FBI enlists reservation services to spy on travelers

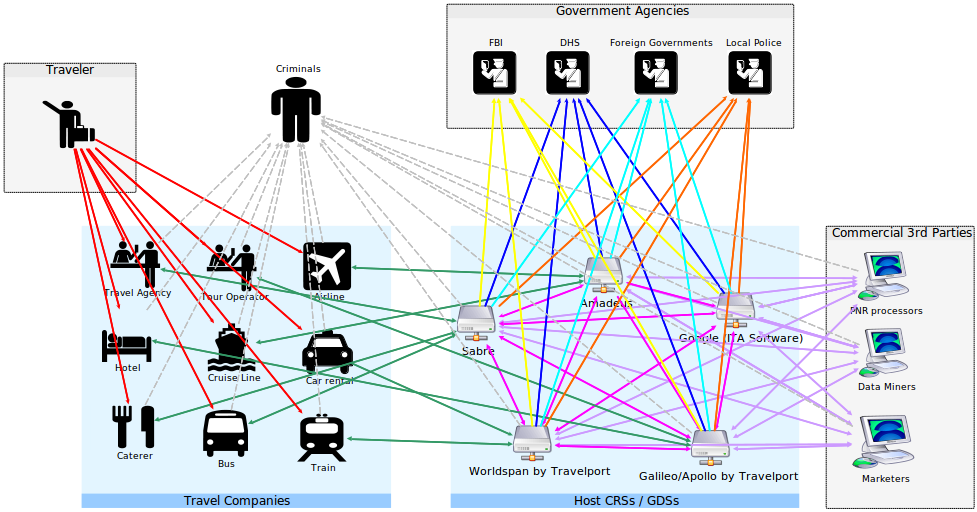

[The role of CRSs in the travel data ecosystem and government access to airline data. Slide from Identity Project presentation on C-SPAN, April 2, 2013.]

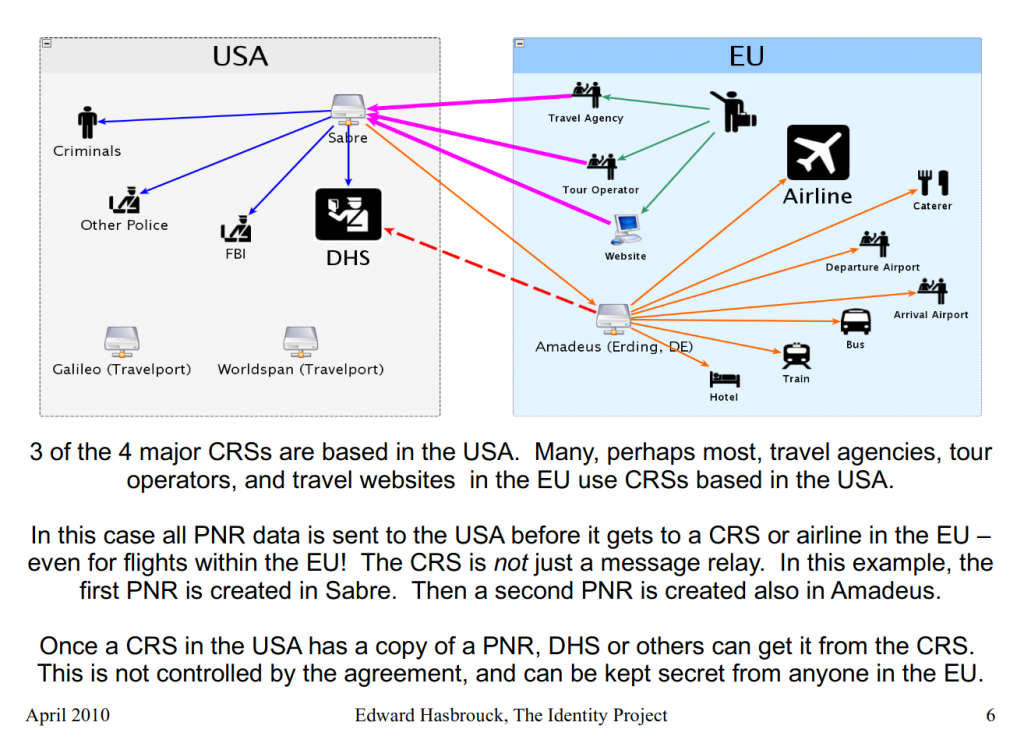

[The role of CRSs in the travel data ecosystem and government access to airline data. Slide from Identity Project presentation on C-SPAN, April 2, 2013.]

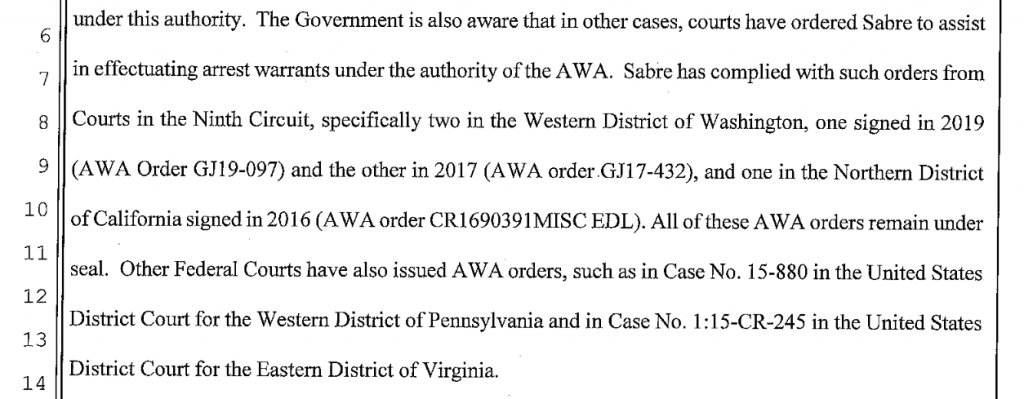

A report by Thomas Brewster published yesterday by Forbes discloses that the FBI has used court orders issued under the “All Writs Act” (AWA) to order operators of computerized reservation systems (CRSs) to provide weekly reports on any new reservations made by specified persons of interest, for periods of as long as six months at a time.

The article in Forbes includes a copy of one of these orders issued to Sabre, which mentions, by way of legal precedents, some other such orders issued to Sabre:

Forbes also describes a similar All-Writs Act order issued to Travelport, another of the three major CRS operators.

Who are these CRSs? What are we to make of these court orders? And is there anything really surprising about the newly-revealed All Writs Act orders to Sabre and Travelport?

This report in Forbes and these orders aren’t a surprise, but they do provide positive confirmation of (previously suspected) facts about US government activities and US law that may be of considerable significance to challenges to travel surveillance under the laws of other countries including the European Union, Canada, and possibly others.

As we’ve been pointing out for many years, computerized reservation systems (also known as “global distribution systems”) are central to the storage and transmission of airline reservations (and, to a lesser extent, reservations for hotels, rental cars, and other travel services) by and between airlines, travel agencies, other travel companies — and government agencies. Most airlines and almost all travel agencies don’t host their own reservation data (“Passenger Name Records“), but outsource PNR hosting to one of the three major CRS operators: Sabre, Travelport, or Amadeus.

Access to airline, travel agency, and other travel company data through CRSs is often preferred by government agencies because going directly to the CRSs is simpler (there are only three major CRSs and their systems and standards to deal with), more direct (it’s the CRSs that actually host most PNRs, so a request or order to an airine for data would have to be fulfilled by or through the host CRS anyway), and easier to hide from the subjects of surveillance than obtaining data from companies that deal directly with travelers.

For similar reasons, the FBI has also sought and obtained PNR data and other travel records from other companies that aggregate data from multiple CRSs.

The order to Sabre included a “gag order” clause prohibiting Sabre from disclosing the existence of the order to any person or entity except Sabre’s lawyers. That means not only that Sabre was forbidden to reveal the order publicly, or to the person whose travel plans were to be reported to the FBI, but also that Sabre was forbidden to reveal the order to the airline(s) operating flights on which the person of interest made reservations, or to any (offline or online) travel agency that might have been involved in making the reservations.

This isn’t news, and shouldn’t be surprising. We’ve talked about exactly this possibility many times, including in testimony at a hearing before the European Parliament in 2010 and in an FAQ about PNR data prepared during the debate in the European Parliament in 2012 on the (in)adequacy of legal protection for PNR data transferred to the US.

What’s changed is that the example in the slide below from our 2010 testimony in Brussels, using Sabre as an example, is an example of something we now know has happened, not merely something we have long known could happen:

[Slide from testimony by Edward Hasbrouck of the Identity Project at a hearing before the LIBE Committee of the European Parliament, Brussels, April 8, 2010.]

[Slide from testimony by Edward Hasbrouck of the Identity Project at a hearing before the LIBE Committee of the European Parliament, Brussels, April 8, 2010.]

The gag order included in the All Writs Act order to Sabre means, of course, that neither the airline, travel agency, or individual has any opportunity to challenge the government’s application for such an order, even if the airline or travel agency were inclined to do so.

The gag order issued to Sabre also matters because privacy norms incorporated into data protection laws in many other countries (although not the US) require companies to disclose to individuals, on request, to whom, or to which third parties (including government agencies), personal data has been transferred. But as the order issued to Sabre conclusively proves, data sent to a CRS in the US can be passed on to US government agencies without the knowledge of the airline, travel agency, or individual to which it pertains. CRSs don’t keep access logs for PNRs, so in such a case, the airline (and any travel agency involved in the PNR) is unable to comply with its obligation under the laws of any country where it operate that requires such an accounting of disclosures.

It’s hard to avoid the conclusion that outsourcing PNR hosting to a CRS based in the US such as Sabre or Travelport, and possibly also to one such as Amadeus with servers in the US, is inherently incompatible with compliance with these other countries’ laws as long as US law permits this sort of government access and gag order.

The use of the All Writs Act (more on that below) is less significant than the use by the US government of an order to a CRS in the US to obtain information about a non-US person, not believed to be located in the US, pertaining to reservations on flights that might have included flights on non-US airlines between points outside the US, all without any possibility of notice to, or objection by, that non-US person or those airlines.

This is directly related to the issues in ongoing litigation in Europe over transfers of personal data from the European Union to companies or servers in the US. A key factor in yesterday’s long-anticipated finding by the Court of Justice of the European Union that contracts between private entities in Europe and the US cannot insure protection of personal data transfered to entities or servers in the US is that the US government can obtain that data from those US entities without any possibility for the individuals to whom that data pertains to obtain redress through US courts. Now we have proof that the US government is, in fact, obtaining PNR data in just these ways.

Ths subject of the order to Sabre is an Indian citizen who the US believed to be living in India and planning to travel to the US. Presumably, the information about this person’s airline reservations which the FBI sought to obtain from Sabre was information collected by an airline office, travel agency, or other ticket sales outlet in India, and then transferred to Sabre’s servers in the US. The FBI is, we now know, using the loopholes and lack of protection in US law to obtain personal information collected in another country and transferred to the US.

There’s no mention in the FBI’s application to the court either of the Indian law applicable to personal information collected in India, or of any contracts between Sabre and its travel agency subscribers or airline hosting customers in India. None of those are relevant, under US law, to the approval of the order to Sabre by US courts.

If Facebook, as the CJEU ruled yesterday, cannot (under EU law) rely on commercial contracts between European and US entities to insure protection for personal information transferred from the EU to the US, neither can airlines, travel agencies, or CRSs.

Questions remain as to why the FBI used the tactic of an application for an order pursuant to the All Writs Act to obtain this data.

Historically, starting long before 9/11, airlines and CRSs have, routinely, provided this sort of data and “coperation” with law enforcement agencies without asking police to show a warrant. Under US law, personal data voluntarily provided to, or obtained independently by, a “third party”, belongs to that third party, who is free to “voluntarily” provide that data to government agents or anyone else.

To put it more crudely, it’s legal under US law for businesses to snitch on their customers, without any need for the “probable cause” the government would need to get a warrant.

After 9/11, when teams of FBI agents showed up at travel companies — probably including Sabre — and stayed for months copying and mining their records, FBI officials later told reporters that they had obtained subpoenas for the information they wanted. But these FBI officials also noted that the law didn’t require them to obtain subpoenas or warrants — a statement that would be true only if travel companies didn’t demand them, and were willing to hand over everything the government asked for, voluntarily.

Have Sabre and Travelport changed the policies according to which they routinely complied with government requests for information about travelers, without asking for warrants? In the past, Sabre, Travelport, and Amadeus have all declined to discuss these policies.

Some internet service providers and other Internet companies publish annual or otherwise periodic “transparency reports” on how many government requests or demands for information about customers or users they have received, and how they have responded. Some Internet companies have challenged both government demands for user data and gag orders about those demands.

So far as we can tell, no airline, CRS, or travel agency has ever published such a transparency report — perhaps because doing so would call attention to the travel industry corporate norm of willing collaboration with police in spying on travelers. Nor, so far as we can tell, has any travel company ever stood up for its customers’ privacy and civil liberties by challenging a government request for information about travelers.

Even without voluntary cooperation by CRSs, the FBI has easier means of access to the information they claimed to be seeking to obtain from Sabre. According to the application for the court order, the FBI had reason to suspect that the subject of a particular arrest warrant might be planning to travel from India, where he lived, to the US. The FBI wanted to find out when and if the subject of the arrest warrant made reservations to travel to the US.

But all airlines operating international flights to, from, or overflying the US are already required to send “Advance Passenger Information” about all reservations for those flights, at least 72 hours in advance or as soon as reservations are made, whichever comes first, to US Customer and Border Protection (CBP). CBP stores this API data in its “TECS” database.

Any law enforcement agency including the FBI can ask CBP to set a “TECS alert” so that as soon as a reservation shows up in the system matching the criteria in the alert (such as the passport number of a person of interest), the agent handling the case will receive an automated email message with the details. Seventy-two hours notice before a flight to the US gives the agency receiving the alert plenty of time to arrange an unwelcoming party to meet them at the airport when they arrive in the US.

The small number of precedents for All Writs Act orders to Sabre (each of which requires the involvement of the US Attorney’s office and a judge), compared with the much larger number of administratively simpler TECS alerts, suggests that All Writs Act requests are made either when the FBI actually wants information (such as reservations for domestic flights or flights entirely outside the US) that wouldn’t be available from API transmissions and TECS, or in the few instances when an inept or poorly-trained FBI agent didn’t get the memo about the availability and simplicity of TECS alerts.

GDSs Decline To Join Major Tech Companies In ‘Transparency Reporting’

(by Jay Boehmer, The Beat, July 30, 2020; subscribers only):

https://www.thebeat.travel/News/GDSs-Decline-To-Join-Major-Tech-Companies-In-Transparency-Reporting-

Pingback: 9th Circuit to review secrecy of CRS surveillance – Papers, Please!

Pingback: Sabre and Travelport help the government spy on air travelers – Papers, Please!

Pingback: Airlines Are Selling Your Data to ICE | Mandala

Pingback: Airlines Are Selling Your Data to ICE