Congress asks more questions about TSA blacklists

The “No-Fly” and “Selectee” lists managed by Federal agencies through the joint Watch List Advisory Council (WLAC) aren’t the only blacklists and watchlists that are used to determine who is given US government permission to board an airline flight, and how they are treated when they fly.

Senior members of relevant House and Senate Committees are asking overdue questions about the blacklists created and used by the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) to target selected travelers for special scrutiny, surveillance, and searches when they fly.

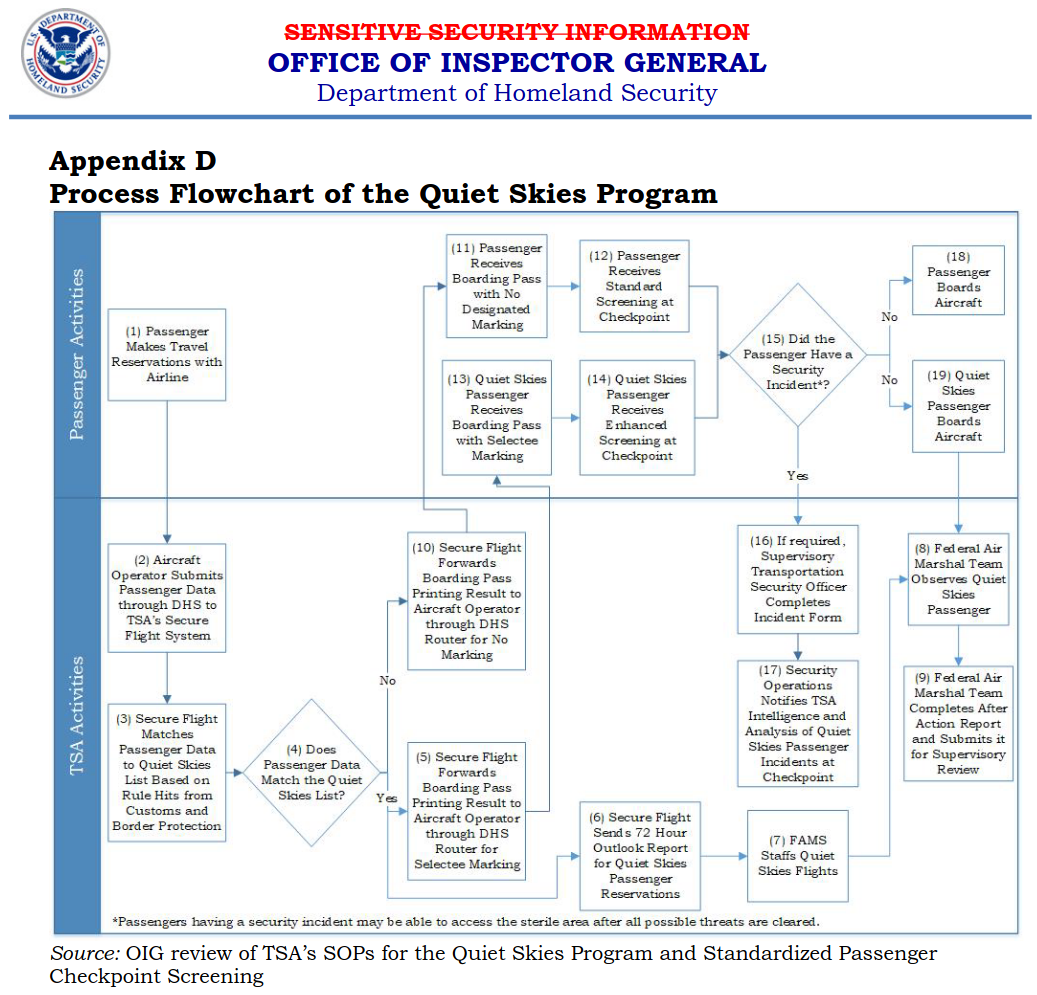

The TSA’s Secure Flight program is used to determine, on the basis of identifying and itinerary information from ID documents and airline reservations, what Boarding Pass Printing Result (BPPR) to send to the airline for each would-be passenger. The ruleset included in the Secure Flight algorithm includes list-based and profile-based Quiet Skies rules created by the TSA itself, independent of the interagency No-Fly and Selectee travel blacklists.

These Quiet Skies rules are used to flag certain airline passengers as “Selectees” to be searched more intrusively at TSA checkpoints (even if they aren’t on the interagency Selectee list), and to assign Federal Air Marshals (FAMs) to follow, watch, and file reports on their activities in airports and on flights. A secret alert is sent to FAMs, based on airline reservations, 72 hours before each planned flight by a person on the Quiet Skies list.

The Quiet Skies program was implemented secretly in 2012. “In March 2018,” according to a later report on the Quiet Skies program by the DHS Office of Inspector General (OIG), “in addition to enhanced checkpoint screening, TSA began surveillance (observation and collection of data) of Quiet Skies passengers beyond security checkpoints, as part of its Federal Air Marshal Service’s (FAMS) Special Mission Coverage flights.

The No-Fly list and profile-based no-fly rules are used in the Secure Flight travel control and surveillance algorithm to determine who is allowed to fly. The Selectee and Quiet Skies lists and rules are used to determine who to search and surveil when they fly.

The Quiet Skies program came to light later in 2018 when FAM whistleblowers went to the Boston Globe with their complaints that the wrong travelers were being targeted, mis-prioritizing which flights FAMs were being assigned to. These FAM whistleblowers complained, that, for example, anyone identitied from airline reservations as having traveled to Turkey was put on the Quiet Skies list and had a FAM assigned to each US flight they took for the next several months, including domestic flights. Travelers’ reports of being followed through airports (presumably by FAMs) and subjected to more intusive searches at TSA checkpoints after trips to Turkey supported these allegations.

The TSA initially declined to confirm the existence of the Quiet Skies program. But in response to questions from Congress and follow-up reprting by the Globe, the TSA released a belated Privacy Impact Assessement (PIA) for Quiet Skies in 2019. However, that PIA specified none of the Quiet Skies rules and gave no demographic or other information about who those rules had targeted.

Additional descriptions of the program, including the flowchart above, but still not including any of the Quiet Skies rules, were included in a critical DHS OIG report on the program in 2020.

Since January 6, 2021, there has been a new round of complaints by travelers and disgruntled FAMs that participants in the activities that day at the US Capital have been put on the No-Fly, Selectee, and/or Quiet Skies lists.

This month a redacted version was made public of a formal complaint to the DHS OIG by a FAM who says his wife was put on the Quiet Skies list and “targeted for FAMS ‘Special Mission Coverage’ simply because she attended President Trump’s January 6, 2021 speech at the ellipse in Washington, D.C.” FAMs also said that former US Representative and Presidential candidate Tulsi Gabbard has been put on the Quiet Skies list because of her role in the January 6, 2021 events. When she read those reports, Gabbard said that, “The whistleblowers’ account matches my experience” of disprate treatment at TSA checkpoints.

We’ve been unable to confirm or disprove these reports. But we find them plausible and — whether or not they are true — indicative of fundamental problems in these arbitrary, secret, extrajudicial schemes for making decisions about the exercise of our right to travel by common carrier and to be free from unreasonable searches and seizures.

There have been repeated, although in our opinion misguided, calls to put anyone who participated in the storming of the US Capital on the existing No-Fly list, as well as to give the TSA the legal authority to create its own addtional no-fly lists and profiling rules. Given the TSA’s track record of imposing new restrictions on travel first, and disclosing them or asking for approval later, if at all, we can certainly imagine that the TSA might already have put some January 6th suspects on its watchlists, sua sponte.

Regardless of the merits of these sanctions in these circumstances, this is unnecessary and wrong. No new law and no exception to due process is needed to impose these sanctions.

Law enforcement officers with probable cause to suspect crimes — whether at the US Capital on January 6, 2021, or at any other time and place — can apply for search warrants.

Prosecutors can also request, and judges can and routinely impose, restrictions on travel as a conditions of release pending trial or as a condition of probation or parole for those duly charged or convicted of crimes. Similar restrictions can be imposed on others not charged with crimes, if they are justified to judges through existing adversarial, evidence-based, judicial procedures for the issuance of injunctions or restraining orders.

Secret, extrajudicial blacklists are an invitation to political and other abuse. January 6th suspects are entitled to their day in court, including notice of the charges against them; an opportunity to confront, cross-examine, and rebut witnesses and evidence; and decisions made and explained on the record by judges and subject to appellate review.

Interest in Quiet Skies had largely faded since the first revelations in 2018. But the latest allegations have gotten the attention of some influential members of Congress.

On August 21st, Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY), Ranking Minority Member of the Senate Committee on Homeland Security, wrote to the Administrator of the TSA requesting a wide range of recrods of TSA policies, procedures, and actions related to the Quiet Skies program.

Two days later, Rep. James Comer (R-KY), Chair of the House Committee on Oversight and Accountability, wrote to the Administrator of the TSA requesting TSA records specifically related to the latest complaints from FAMs and Ms. Gabbard, but also including “All documents and communications regarding the implementation of the Quiet Skies program” and asking the TSA to brief the Committee’s staff about the use of Quiet Skies.

The request from Sen. Paul is especially interesting. It includes the criteria that trigger inclusion on any of the TSA’s travel blacklists and watchlists, an accounting of the number of individuals on each of these lists in each month since January 2021, and a breakdown of the reasons for their inclusion on those lists. Much of this information has never been made public and may not have previously been provided to Congress.

Any response from the TSA will be provided only to Congress, and what if any portion of it to make public will be up to the members of Congress and Committees that receive it.

Concern about political weaponization of travel blacklists and watchlists, including their potential use against those who were at the US Capital on January 6th, was part of the impetus for the introduction of the Freedom to Travel Act of 2021. That bill expired without a hearing at the end of the 2021-2022 Congressional session, but could be reintroduced as a standalone bill or included in a larger legislative package. As we noted when it was introduced, the Freedom to Travel Act would be the most significant reform in the legal framework for the operation of the TSA since that agency was created in 2001.

Sen. Paul and Rep. Comer are asking good questions, but members of Congress can and should do more than ask questions. Congress should enact legislation to rein in the TSA and to make its actions against individual travelers accountable to the rule of law.

Pingback: 国会询问有关TSA黑名单的更多问题 - 偏执的码农

Pingback: Final Edition: Claim Your Free Piece of Aviation History with United’s Last Hemispheres Magazine! [Roundup] - View from the Wing

Very good, though how well federal agencies will follow any law is another question. The existence of any “no fly” list is an admission by the TSA that it can’t trust its own screening procedures–after all, if it did then it wouldn’t matter who was on board. But in any case, what we now appear to have are multiple and overlapping lists in both the private and public sector with literally millions of names, a recipe for mass confusion and misidentification. And adding people out of spite is certainly a distinct possibility. I once wrote an article on “Mafia” families in the NYC area in the 1940s and ’50s, using in part an FBI list of known members. Comparing that with books on the topic I found many, many erors of names, duplications, the inclusion of dead people, etc. I doubt computers have made this sort of thing any better. Unless proven otherwise, citizens traveling in our own country should be a right, not a toy to be put away because someone else feels like it.

Pingback: Inside the Biden Administration’s “Quiet Skies” Program: Political Targeting, VIP Exemptions, and $200M in Costs – tv503 New York News