At yesterday’s first meeting of a new Minnesota “Legislative Working Group on REAL-ID Compliance“, state lawmakers’ concerns centered on (1) whether residents showing state-issued IDs will be prevented from boarding domestic flights, or harassed and delayed by the TSA, if the state doesn’t agree to “comply” with the REAL-Act Act to the satisfaction of the DHS, and (2) what compliance with the REAL-ID Act would mean for the state’s database of information about people with Minnesota drivers’ licenses or state ID cards.

The DHS has been trying to mislead state officials and the public about both these issues. Understanding both, and separating fact from DHS fiction and innuendo, is key to understanding the REAL-ID Act.

A report from a legislative analyst with the legislature’s research department distributed at yesterday’s meeting asserts that, “At some unspecified point in time (which could be in 2016), a REAL ID-compliant form of documentation will become required to fly in scheduled airline service.” But — oddly for a purported legislative analysis or research report — no authority is cited for this alleged legal “requirement”.

In fact, as we testified yesterday and as we have confirmed through more than a decade of litigation, research, and FOIA requests, this key claim — the threat being used by the DHS to induce reluctant states to accede to DHS requests for “compliance” — has no basis in any publicly-disclosed law or regulation.

People fly without ID every day, and the TSA has procedures for that, as we’ve heard them testify in court. People without ID may be (unlawfully) harassed and delayed at TSA checkpoints and airline check-in counters, but the TSA’s responses to our FOIA requests for its daily reports on how many people try to fly without ID show that almost all of these people are allowed to fly. And those few people who are prevented by the TSA from traveling by air, like the larger numbers who are harassed or delayed by the TSA merely because they don’t show ID or answer other questions, likely have cause for legal action against the TSA. They deserve the support of the states where they reside.

If you lose your wallet and find out the next day that your mother is dying 2,000 miles away, as happened to a friend of ours in St. Paul just before Christmas, you don’t have time to get your driver’s license replaced or take a bus across the country. You need to get on a plane right away, without ID. That’s what our friend did, and fortunately she got there in time. The TSA isn’t going to try to stop you from seeing your mother before she dies. That’s not a case the TSA wants to take to court, or would be likely to win.

But what’s this other question about the database?

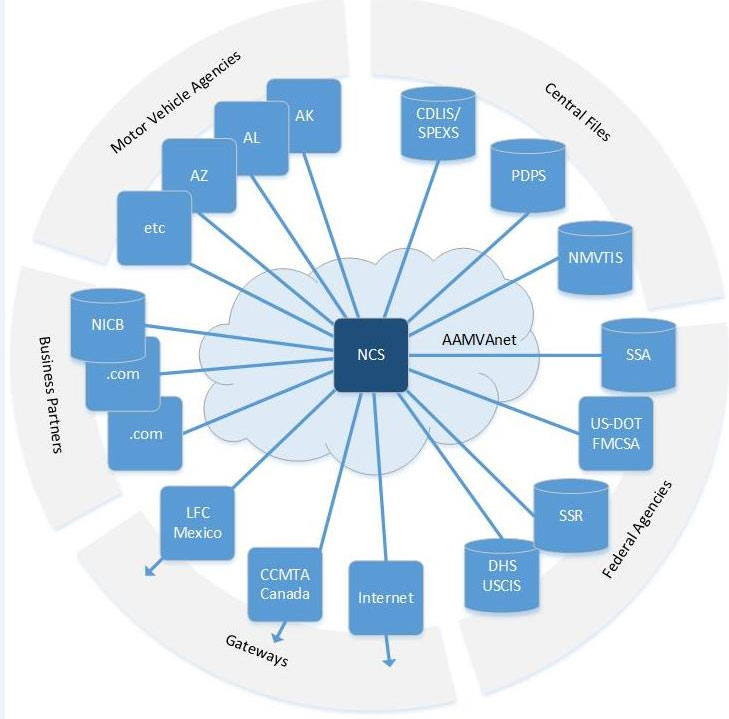

To meet the requirements of the REAL-ID-Act, a state must “Provide electronic access to all other States to information contained in the motor vehicle database of the State,” including, “all data fields printed on drivers’ licenses and identification cards issued by the State.” In effect, this would allow state databases to function as part of a distributed but national ID database system.

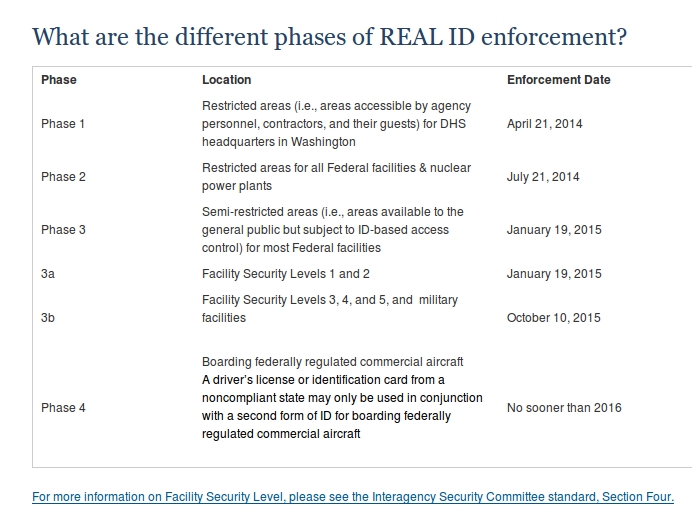

The DHS has picked out only a subset of the statutory requirements in the REAL-ID Act to consider in deciding whether to exercise its statutorily standardless discretion to certify whether states are making progress toward compliance or to grant them discretionary waivers of “deadlines” which have been set by the DHS in its discretion, and can be and have been repeatedly postponed in the exercise of that same discretion.

The initial DHS-selected criteria don’t include the requirement in the law for nationwide access by state agencies to other states’ drivers’ license and ID databases. DHS undoubtedly knows that this is one of the most objectionable, and potentially one of the most difficult and costly to implement, of the elements of state “compliance” with the REAL-ID Act, and has tried to downplay or deny the plain language in the law requiring unrestricted interstate access to drivers’ license databases. Including full interstate database access in its “compliance” criteria also would probably compel DHS, if it was to be honest, to concede that no state has yet fully complied with the REAL-ID Act.

But state officials shouldn’t be fooled: A state that agrees to “comply” with the REAL-ID Act is agreeing to comply with all of its provisions, including the database access mandate, not just the less objectionable portions that the DHS has decided to focus on first.

Once a state agrees to comply, it no longer has any leverage to move Congress to change those requirements. The only power a state has to exert pressure for change in the REAL-ID Act requirements, or their repeal, is to withhold state agreement to comply until those requirements are amended to its satisfaction, repealed, or overturned by the courts as unconstitutional.

Read More →

[The REAL-ID “hub” connects state and Federal agencies, private commercial third parties, and centralized, national database files. AAMVA SPEXS Master Specification (AMIE), r6.0.8, page 5]

[The REAL-ID “hub” connects state and Federal agencies, private commercial third parties, and centralized, national database files. AAMVA SPEXS Master Specification (AMIE), r6.0.8, page 5]