What’s at stake in the EU PNR debate?

This week the European Parliament is scheduled to debate (Wednesday) and vote (Thursday) on a resolution (PDF) to approve, with amendments, a proposed compromise on a directive “on the use of Passenger Name Record [PNR] data for the prevention, detection, investigation and prosecution of terrorist offences and serious crime.”

What does this mean, why does it matter, and why should this proposal be rejected?

To answer this question requires understanding (1) what PNRs are, (2) how PNRs and other travel data are already being used by European governments, (3) how this would change if the proposed EU PNR directive is approved, and (4) why and how the provisions in the proposed directive that are supposed to protect individuals’ rights would be ineffective.

(1) What are PNRs?

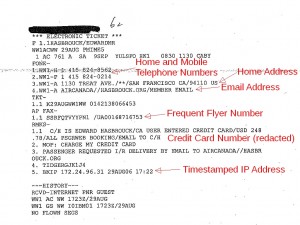

Passenger Name Records are commercial records used to store airline reservations and records related to other travel services. A single PNR can contain data about an entire family or tour group, and about all services for their trip from multiple providers: air and train travel, hotels, car hire, etc.

Perhaps the best way to conceptualize PNR data is as “metadata about the movements of our bodies.” As such, PNR data can be even more intimate than the metadata about the movement of our messages obtained through Internet or telephone surveillance, or the metadata about the movements of our money obtained from banks and other financial institutions.

PNR data reveals our associations, our activities, and our tastes and preferences. PNRs typically contain credit card numbers, telephone numbers, email addresses, and IP addresses, allowing them to be easily merged with financial and communications metadata.

Police are eager to get access to PNR data because they know how much sensitive and private information PNRs contain or can reveal.

PNRs are created by airlines, travel agencies, tour operators, and other travel companies, and are stored in databases of airlines and/or outsourced Computerized Reservation Systems (CRSs or GDSs) such as Sabre, Amadeus, Worldspan, and Galileo. The PNR data ecosystem was designed to maximize seamless, frictionless, real-time global availability of this information. The network of CRSs was the first and remains one of the largest global, real-time, outsourced, “cloud” data storage and retrieval systems, connecting tens of thousands of travel companies and storing business records about hundreds of millions of individuals.

There are insufficiently granular controls on PNR access, with no geographic or purpose limitations on access to any PNR by any CRS user, anywhere in the world. As we’ve been pointing out publicly for years, each node in the global network is a point of vulnerability to governments or criminals, for purposes that can include surveillance, industrial espionage, stalking, domestic violence, or kidnapping:

CRSs can be, and have been, hacked. It’s actually quite easy to hack a CRS and obtain PNR data without being detected. We’d be happy to discuss some of the vulnerabilities we know about with any CRS operator, airline, legislator, or data protection official who is willing to listen.

There are no records of which CRS user has retrieved a PNR, where in the world, or for what purpose. So it’s impossible to know how often PNR data is stolen or leaked, who the most common attackers are, where they are located, or how they use PNR data they have obtained surreptitiously or improperly. Airlines do not know who has retrieved PNR data about their passengers, or where in the world CRSs have transmitted this data in response to queries by CRS users.

In response to our complaints to European data protection authorities, major European airlines have admitted that even the EU-based Amadeus CRS has no access logs. Without access logs or geographic or purpose limitations on access, even an airline that relies solely on Amadeus, and doesn’t allow i’s agents to use any of the US-based CRSs, is unable to provide a complete accounting of disclosures or cross-border transfers of PNR data, as required by EU data protection law.

These deep-rooted and systemic security problems in the commercial PNR data infrastructure predate governments’ efforts to obtain root access to CRSs or to construct government mirror copies of CRS databases of PNRs. Unless the CRSs are first secured, it will be impossible to control or contain how governments use their mirror copies of PNRs.

(2) How are PNRs and other travel data already being used by European governments?

Some supporters of the proposed EU PNR directive have suggested that it is necessary in order for European police to be able to obtain or use PNR data to investigate crimes. But that’s not true. PNR data and other travel data is already extensively used by, and shared between, law enforcement agencies throughout the EU.

Police can obtain PNR data from travel companies or CRSs using search warrants, subpoenas, or other normal legal procedures, if they have a lawful basis for doing so as part of a specific criminal investigation.

If police in one country are investigating a crime involving a flight between two other countries, or a flight on an airline that stores its PNR data in a CRS based in another country, they can obtain that data from the government of the country where the data or the data controller is located, using existing international agreements for cooperation and assistance between law enforcement agencies.

Most importantly, since 2004 all airlines operating international flights to any destination in the EU have been required by Directive 2004/82/EC to transmit so-called Advance Passenger Information (API) to the government of the destination country. For each passenger, the API transmission must include:

- the number and type of travel document [e.g. passport] used,

- nationality,

- full names,

- the date of birth,

- the border crossing point of entry into the territory of the Member States,

- code of transport [e.g. two-letter airline code and flight number],

- departure and arrival time of the transportation,

- total number of passengers carried on that transport,

- the initial point of embarkation.

If the police have a lawful basis to demand additional information about an individual traveler, such as a complete copy of a PNR, the API data provides all the information they need to identify the desired PNR and demand it through existing legal procedures for access to third-party business records.

So every EU government already has all the information it needs to identify air travelers who are the subject of warrants for their arrest or detention for questioning, court orders restricting their movements, or lawful surveillance or monitoring of their travel. Given the API data that airlines are already required to send to governments, systematically transmitting PNR data about non-suspects to police does nothing to make it any easier to catch or track suspects.

Some EU members already go further, and require airlines either to “push” PNR data to the government or to allow the government to “pull” PNR data from them. The simplest way for an airline to comply with such a mandate is to tell the CRS that hosts its PNRs to give that government root access, as many airlines have done for the US government..

The UK and France — the strongest supporters of the proposed EU PNR directive — already require airlines operating flights to their countries to transmit complete copies of all PNRs to their national law enforcement and travel control agencies, in essentially the same manner as was pioneered by the USA. If other EU member states want to do likewise, they can, subject only to the constraints of their own domestic laws and of international aviation and human rights treaties. The European Commission has already been funding many of these national PNR schemes.

The proposal being debated this week in the European Parliament is not about creating or authorizing a new database. It’s about mandating the creation of more mirror copies of existing commercial PNR databases cached and held by national governments, and mandating the algorithmic profiling and mining of this cached data by every EU member state, each in its own way and according to its own profiling and scoring algorithms.

(3) How would government use of PNR data change if the proposed EU PNR directive is approved?

As the preceding discussion should make clear, the proposed EU PNR directive is not needed to “authorize” travel surveillance and control, and would do nothing to enhance the ability of the police to use airline reservations to catch suspects or track the movements of people on watchlists. Rather, the proposed directive is intended to force those EU member states that believe PNR-based surveillance, profiling, and control of travelers is ineffective or improper to do it anyway.

The proposed directive would require each EU member state to:

- Establish or designate a new travel surveillance and control agency (“Passenger Information Unit”),

- Require all airlines operating flights to or from places outside the EU to transmit complete copies of PNRs for all passengers to the government, and

- Pass on any of this PNR data to any other EU member state on request.

The proposed directive is intended to shift the government’s role in air travel, throughout the EU, from stopping suspects to “pre-crime” predictive policing. Instead of stopping people from traveling on the basis of warrants or other court orders, people would be permitted to travel only by permission of the government. The default would change from “yes” to “no”, and travel and freedom of movement would change from a right to a privilege granted by government.

That sort of permission-based travel control regime is not an attractive idea to people whose family members, friends, or neighbors had to get permission from the Nazis to leave the territory of the Third Reich, or had to get permission from the Stasi to travel outside the borders of the DDR.

The UK describes this as “an Authority to Carry (ATC) scheme in which all passengers on scheduled services would be screened before travel to the UK and denied permission to travel where appropriate,” based on “a risk assessment process, using passenger data.”

“Screening”, as this description should make clear, is a euphemism for “control”. People are “screened” to decide who to allow to travel, and who not to allow to travel.

This goes beyond mass surveillance to government control: a requirement for government pre-approval of all travel in or out of the EU. In the US, we would call a restriction like this on fundamental rights “prior restraint,” and would subject it to the highest standard of legal justification, “strict scrutiny.”

As we said in a submission cited with approval in a report last month by the UN Office Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights concerning the rights of migrants, “screening” and algorithmic travel control regimes are likely to result in systematic discrimination against asylum seekers and refugees: “Their nationality or place of origin in a conflict zone may cause them to be deemed ‘risky’ according to the profiling and ‘risk scoring’ algorithms. There may be limited, inconsistent, or nonexistent records pertaining to migrants in irregular situations in the databases used for profiling and risk scoring, and screening algorithms may equate uncertainty with risk.”

Controls on access to air travel throughout the EU on the basis of PNR profiling are thus likely to exclude many legitimate asylum seekers from travel by common carrier, forcing them to dangerous means of “irregular” and indirect transportation and compounding the EU migrant crisis. The PNR proposal is the European equivalent of Donald Trump’s proposal to build a wall on the USA-Mexico border, and would be just as disastrous.

(4) Why and how would the provisions in the proposed directive that are supposed to protect individuals’ rights be ineffective?

The proposed EU PNR directive contains several provisions that purport to insure that fundamental rights are respected. But they are window-dressing: designed to look reassuring to advocates for human rights and the rule of law, but also designed not to restrict on the practices of “pre-crime” travel policing.

The proposed directive provides that,”The competent authorities shall not take any decision that produces an adverse legal effect on a person or significantly affects a person only by reason of the automated processing of PNR data.” That sounds good, but the key word in this sentence is “solely.” As long as a human being rubber-stamps the judgment of the robot, any action that is taken will be permitted by the directive. And the profiling algorithms are likely to be so complex that the humans who exercise nominal “oversight” over their decisions will have no real alternative to rubber-stamping whatever score the computers assign.

The US no-fly list and real-time no-fly decision-making has been rightly criticized as lacking due process and evading judicial review, but it’s not clear that no-fly decision-making in the EU is any more fair, transparent, or accountable to the rule of law. Aside from the requirement for a human rubber-stamp on the decisions of computerized “black boxes”, there are no substantive standards or procedural requirements in the proposed directive for the making of no-fly decisions or the review of those decisions by the courts (if judicial review is even possible). So far as we know, no no-fly decision by any EU government or airline has yet been reviewed by any EU court.

Pursuant to the proposed directive, “The collection and use of sensitive data directly or indirectly revealing a person’s race or ethnic origin, religious or philosophical belief, political opinion, trade union membership, health or sexual life, is prohibited.” That sounds nice, but in practice it’s impossible. No law mandates that this sensitive data be entered in PNRs in any standard format that would make it possible to filter out. Business practices vary from travel agency to travel agency. Trade union membership, for example, might be indicated by a discount code for attendees of a trade union congress that is entered in the “fare basis” or “ticket designator” field on the ticket and in the PNR. To filter out such a code, the Passenger Information Unit would need an exhaustive lookup table of such codes, which is unlikely to be available. Trade union membership could also be indicated by a telephone number or address of a union office, by an email address in a union domain, or by the credit card used as a form of payment. Any or all of the categories of information specified as “sensitive” could be included in free-text remarks. Remarks can be cryptic, abbreviated in non-standard ways, and in any language used internally by the travel agency or tour operator, not necessarily an EU national language. Nobody familiar with real-world travel industry data entry practices could possibly believe that all or most sensitive data can or will be filtered out of PNRs.

(Most airline, travel agency, and tour operator staff don’t realize that anything they enter in a PNR — for example, a free-text remark to warn their colleagues about a difficult or verbally abusive or insulting customer — will be transferred to governments around the world, included in permanent government files about the person, and used as part of the basis for profiling the person and deciding how the government will treat them or whether they will be allowed to fly. Government mirror copies of PNRs include internal travel industry staff chatter and gossip never intended to be shared with the police.)

Six months after PNR data is transmitted to governments, “all data elements which could serve to identify the passenger to whom PNR data relate shall be masked out” from the copy of each PNR maintained by the Passenger Information Unit. That sounds good, but the masking is a sham: The directive omits the “record locator” — the most obviously identifying data element — from its list of “the data elements which could serve to identify the passenger to whom PNR data relate and which should be filtered and masked out”. And there is no requirement for masking of data in the master copies of PNRs held in CRSs and airline systems. The record locator is just what its name implies: a unique identifier for the PNR, designed to facilitate indexing, search, and retrieval. A PNR can be more quickly retrieved by record locator than by passenger name. If a system designer wanted to keep PNR copies anonymous, the first field they would mask out would be the record locator.

Perhaps the most serious deficiency in the proposed directive is in its analysis of impacts on fundamental rights. It should go without saying that the point of the directive is the control of individuals’ movement across EU borders. The starting point for any assessment of whether the proposal respects fundamental rights should be the criteria promulgated by the UN Human Rights Committee for evaluating whether administrative restriction on freedom of movement are permissible under international treaty law. But the proposed EU PNR directive omits any mention of the right to freedom of movement as one of the fundamental rights implicated by the proposal. This alone should be grounds to reject the proposal out of hand.

CRS are not open to public and cannot be fully accessed from the public internet. The PNR data are mostly deleted five days after booked services, Data given into PNR are mostly through web-Frontends of E-commrce travek agencies or airllnes. If travel is not booked by online bargain hunters but via a travel agency or an airlino offeíce the serious personal data is not stored within PNR, as the travek agent acepts the oaymant ad operates billing within his facilities seperate from PNR.

@Chris — You are mistaken.

(1) Yes, CRSs are not *fully* accessible from the public Internet. But each of the CRSs, and many airlines, operate Web gateways that allow substantial amounts of PNR data to be viewed without a password, as discussed at:

https://hasbrouck.org/articles/watching.html

(2) “Deleted” in CRS-speak means “moved from live storage to permanent (but still accessible) archival storage”. No airline or CRS purges data while it might be needed for credit card billing disputes. All PNR data is always retained for at least several years, and in many cases retained indefinitely. Storage is cheap. Data is potentially valuable.

(3) Both online travel agencies (using CRS APIs) *and* travel agencies that enter data manually use CRSs as their Customer Relationship Management system. CRSs encourage and provide tools within the CRS for this. Large amounts of sensitive data are entered in PNRs by travel agencies.

(4) It would be impossible to separate travel agency billing from CRSs, since it relies on ticketing and credit card charge data processed through CRSs. There are 3rd-party tools that interface with CRSs to provide additional accounting functions, but billing data has to be entered in PNRs.

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » EU mandates US-style pre-crime profiling of air travelers

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » “Following the money” in travel surveillance

Pingback: “Following the money” in travel surveillance – The Daily Coin

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » Controls on land travel vs. the right to free movement

“Travel data: fraud with booking codes is too easy” (FAQs about PNR hacking by Edward Hasbrouck, December 27, 2016):

https://hasbrouck.org/blog/archives/002279.html

Pingback: How Brexit Could Affect Media Content for Children and Families - Connected Learning Research Network

Pingback: Government access to airline PNR data challenged in German courts – Papers, Please!

Pingback: European court (again) finds US data protection inadequate – Papers, Please!