Where is the Citizens’ Commission to Investigate the DHS?

“Democracy needs whistleblowers. That’s why I broke into the FBI in 1971,” begins an op-ed by Bonnie Raines, one of the members of the previously-anonymous “Citizens’ Commission to Investigate the FBI” who took the spotlight today through public appearances and interviews and the publication of a new book about their 1971 action, The Burglary, by former Washington Post reporter Betty Medsger.

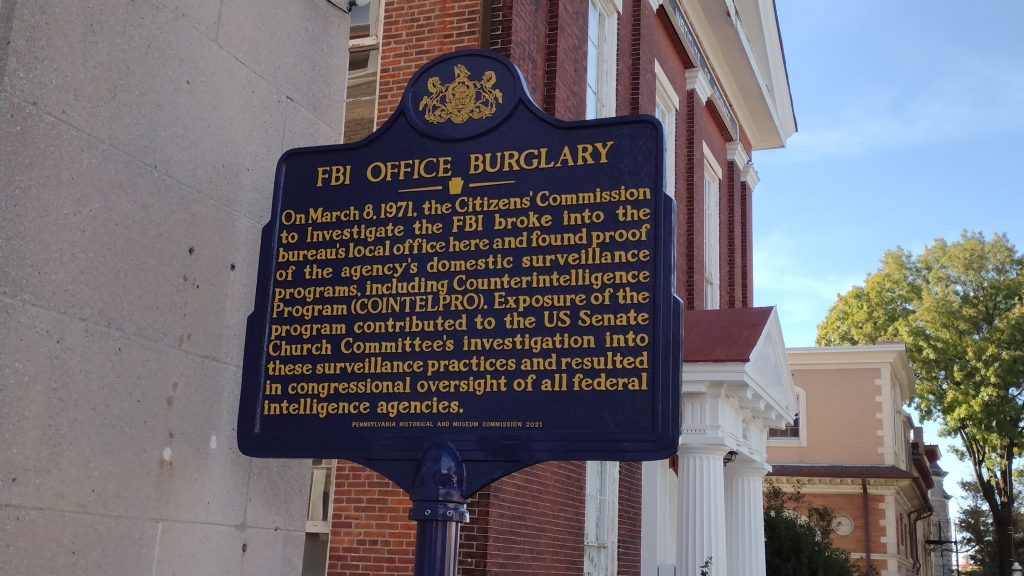

The Citizens’ Commission — Bonnie Raines, her husband John Raines, Keith Forsyth, Bob Williamson, the late William Davidon, the pseudonymous “Ron Durst” and “Sarah Smith”, and their eighth still-unnamed collaborator, referred to in the book as “Janet Fessenden” — broke into a relatively minor but also relatively poorly secured FBI office near Philadelphia, stole “probably about six big suitcases” full of documents, and sent copies of those documents revealing FBI political surveillance and “dirty tricks” to various reporters and publications.

“The Complete Collection of Political Documents Ripped-Off from the F.B.I. Office in Media, Pa., March 8, 1971” was eventually published in full a year later by the War Resisters League as a special double issue of WIN Magazine. These documents included the first public appearance of the FBI code-word “COINTELPRO“. The documents, damning the FBI and J. Edgar Hoover in their own words, and the exposure of COINTELPRO, unseated Hoover and the FBI from their “untouchable” pedestals of public respect and secret power, prompted the Church Commission hearings, and led to executive orders and legislation at least purporting to reign in FBI political surveillance and meddling in non-criminal political activities.

Daniel Ellsberg (who praises the new book, The Burglary, as “a masterpiece”) has spoken repeatedly over the years of his desire to learn the identities of the members of the Citizens’ Commission, so that he could thank them personally for their whistleblowing. Today we are finally able to give the members of the Citizens’ Commission, named and unnamed, the credit they have long deserved for their courage and commitment in service to the causes of truth and justice.

But members of the Citizens’ Commission identified themselves publicly today not to claim their rightful place in the pantheon of muckraking heroes who have taken personal risks to expose government misconduct (entitled though they are to do so) but in order to call attention to the continuing need for more actions like theirs, and to the righteousness of whistleblowers like Edward Snowden who have taken such actions more recently.

The Citizens’ Commission weren’t “leakers”. They were outsiders tapping into the sewage pipe of government secrets from the outside, not insiders “leaking” secrets from within the apparatus of government surveillance and subversion. It’s important to distinguish them from insiders like Edward Snowden, Chelsea Manning, Dan Ellsberg, and Tony Russo.

As the name of the “Citizens’ Commission to Investigate the FBI” itself quite accurately reflects, its members acted as independent investigators and investigative journalists, not “leakers”. They were the “hackers” of their time, carrying out their hacks with disguises, crowbars, and photocopiers rather than with code.

That makes the courage and commitment of the Citizens’ Commission all the more noteworthy. Ellsberg, Snowden, and Manning were all in positions of privileged access to closely-held information. The knowledge of that unusual privilege could, for people of conscience, translate itself into a greater sense of obligation to act on one’s knowledge. The members of the Citizens’ Commission, on the other hand, started out with no special knowledge and no special access. They did something that any member of the public could have done.

“But there was absolutely no one in Washington — senators, congressmen, even the president — who dared hold J. Edgar Hoover to accountability,“ John Raines told the New York Times. “It became pretty obvious to us that if we don’t do it, nobody will.”

In their press conference today, members of the Citizens’ Commission reminded reporters that the government made the same claims about the documents they stole from the FBI and gave to journalists as it has made recently about the documents taken from the NSA and passed on to journalists by Edward Snowden. In both cases, the government tried to persuade newspapers not to publish the documents, and justified criminal investigations of the thefts or leaks, on the basis of claims that the documents contained critical information that could jeopardize national security if revealed to the public.

“Within days of our action, the government was spreading stories that the documents included things like locations of missile silos and so forth,” Keith Forsyth of the Citizens’ Commission points out.

“That was a complete fabrication,” Forsyth says, based on his knowledge of documents the Citizens’ Commission eventually burned — pertaining to ordinary criminal matters rather than specifically political activities — as well as the political documents they released to the news media. Forsyth says he’ll believe Snowden has released information genuinely damaging to national security if the government produces an actual example of such a disclosure in the material Snowden has given to the press.

We should be equally skeptical of contemporary DHS claims about the “sensitivity” and need for secrecy of information about its operations. One of the lessons we draw from the FBI response to the actions of the Citizens’ Commission is that such claims are typically made primarily to protect government officials against public accountability, not to protect the public against private crime or threats from abroad.

The Citizens’ Commission initially sent portions of the FBI documents to members of Congress — who said nothing publicly but immediately turned the documents over to the FBI to aid in its investigation — and to selected reporters at the Washington Post (Medsger), the New York Times (Tom Wicker), and the Los Angeles Times (Jack Nelson).

“The New York Times gave the documents immediately to the FBI, that day,” Medsger says, and initially acceded to requests from the government not to report on any of the contents of the documents. Only after the Washington Post had published articles based on the documents did the New York Times begin to do likewise. Neither the Post nor the Times ever published the FBI documents they received from the Citizens’ Commission in full, the way both the Post and the Times would later do with the Pentagon Papers. That was left to WRL and WIN Magazine, part of an activist alternative press that played a role, as secondary heroes of the events, comparable to that of Wikileaks today in publishing documents leaked by Chelsea Manning and others — but in a time when publishing and information dissemination, particularly in volume, was much more expensive than it has become in the Internet era.

In response to our question about this during today’s news conference, Medsger was relatively forgiving of the mainstream newspapers’ decisions at the time. “This was the first time that news outlets had received stolen government documents like this,” she says. “It was the first time that Katherine Graham [owner and publisher of the Post] had been faced with a demand from the government not to publish.”

Back when mainstream newspapers and alternative publications like WIN Magazine received the “Political Documents Ripped-Off from the F.B.I. Office in Media, Pa,” with J. Edgar Hoover still in power, nobody knew what the consequences might be of writing about the contents of these documents, much less of publishing them verbatim.

This was before the Pentagon Papers cases, in which President Nixon decided not to have the Department of Justice pursue criminal charges against the New York Times or its reporters.

Tony Russo and Dan Ellsberg were prosecuted (although the charges were dismissed by the trial judge due to misconduct by the government) for theft of government property and for violating their secrecy oaths as employees of a military contractor and holders of security clearances. But none of the newspapers, reporters, editors, or publishers who received and reprinted copies of the Pentagon Papers were prosecuted, even though they knew that the documents were classified and had been “leaked” illegally. Regardless of how their sources had obtained the Pentagon Papers, the newspapers and journalists who published the documents hadn’t agreed to security clearances, and hadn’t engaged in theft or violated secrecy oaths or employment agreements.

We’ve published documents the TSA tried to hide from the public when the DHS itself has inadvertently made such documents public, regardless of whether they are marked as “sensitive security information”. The DHS has harassed journalists involved in reporting on and reprinting these documents, but hasn’t prosecuted us or anyone else for publishing these documents. We believe that our actions have been within the law and protected by the First Amendment.

Our actions in publishing these documents have been intended to expose unlawful activity, bring government employees and agencies into compliance with the law, and defend the national security against the foreign and domestic enemies of our Constitutional liberties and human rights.

Why wasn’t the FBI able to identify the Media burglars, despite J. Edgar Hoover’s ire and the Bureau’s best (or worst) efforts? Safety in solidarity and numbers, essentially: “People who are not of our generation have trouble imagining what it was like at that time. There were tens of thousands, or at least thousands, of very [politically] active people in Philadelphia,” Forsyth noted today. “There were an awful lot of potential suspects, and none of those people thought of the FBI as their friend.” [Large portions of the FBI’s “MEDBURG” file on its unsuccessful investigation of the Media burglary, released decades later in response to requests under the Freedom of Information Act, are available online here.]

How different is the situation today with respect to the NSA or the DHS? “Homeland Security” has its supporters, as did J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI in their illegal defense of what they thought of as “the American way of life” (not including, needless to say, the Bill of Rights) against the alleged “Red Menace” of the New Left and the antiwar and civil rights movements. But as the visible, hands-on “pointy end” of DHS attacks on our rights, the TSA is among the most widely-disliked and least credible components of the entire Federal government. Why aren’t there more citizen investigations of TSA and DHS misdeeds?

And why have there been leaks from within the military (Manning) and the NSA and its contractors (Snowden), but so far as we can tell, nothing remotely comparable from within the DHS or its contractors?

We wouldn’t want to have to decide which agency is worse, the DHS or the NSA. The NSA doesn’t appear to have much, if any, edge on the DHS for overt lawlessness. The DHS has argued explicitly and publicly that its decisions should be exempt from judicial review, and that it has limitless “discretion” to collect secret dossiers about us and our movements and to use those secret files, again at its “discretion”, in making secret, standardless, unreviewable decisions as to whether to “permit” us to exercise our right to travel and to be free from unreasonable extrajudicial search and seizure.

These are the sorts of outrages of which the Citizens’ Commission only suspected the FBI.

We hope that knowledge of the actions of the Citizens’ Commission, who they were, and what they did, inspires others to reveal the details of today’s illegal government programs, including those of the DHS.

Longer interviews with members of the Citizens’ Commission to Investigate the FBI:

Part 1:

http://www.democracynow.org/2014/1/8/it_was_time_to_do_more

Part 2:

http://www.democracynow.org/blog/2014/1/8/from_cointelpro_to_snowden_the_fbi

Pingback: Federal Air Marshals blow the whistle on TSA “Quiet Skies” traveler surveillance program | Papers, Please!

Pingback: How the Chicago 7 might have been the Chicago 9 | IPRA Peace Search