There’s been an argument on Twitter about whether we should have described the treatment of Dr. Rahinah Ibrahim — the plaintiff in the first lawsuit challenging a US government no-fly order to make it to trial — as “Orwellian” or “Kafkaesque”. We’re inclined to agree with those who say, “But it’s both.”

True to form, day three of the trial began with arguments over whether the court could take judicial notice of statements made by the defendant government agencies on their own “.gov” websites, and of news articles linked to from the government’s own press releases on those websites.

“I would expect that the defendants would not dispute the statements that are made on their own websites,” said Christine Peek, one of Dr. Ibrahim’s attorneys. Eventually the government’s lawyers agreed to allow their clients’ press releases, and the articles from other sources they had cited and linked to, to be entered into evidence — but not without first putting up a fight about their admissibility.

While the first two days of the trial focused on what had happened to Dr. Ibrahim (she was denied boarding for a flight from San Francisco to Hawaii, falsely arrested and mistreated at the airport, and subsequently had her U.S. visa revoked), today’s testimony focused on why and how the U.S. government decided to take these actions against Dr. Ibrahim.

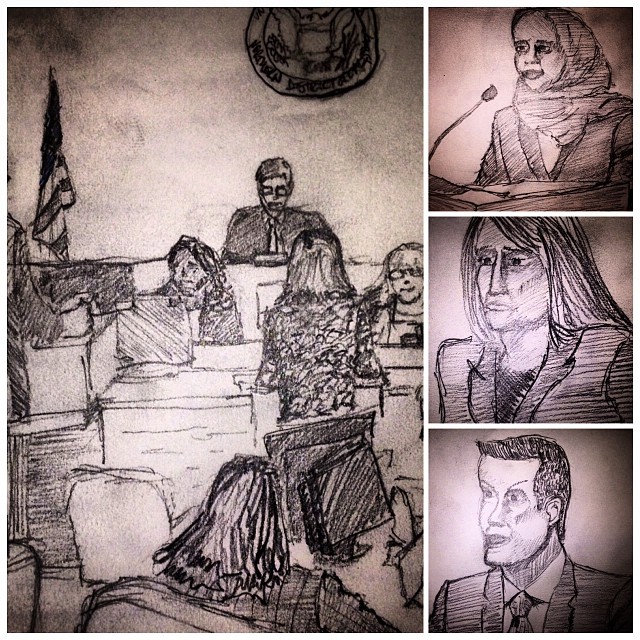

Testimony was presented in a variety of formats. Some witnesses appeared in person, others through excerpts from video recordings of depositions, and others through a surreal sort of stage play in which lawyers for the parties enacted portions of the depositions, using the transcripts as their script.

Perhaps the strangest moment came during one of these re-enactments for the record of Dr. Ibrahim’s deposition. The government’s lead counsel took the witness box to read Dr. Ibrahim’s lines from the transcript, while Dr. Ibrahim’s lead counsel played the role of the government’s lawyer cross-examining her client.

Dr. Ibrahim, of course, was the one witness who had no option of testifying in person at her own trial. The State Department’s witness today confirmed that Dr. Ibrahim applied for a U.S. visa in 2009 for the specific purpose of coming to San Francisco to be deposed in this case. Knowing that was the purpose for her trip, the State Department denied her application for a visa.

The government’s attorneys objected to questioning about why that visa application was denied, and most of those objections were sustained on the grounds that the reasons for the visa denial, like those for the “nomination” and placement of Dr. Ibrahim on the no-fly list by the FBI and its Terrorist Screening Center, were “state secrets.”

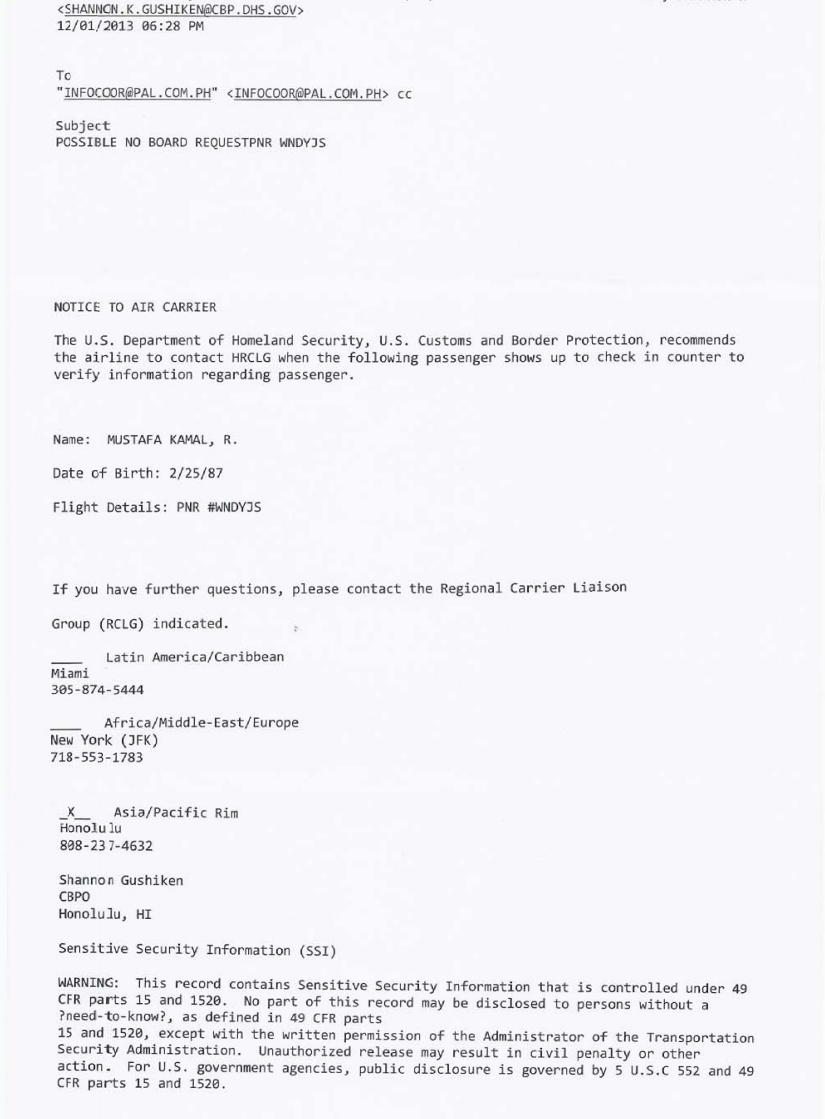

However, the limited State Department testimony that was allowed to be presented in open court suggested that the State Department visa officers who denied Dr. Ibrahim’s application in 2009 did so purely on the basis of the fact that her name had been placed on a so-called “watchlist” in 2004 or 2005, without any review or even knowledge of the “derogatory” information (if there ever was any) which had been alleged by the original “nominating” FBI agent to provide a basis for that watchlist placement. [The term used throughout the trial was, “watchlist”. But these lists aren’t used solely as a “watching” or surveillance tool. They are also used as the basis for “no-board” orders to airlines, and other actions. We think “blocking lists” or “blacklists” would be more accurate labels for these lists.]

Most of the testimony from government witnesses (the former acting deputy director of the Terrorist Screening Center, the FBI agent who personally “nominated” Dr. Ibrahim for inclusion on the no-fly list, and the State Department’s designated official representative for the officer who revoked Dr. Ibrahim’s visa) was presented in a closed courtroom from which the press and the public were excluded because the testimony included what the government claimed was “Sensitive Security Information.”

“I have to ask you to leave the courtroom for reasons that don’t make much sense sometimes. I’m sorry for that,” Judge William Alsup said when the government insisted that the court be cleared.

In contrast, the plaintiff’s first expert witness, Jeffrey Kahn, was allowed to testify in open court — over the government’s objections — because all of his testimony was based on publicly-available information and interviews he conducted as part of his research as a law professor and author. The government’s lawyers repeatedly interrupted Professor Kahn’s testimony to demand that he identify the public-domain sources for his statements, even though he had already done so in his written pre-trial expert report and in the footnotes to the scholarly book and law journal article on which most of his report and testimony was based.

At one point, in response to such an objection, Prof. Kahn identified the source for one of his statements as being FBI watchlist guidelines released by the FBI itself to the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC), and posted on the EPIC website. Those documents showed that the mere opening of an investigation was itself deemed to be presumptively sufficient grounds for placing a person on a watchlist, without the need to evaluate whether there had been any factual predicate for the opening of the investigation. This contradicted the government’s claims about the existence of threshold evidentiary criteria for watchlist decisions.

The government’s lawyers tried to argue that despite having been released by the FBI itself in response to a FOIA request, and having been publicly available for years on the EPIC website, these documents couldn’t be discussed publicly.

Judge Alsup overruled their objection. “This is America. You can’t take something that is in the public domain and make it a secret. If you wanted to shut down that website, you should have done so. It’s too late now.”

The essence of Prof. Kahn’s testimony was the absence from the watchlist procedures of essential elements of due process: notice, opportunity to be heard, and the ability to have decisions reviewed by an entity independent of the decision-making agency. As Prof. Kahn summarizes this in his book, on the basis of information including interviews with the officials who established and operated the system of watchlists:

The watchlisters are prosecutor, judge, jury, and jailer. Their decisions are made in secret and their rules for decision — like their evidence for deciding — are classified. There is no appeal from the decisions of the watchlisters, except to the watchlisters themselves.

This is key to Dr. Ibrahim’s complaint, which is both (1) that there was no, or no sufficient, factual basis for her placement on the no-fly list and other watchlists, and (2) that the decisions to place her on those watchlists violated due process, regardless of any evidence on which they might have been based, because she was not given notice, an opportunity to rebut any allegations against her, and an opportunity to have the decisions independently reviewed.

As an expert witness relying on public sources, Prof. Kahn couldn’t testify about any of the specific facts of Dr. Ibrahim’s case. But his testimony could establish facts about the decision-making process (which the government says is itself a “secret” even when it is public knowledge) sufficient to show that it lacks essential elements of due process.

Prof. Kahn testified that his interviews and research led him to the conclusion that the real decisions about entries on watchlists are made by the Terrorist Screening Center. The TSC was established in 2003 by a purely executive act, Homeland Security Presidential Directive 6. The Terrorist Screening Database (TSDB), which includes the “no-fly” list, is maintained by the TSC.

What’s the standard for inclusion of an individual on the TSDB? “It’s one level above a hunch,” Prof. Kahn testified. “It’s the lowest level known to the law, a so-called reasonable articulable suspicion.” Not proof beyond reasonable doubt, not a preponderance of the evidence, not probable cause.

There is no statutory basis for the actions or authority of the TSC. There have never been any publicly promulgated regulations or notice and comment regarding the actions of the TSC. There are “criteria” for TSC actions, but there are exceptions to those criteria . According to Prof. Kahn, “The TSDB is not limited in its use by any logic, or by any statute. It’s limited only by the imagination of those who created it.”

Is there any external review of the process? “No, no,” Prof. Kahn testified. “If an individual is nominated for the TSDB, there’s no one you can appeal to, and the individual probably won’t even know. Certainly there’s no notice to the individual. There’s no way for an individual to contact the TSC,” and its location is officially “secret” although it has been publicly revealed.

The only way to “appeal” a TSC decision or TSDB placement, Prof. Kahn continued, is the DHS TRIP program. That’s an appeal to the same agency that may have made the decision. “You can fill out the form on the TRIP website, push send, and it goes into a black box. At some later time you might get a letter in the most Orwellian terms” from which you can’t tell what action, if any, has been taken, or if so, by whom. “The only way to tell if you have been taken off the no-fly list is to try to fly again,” and see what happens.

Most of the facts and opinions in Prof. Kahn’s testimony today and the written expert report he submitted to the court in this case are developed in much greater detail in his recent book, Mrs. Shipley’s Ghost: The Right to Travel and Terrorist Watchlists. While his testimony and expert report were confined to a narrower set of issues, it’s worth considering the larger thesis within which he places them in his book:

All travelers now require the federal government’s express prior permission to board any aircraft (or maritime vessel) that will enter, leave, or travel within the United States. Of course, no one realizes that permission is required — or has even been sought — until it has been refused….

Although the government permits the airline to sell [a] ticket right away, that reservation cannot be redeemed for a boarding pass without the government’s assent… In other words, each time you travel by airplane in American airspace, it is by the grace of the U.S. Government…. [E]very time a citizen wishes to fly somewhere, the state must approve the itinerary….

I reject the premise that puts a citizen’s right to travel into conflict with national security. The premise is that the state has a right to restrict any citizen’s travel that frustrates the state’s foreign policy or national security objectives. This premise naturally suggests a balancing test: when national security outweighs a citizen’s interest in travel (and, so characterized, it nearly always can be made to seem to do so), the state should prohibit this travel. But… [c]itizens of a republic… should be no more obliged to abridge their travel to serve the state’s interests than they are obliged to curtail their speech when it conflicts with the state’s preferences…. It is rarely constitutionally appropriate to weigh a citizen’s travel interest against how that itinerary will affect foreign policy. Travel restriction in the service of the state is the hallmark of authoritarian regimes, not democratic republics….

The right to travel should be curtailed only to the extent that strict judicial scrutiny determines it is necessary to achieve a compelling government interest. A secret, summary, executive decision to curtail all air travel for an indeterminate time and without meaningful procedures to contest the decision would not pass such review. The No Fly List must be adapted to our liberty rich society, not the other way around.

These are, of course, the arguments that we’ve been making for many years, and we’ve been the only organization to testify and file formal objections on these grounds at each stage of the implementation of this permission-based travel control regime. We hope Dr. Kahn’s research and writing draws more attention to the unconstitutionality of this system, and the need to base travel restrictions on judicial orders.

The plaintiff’s lawyers plan to present their final witnesses on Thursday, after which the defendants are expected to move (again) for exclusion of most of the evidence and dismissal of the complaint on the grounds that the remaining evidence is insufficient to satisfy the plaintiff’s burden of proof. Unless that motion is immediately granted, the defendants will present their case on Thursday and Friday.