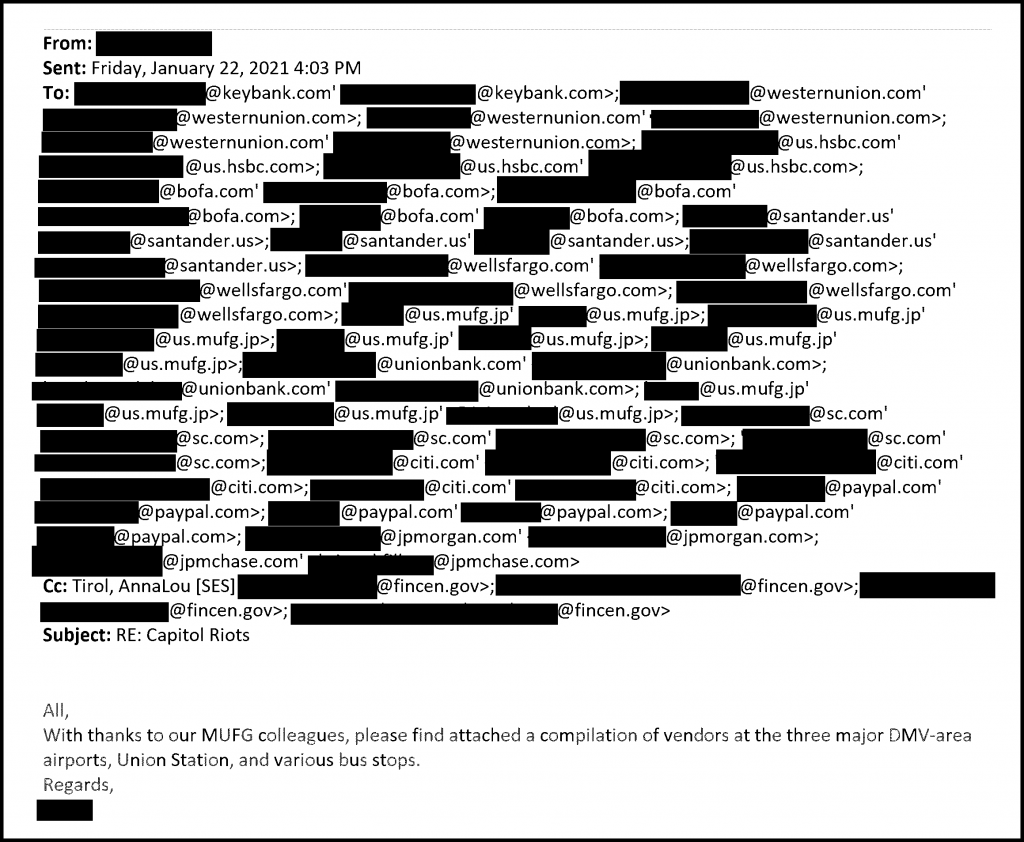

[Email from the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) of the US Department of the Treasury to some of its banking industry partners forwarding list prepared by Mitsubishi United Financial Group (MUFG) of vendors at DMV (DC, Maryland, and Virginia) airports, train stations, and bus stops, to target reporting of purchases at these locations as “suspicious” .]

[Email from the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) of the US Department of the Treasury to some of its banking industry partners forwarding list prepared by Mitsubishi United Financial Group (MUFG) of vendors at DMV (DC, Maryland, and Virginia) airports, train stations, and bus stops, to target reporting of purchases at these locations as “suspicious” .]

The House Committee on the Judiciary and its Select Subcommittee on the Weaponization of the Federal Government have released a ground-breaking report on their investigation of what they describe — accurately, we think — as “the coordination between Big Banks and Big Government” in financial surveillance.

The Judiciary Committee and Subcommittee’s latest report on financial surveillance as well as their earlier interim report on the same issue are part of their broader inquiry into the investigative tactics used in the aftermath of the storming of the US Capitol on January 6, 2021.

Partisan criticism of the Weaponization Subcommittee may lead to some skepticism or dismissal of its report and recommendations. But that would be a mistake, regardless of what anyone thinks about the Weaponization Subcommittee in general. The report is thoroughly researched and its sources are well documented. It’s based on interviews with witnesses from goverment agencies and the banking industry and tens of thousands of documents provided in response to Congressional subpoenas.

The report on financial surveillance uses the post-January 6th investigation only as a case study. The practices it reports on could have been, and still could be, used against any of us, regardless of party or affiliation (if any). They shouldn’t be used against anyone, even the most stigmatized individuals and groups. What we allow to be done to our enemies, or anyone’s enemies, could be done to any of us. The report deserves bipartisan public attention and calls for bipartisan action by Congress.

As we’ve noted in surveying what’s likely to lie ahead in demands for ID and ID-based surveillance and control of our real-world and virtual movements and activities, it’s all too easy and all too common for otherwise-principled civil libertarians to allow their distaste for particularly reviled individuals to blind them to the bad precedents being set by the investigative and prosecutorial tactics used against those stigmatized defendants.

We can’t afford to be sanguine about violations of anyone’s rights. The government’s response to the events of January 6, 2021, was a textbook example of the way that unsympathetic defendants are exploited to expand the norms of permissible and publicly-tolerated investigative and prosecutorial practices that can later used more widely.

After January 6th there were misguided calls to add everyone involved in the storming of the Capitol (and perhaps also anyone suspected of possibly having been involved) to the million-and-a-half names already on the US government’s no-fly list — by summary, secret, extrajudical administrative action. It’s unclear whether, or to what extent, that was done. That remains an open question, as does the larger question of how no-fly decisions are made. We hope that the Weaponization Subcommittee and the Subcommittee on the Administrative State will look into these questions during the next session of Congress.

Suspects were targeted for prosecution after January 6th based on what may have been the most extensive use to date in any single investigation of geofence warrants for cellphone location data. Those general warrants were used not to obtain evidence pertaining to individuals who there was already probable cause to suppect of crimes, but to trawl through records of hundreds of millions of innocent cellphone users to find individuals to place under suspicion based on where their cellphones were logged by Google as having been on that day. Challenges to the Constitutionality of these general warrants for dragnet searchess were all — so far as we can tell — dismissed by the judges hearing these cases.

But that’s not all. The latest Judiciary Committee report shows how logs of routine, entirely legal, financial transactions were subjected to warrantless scrutiny and data mining by banks and financial services providers collaborating with government investigators, and used as the basis for placing individuals under suspicion.

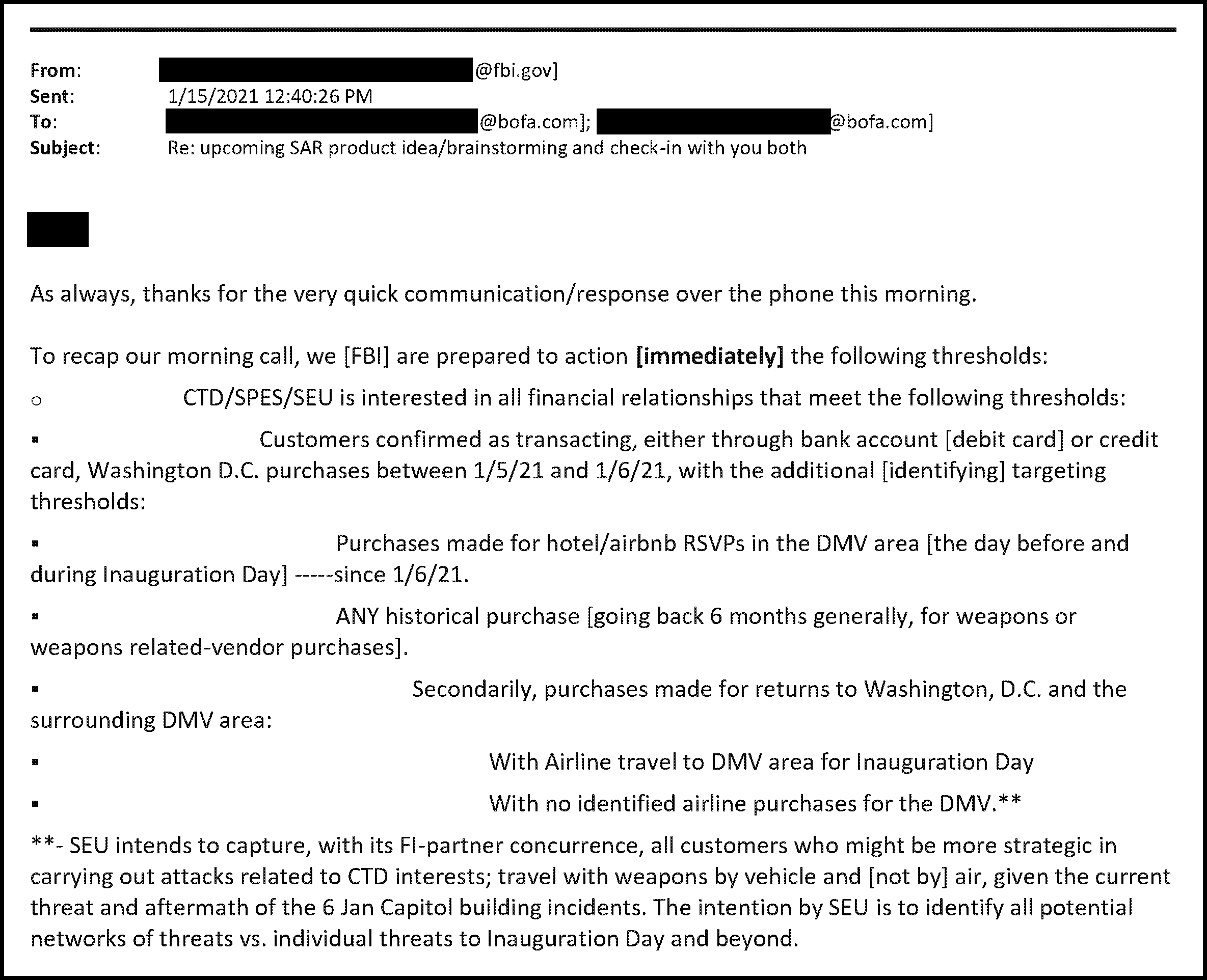

The FBI encouraged banking companies to “voluntarily” submit Suspicious Activity Reports (SARSs) to the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), the police division of the Department of the Treasury. These SARs were used to finger to FinCEN as “suspicious” anyone who had engaged in such mundane activities as taking money out of an ATM, buying a meal at an airport, or paying for a hotel or AirBNB anywhere in the DMV (DC, Maryland, and Virginia) area on January 6th or the days before or after:

To be clear: these transactions were, in and of themselves, entirely legal, and weren’t in and of themselves in any way suspicious. They didn’t create probable cause to believe that each such individual was likely to have committed any crime, and they wouldn’t have provided sufficient basis for the issuance of a search warrant. These SARs were used not to investigate people who were already suspected of crimes, but to identify new individuals to be extrajudically placed under suspicion and investigated without probable cause.

Once submitted to FinCEN, these SARs are available for individual search and retrieval by tens of thousands of government agents, without the need to apply for a warrant. SAR data is also exported in bulk by FinCen for import into other agencies’ data mining systems.

All of this was done pursuant to the Bank Secrecy Act, which turns out to be a law to protect the secrecy of public and private financial surveillance rather than a law to protect the secrecy of bank customers’ private banking and purchasing activities, as witnesses testified to the Weaponization Subcommittee at its hearing on this issue in March 2024.

The Judiciary Committee report describes the way it works as follows:

The FBI has manipulated the Suspicious Activity Report (SAR) filing process to treat financial institutions as de facto arms of law enforcement… While at least one financial institution requested legal process from the FBI for information it was seeking, all too often the FBI appeared to receive no pushback….

The reporting requirements of the Bank Secrecy Act turn financial institutions into confidential informants that are required to secretly report Americans’ financial activities to the federal government. Enacted by Congress in 1970, the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA)…. is primarily enforced by the Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN)…. Pursuant to the BSA and other anti-money laundering laws, covered financial institutions operating in the United States—like banks—are required to file certain reports, such as Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs)… with the federal government reflecting their customers’ information and their financial activities…. [T]he BSA “requires that a bank or other financial institution file a SAR whenever it identifies ‘a suspicious transaction relevant to a possible violation of law or regulation.’”…

The BSA regime creates strong incentives for financial institutions to over-file SARs about American citizens—at the cost of Americans’ financial privacy….

In addition to the voluntary filing option, financial institutions have a further incentive to over-file because failing to file a SAR can result in large monetary penalties. As a consequence, financial institutions often file defensively, even when there is little reason to do so. This dynamic is compounded by the BSA’s broad grant of immunity which protects “[a]ny financial institution that makes a voluntary disclosure of any possible violation of law or regulation to a government agency.” Financial institutions are also placed under a de facto gag order prohibiting the revelation of “any information that would reveal that the transaction has been reported.” Viewing this framework together, financial institutions frequently err on the side of over-filing.

Banks and other financial services companies are thus incentivized, through the threat of Federal sanctions, to take actions against individuals for which the government would have insufficient legal basis or no legal basis at all. This resembles the carrier sanctions that incentivize airlines — acting as outsourced de facto immigration and asylum judges of first and last resort — to deny passage to would-be travelers who airline staff think might be denied admission on arrival, but who are subject to no legal order of exclusion.

Airlines have been deputized to carry out immigration and asylum denials. Banks have been deputized to carry out warrantless searches. This privatization and outsourcing of judicial decision-making is unconstitutional. As with the public/private travel surveillance partnership between the government and the airline industry, this public/private financial surveillance partnership should be put to an end — now.

The Judiciary Committee report concludes with the following recommendations:

Under the current BSA framework, financial institutions are required to act as confidential informants on their customers, reporting them to the federal government without any recourse or notice available to the customer. Congress could amend the BSA to require that banks, after a certain period of time, give notice to the customer that a SAR was filed, provide a justification, and offer an opportunity for the customer to respond to allegations they engaged in “suspicious activity.” Other reforms propose establishing “a private right of action for Americans and financial institutions harmed by illicit government activity.”

Finally, Congress could restore Fourth Amendment protections to Americans’ financial records. In order to end warrantless surveillance, Congress could require a warrant before law enforcement can gain access to Americans’ private financial information. Senator Mike Lee’s Saving Privacy Act proposes bolstering the warrant requirement under the Right to Financial Privacy Act of 1978. Americans should not have to choose between having a bank account and worrying that the federal government may have warrantless access to their personal financial decisions and other revealing details about their pattern of life, interests, faith, politics, and more.

Along with its latest report on what is still a continuing Congressional investigation, the Judicary Committee released an appendix containing more than 700 pages of interview transcripts and other evidence:

- Financial Surveillance in the US: 1st interim report (March 6, 2024)

- Financial Surveillance in the US: 2nd interim report (December 6, 2024)

- Appendix to 2nd interim report

- BSAAG (Bank Secrey Act Advisory Group) white paper, “Brick & Mortar to Bits & Bytes” (included in appendix to 2nd interim report)

The most interesting item in the appendix to the latest Judiciary Committee report is this previously-undisclosed white paper on digital ID produced by the public/private Bank Secrecy Act Advisory Group (BSAAG). FinCen is currently soliciting nominations for membership in BSAAG, but civil liberties organizations and advocates don’t qualify.

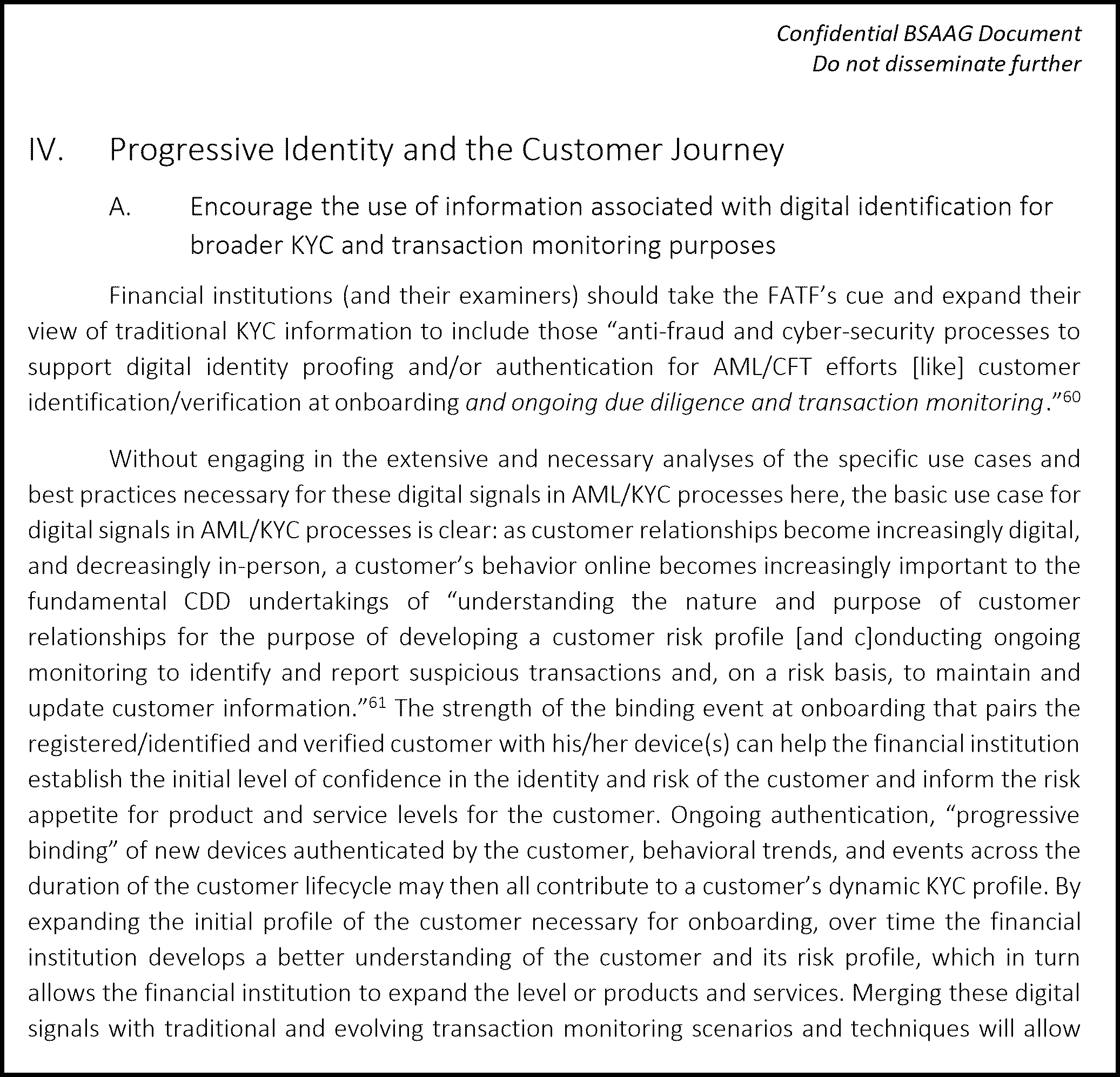

The BSAAG white paper lays out a dystopian vision for national digital ID, “bound” to a smartphone or other device, as a tool for transaction monitoring and surveillance.

Identifying individuals, or requiring them to identify themselves, is the key enabler for tracking and logging their activities and using those logs to profile them and make predictive, pre-crime decsions about whether they are risky or suspicious.

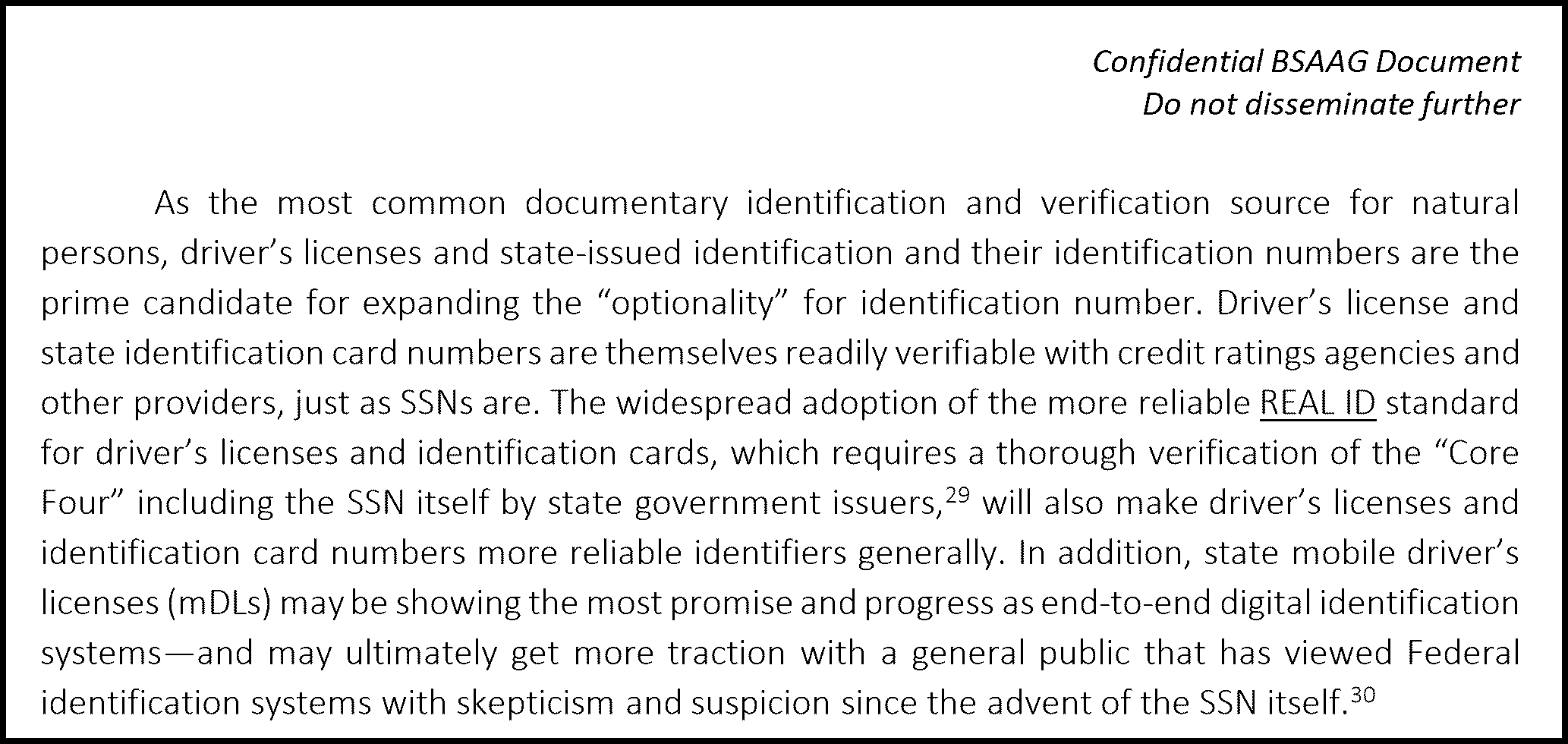

BSAAG notes the longstanding public opinion against national ID, but sees a way around that through a national ID system that is Federally overseen and standardized, but operated on a distributed basis by state driver’s license agencies that are less obviously Big Brother-like than Federal law enforcement agencies:

BSAAG sees the national system of REAL-ID mobile driver’s licenses as the most promising path to an “end to end” digital ID system that would enable the tracking it wants:

And the BSAAG looks forward to collaboration between Federal and state agencies, technology providers, and the financial services industry to realize this vision:

As the Judiciary Committee report summarizes it, “BSAAG… is advancing plans that would require Americans to have a digital identification to access financial services… and working towards even closer coordination between financial institutions and federal law enforcement.”

We are grateful to the Judiciary Committee and the Weaponization Subcommitteee for exposing what’s been happening and where this is headed. Now it’s up to Congress to act — and up to us to resist demands for ID, even in commercial settings, that can be secretly reported to law enforcement agencies and used to track and target us.

Pingback: Government identification as a service - net.wars

Pingback: UK “Electronic Travel Authorization” sets a bad example – Papers, Please!

Pingback: FinCen demands reporting of cash transactions over $200 – Papers, Please!