National REAL-ID database replicates problems with FBI rap sheets

Previously unpublished information we’ve recently obtained from the contractor that developed the SPEXS database at the center of state “compliance” with the REAL-ID Act — the national database of drivers license and state ID details that the DHS and supporters of the REAL-ID Act keep claiming doesn’t exist — shed new light on how the system will work.

Unfortunately, these new documents and statements show that SPEXS will replicate many of the worst problems of poor data quality and lack of accountability of the NCIC database used by the FBI to store criminal history “rap sheets” of warrants, arrests, and dispositions of criminal cases: convictions, diversions, withdrawals, dismissals, acquittals, appellate decisions, etc.

Like SPEXS, NCIC aggregates data sourced from agencies in every state, the District of Columbia, and the US territories of Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, American Samoa, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands. The FBI operates the aggregated database, but disclaims any responsibility for the accuracy of the data it stores, indexes, and distributes.

As we noted in our previous post, the FBI has exempted NCIC records from the requirements of the Privacy Act for accuracy, relevance to a lawful purpose, access by data subjects, and correction of errors. That should mean that NCIC records can’t be relied on, but the Supreme Court has ruled that an entry in NCIC provides sufficient legal basis for an arrest.

NCIC is the poster child for the evil consequences of reliance on “garbage in, garbage out” aggregated and unverified data as a basis for government decision-making. Inevitably, NCIC records are riddled with errors. Law enforcement agencies are quick to report arrests and newly-issued warrants to NCIC, but have nothing to gain by ever reporting when charges are dismissed or a warrant is quashed. Who knows when some other police agency might find it convenient to rely on an NCIC record of a long-since-quashed warrant as a basis for authority to arrest and search someone who they would otherwise have to let walk away?

We know from long and bad experience with NCIC just where this leads. Innocent people are arrested every day in every state on the basis of erroneous NCIC records. SPEXS replicates the “garbage in, garbage out” unverified multi-source data aggregation model of NCIC, and will replicate its data quality and accountability problems along with its architecture.

Like NCIC, SPEXS is intended to be relied on as the basis for government decisions, specifically, enforcement of the requirement of the REAL-ID Act that a person may not have more than one valid REAL-ID Act compliant drivers license or ID at a time. We fail to see any valid purpose to this provision of the law. Given that states have different and independent licensing requirements, what harm is done by a person having independently satisfied the requirements to operate motor vehicles in more than one state, and having independently been issued credentials by these several states attesting to this fact? But regardless of the rationale for this law, the justification for the existence of SPEXS is to enable states to refuse to issue a drivers license or state ID to a person if SPEXS shows a record of an outstanding license or ID in any other state or territory for a person believed (according to a secret SPEXS matching algorithm) to be the same person as the applicant.

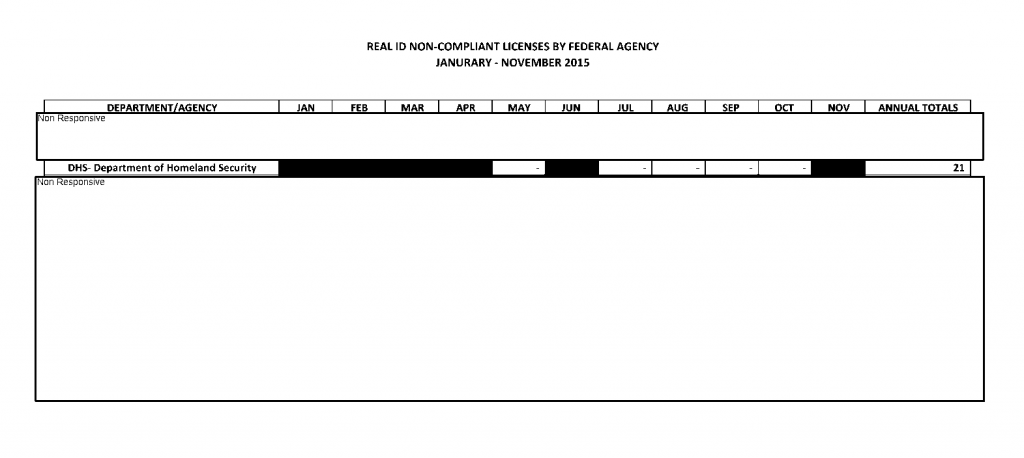

The inevitable outcome is that some people’s applications for new or renewal drivers licenses or state IDs will be denied by state authorities on the basis of erroneous data in SPEXS records. Perhaps they have been mis-matched with a person in another state with the same or a similar name and date of birth. Perhaps an identity thief has used their name, DOB, and Social Security number to get a license or ID in another state. Perhaps they cancelled their license or ID in another state, but that fact wasn’t reported by that state to SPEXS, or the cancellation message wasn’t received by the SPEXS operator or wasn’t properly processed into the SPEXS database. Perhaps the expiration date of their old license or ID was mis-reported or improperly recorded. Perhaps a record was mis-coded, such as by mis-attributing a record to the wrong state. Perhaps a record of a license or ID that has since been cancelled was left in SPEXS by a state or territory that has withdrawn from SPEXS participation.

What recourse will any of these people have? Not much, not easily, and in some cases none at all.