A federal judge is hearing arguments today on whether the state of Texas has complied with the District Court’s earlier rulings and a decision of the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals that portions of the Texas state law requiring specific government-issued ID credentials as a prerequisite to voting are unconstitutional.

Today’s US District Court hearing in Corpus Christi is only the latest skirmish in a nationwide legal war between advocates for ID requirements and advocates for voting rights.

Even judges who (wrongly) question whether travel is a legally protected right must recognize that voting is a fundamental right protected by law. So we might expect that voter ID laws and litigation would squarely and unavoidably pose the question of whether the exercise of rights can be conditioned on possession of ID.

Unfortunately, many of the court cases challenging voter ID laws have not reached that question. And to the extent that Circuit and District court judges have reached that question, they have been bound by bad Supreme Court precedent suggesting that even substantial restrictions on the rights of people who neither have nor are able to obtain ID are generally Constitutional. That these laws deliberately and unarguably discriminate against people without ID is not enough to make them unconstitutional, the Supreme Court majority has indicated, unless they can be shown to have been enacted with some other discriminatory intent (such as to discriminate on the basis of race, political party affiliation, or some other protected attribute). Voter ID litigation has thus been forced to focus on discrimination in the application of ID requirements, rather than their inherent illegitimacy as a precondition for the exercise of rights.

In the run-up to this year’s Presidential elections, Courts of Appeals have found such unconstitutionally racist and/or partisan discriminatory intent behind voter ID laws in North Carolina (4th Circuit), Texas (5th Circuit, en banc), and Wisconsin (7th Circuit). The election law project at the Ohio State University law school and the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU (which has been a friend of the court in some of these cases) have useful compendia of case documents and commentaries on these and other voter ID lawsuits.

These and other lawsuits challenging ID requirements to vote are continuing, but none of them are likely to be resolved by the Supreme Court until its current vacancy is filled. Any decisions by the Circuit Courts — even contradictory ones — are likely to be upheld by 4-4 vote of an equally divided Supreme Court, even if four Justices vote to review those lower court decisions. And in the meantime, any of those decisions not stayed by the lower courts themselves will presumably remain in force for the coming elections. Any application to the Supreme Court for a stay will probably also be denied by an equally divided court, as happened late last month with an application for a stay of the North Carolina ruling by the 4th Circuit.

So far, there don’t appear to be major conflicts between the Circuit Courts. Many state voter ID laws have been overturned. But the Supreme Court deadlock makes it impossible for the key Supreme Court precedent in Crawford v. Marion County Election Board (2008) to be reversed, no matter how many lower court judges write opinions urging it be reconsidered, like this one by US District Judge James D. Peterson in July of this year:

Wisconsin’s voter ID law has been challenged as unconstitutional before, in both federal and state court. In the federal case, Frank v. Walker, the Seventh Circuit held that Wisconsin’s voter ID law is similar, in all the ways that matter, to Indiana’s voter ID law, which the United States Supreme Court upheld in Crawford v. Marion County Election Board. The important takeaways from Frank and Crawford are: (1) voter ID laws protect the integrity of elections and thereby engender confidence in the electoral process; (2) the vast majority of citizens have qualifying photo IDs, or could get one with reasonable effort; and (3) even if some people would have trouble getting an ID, and even if those people tend to be minorities, voter ID laws are not facially unconstitutional. I am bound to follow Frank and Crawford, so plaintiffs’ effort to get me to toss out the whole voter ID law fails. If it were within my purview, I would reevaluate Frank and Crawford…

The Indiana law upheld by the Supreme Court in its Crawford decision required any voter who wasn’t able to show acceptable ID credentials at a polling place on election day to appear in person at the county courthouse, within 10 days after the election, to execute a declaration regarding their inability to obtain ID.

By definition, none of these people have driver’s licenses. In many cases, lack of ID and lack of mobility form a vicious circle: People can’t drive or fly without ID, but they can’t get ID without traveling to the state or city where they were born to obtain a birth certificate or other prerequisite documents. Many counties in Indiana and throughout the US have no public transit at all, while others have transit systems that serve only limited areas and routes. It’s hard to see how any court could characterize a requirement for non-drivers, especially those who reside in rural areas with no public transit, to get to the county seat during business hours (when friends or family who might be available to drive them are most likely to be working) within 10 days as only a “minimal” burden or restriction on the right to vote.

Not yet mentioned in any of these lawsuits, so far as we can tell, is the REAL-ID Act, which will make it even harder to obtain state-issued ID credentials and multiply the numbers of people disenfranchised by ID requirements for voting.

Voter ID case law, especially Crawford, doesn’t bode well for the right to travel without ID. If courts are willing to countenance such substantial restrictions on the acknowledged and clearly fundamental right to vote, they are likely to uphold even more onerous ID conditions on the exercise of rights that are less widely recognized, such as the right to travel.

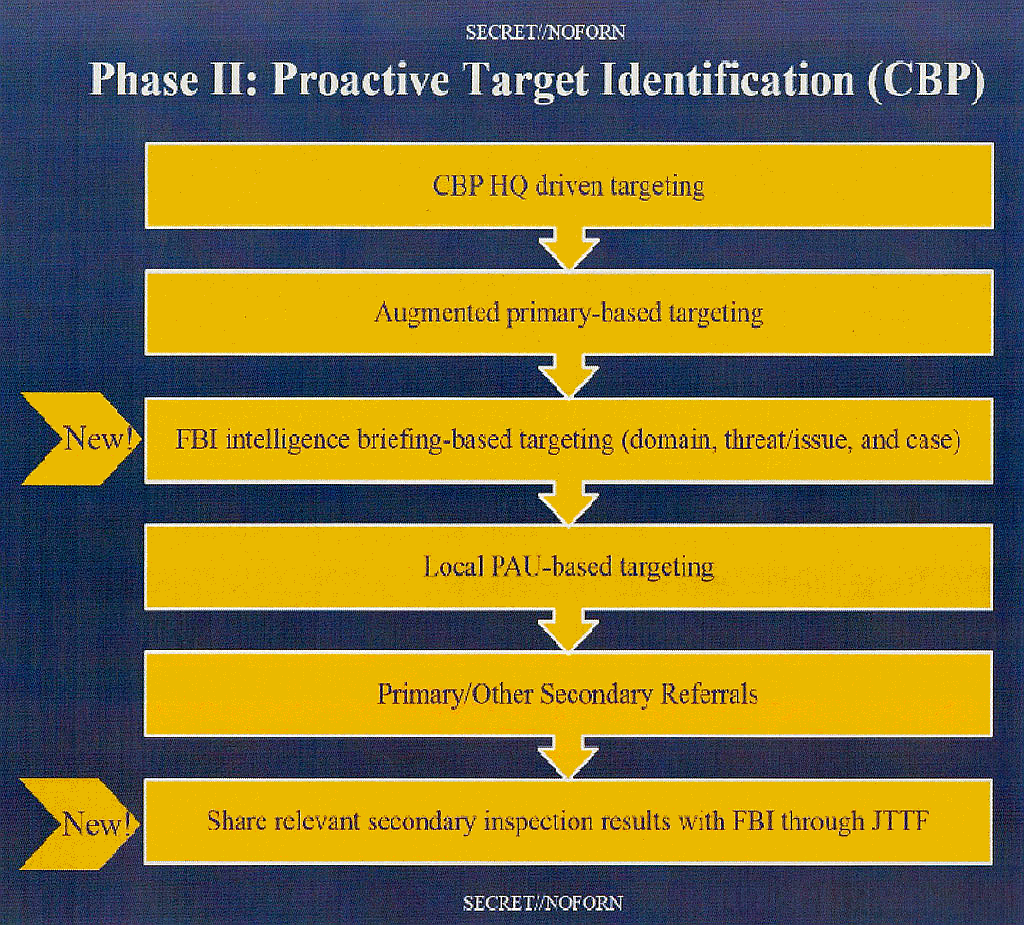

[Some of the multiple sources and types of targeting rules in the TECS algorithms used to profile international travelers, from a CBP/FBI flowchart published by The Intercept. Click on image for larger version. “PAU” = CBP Passenger Analysis Unit at a specific international airport in the USA or abroad.]

[Some of the multiple sources and types of targeting rules in the TECS algorithms used to profile international travelers, from a CBP/FBI flowchart published by The Intercept. Click on image for larger version. “PAU” = CBP Passenger Analysis Unit at a specific international airport in the USA or abroad.]