Airline and TSA insecurity

Recent news stories have called new attention to longstanding vulnerabilities in the security of travelers’ luggage and personal information created by TSA and airline practices.

Exhibit A: TSA-mandated “key escrow” for luggage locks:

Before the creation of the TSA, airline passengers were encouraged by airlines to secure their suitcases with locks against pilferage in transit. Some airlines’ rules provided that unless passengers locked their luggage, they would not be reimbursed for items that went missing from their luggage.

The TSA, in its infinite wisdom, initially decided that everyone would be more secure if travelers were forbidden to lock our luggage, so as to make it as easy as possible for anyone (especially, of course, TSA staff and baggage handlers) to introduce dangerous items into luggage, or remove valuables from luggage.

The predictable result was a wave of organized theft from checked luggage by groups of TSA staff and baggage handlers at airports throughout the country who used “security” x-rays of luggage to identify which bags contained things worth stealing. 400 TSA employees have been fired for stealing from luggage since 2003. As for airline and airport staff, 37 have been arrested in multiple cases of organized luggage theft at the Miami airport alone just since 2012.

In response, the TSA proposed a fig leaf of pseudo-security: Starting in 2003, air travelers were once again allowed to lock our bags — but only with TSA-approved “Travel Sentry” locks which could all be opened with one of a small set of master keys provided to all TSA baggage screeners.

That makes no sense, of course, in terms of any rational threat model: Almost the only people who have access to checked luggage in transit are airline, airport, and TSA staff. Unsurprisingly, allowing the use of locks to which all of the likely thieves were given master keys did little or nothing to deter or decrease theft.

But that’s not all. Any “key escrow” system is only as secure as the controls on access to the master keys or the information needed to replicate them. The other shoe has now dropped: Specifications for the TSA master keys (obtained from photos accurate enough to make working keys) have been made public. Anyone with a 3D printer can use these files to make their own complete set of keys to open any Travel Sentry lock.

For what it’s worth, while you aren’t allowed to use physical measures to secure your luggage, you still have some legal protection, at least in theory. Up to a liability limit fixed by law, the airline is strictly liable for loss, theft, or damage to luggage or contents between the time the passenger is given a claim check and the time the passenger reclaims their luggage. The TSA and the airlines both want to divert passengers into an arduous claims process against the TSA, but it’s actually the airline that is liable to the passenger for any damage to luggage while it is checked, even if the damage is caused by the TSA or any other third party. You can sue the airline in small claims court for any damage between check-in and baggage claim. The airline can pursue a claim against the TSA, but that’s not your problem and has no affect on the liability of the airline to the passenger. If airlines have to absorb some of these losses, maybe they’ll get motivated to rein in TSA thievery.

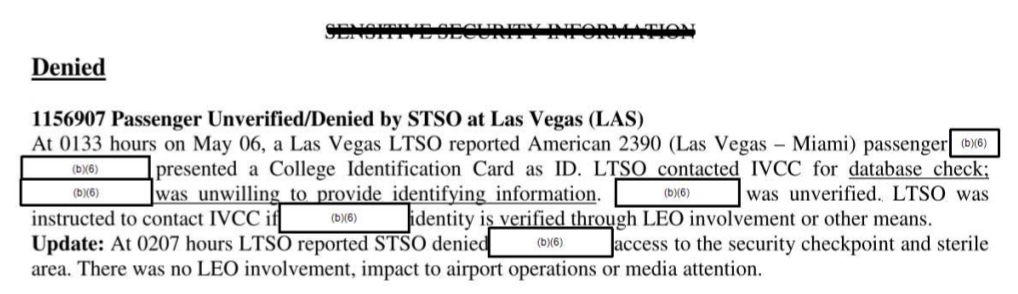

Exhibit B: Airlines’ use of non-secrets printed on boarding pass stubs and checked-baggage tags as “passwords” for access to the details of airline reservations and personal profiles:

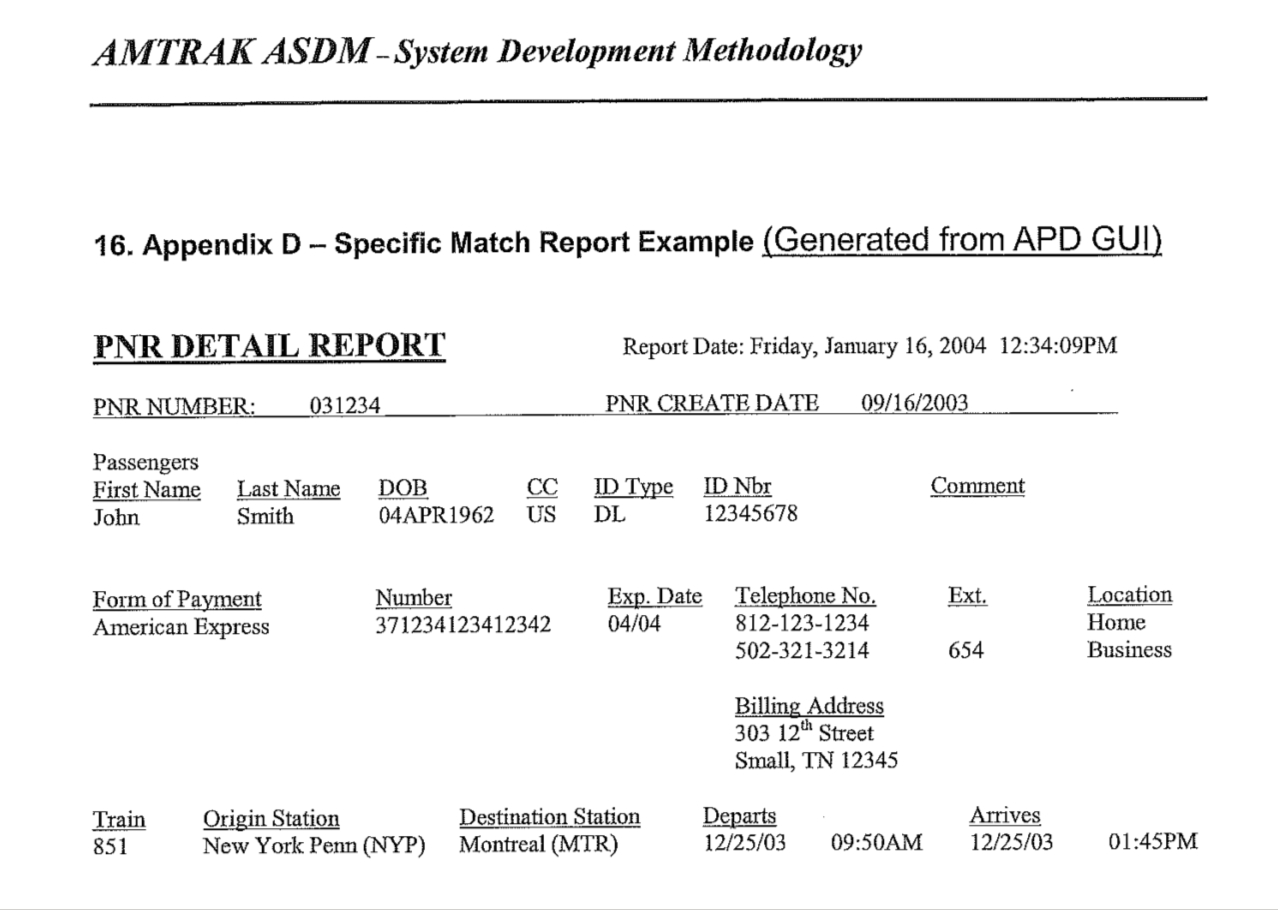

Airlines store “passenger name records” (PNRs) in “computerized reservation systems” (CRSs) that were developed for purely internal use by airline and travel agency staff. Access to reservations and passenger profiles was controlled by physical controls on access to networked terminals, and by user IDs and passwords for system access. Once a CRS user was logged in, they could retrieve any PNR by “record locator”. There’s never been an individual password in the CRS for each PNR or each passenger profile.

Record locators and passenger names were and are printed on boarding passes, baggage tags and claim checks, and itineraries. At first they were machine-printed in text. More recently they have also been incorporated into barcodes with standard and publicly-disclosed encoding.

Nothing changed when CRSs were connected to Web gateways for self-service booking, ticketing, itinerary review, check-in, and so forth. Once a user is “signed in” to a CRS, all they need is a record locator and name to retrieve all or part of the data in a PNR of interest. But now every Web user in the world is, in effect, already signed in to the CRSs through these Web gateways provided by airlines and directly by each major CRS. Not all of these sites display the same subset of data, but even the most basic information available at any itinerary-viewing or check-in site (Where is this passenger going? When are they coming back?) can pose a major threat in the hands of house-burglars, stalkers, domestic abusers, or kidnappers.

Airlines and CRSs have been alerted and aware for years of the vulnerability created by the lack of passwords for access to PNR data, but have chosen to do nothing. Do they think it wouldn’t be worth the cost? Or do they think that if travelers had to remember and use a password to check in online, they would check in at the airport instead, taking up more airline staff time? Your guess is as good as ours.

The latest report this week from IT security expert Brian Krebs is that some airlines have expanded the information accessible with only the data on a discarded boarding pass (or, we suspect, a baggage tag) from the PNR for a single journey to the passenger’s entire travel history and profile from their frequent flyer record. Krebs found that he could even hijack the password on a frequent flyer account using the information encoded using a public algorithm on a boarding pass barcode. That, in turn, would allow ID thieves to have “free” tickets issued for themselves or other criminals, using the target’s mileage points.

What’s the takeaway? Neither the TSA nor the airlines have paid the least attention to rational risk assessment, risk-based security, or even the most elementary norms of physical and data security. Yet these are the entities to which the government wants to compel us to turn over even more personal information.