Supreme Court to review Constitutionality of warrantless police access to hotel guest logs

Today the US Supreme Court agreed to review whether — as was decided en banc by the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals last year — a Los Angeles city ordinance requiring hotel-keepers to identify guests, log their identities and the details of their hotel stays, and open those log books to police inspection at any time, without advance notice, any basis for suspicion, or a warrant or subpoena — is, on its face, in violation of the Fourth Amendment to the US Constitution.

It’s interesting that hotels are the context in which the Supreme Court has chosen to consider service providers’ Fourth Amendment objections to warrantless, suspicionless compelled police access to business transaction metadata about their customers’ identities, locations, and activities at particular times and dates. The Supreme Court has yet to accept any cases dealing with such objections by telecommunications, air transportation, or internet service providers, despite the essentially similar issues in those industries.

The key difference is that few providers of other services have challenged the government’s demands in court, as hotel owners did in the case now known at the Supreme Court as City of Los Angeles v. Patel.

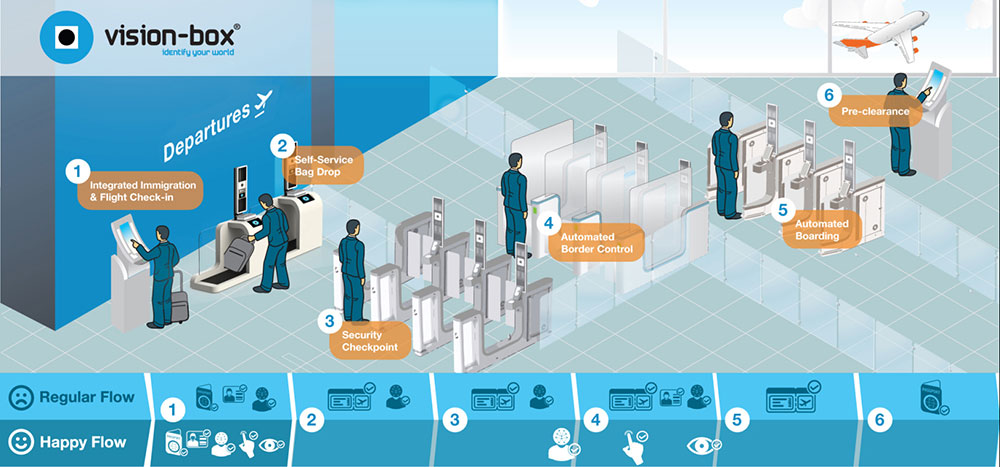

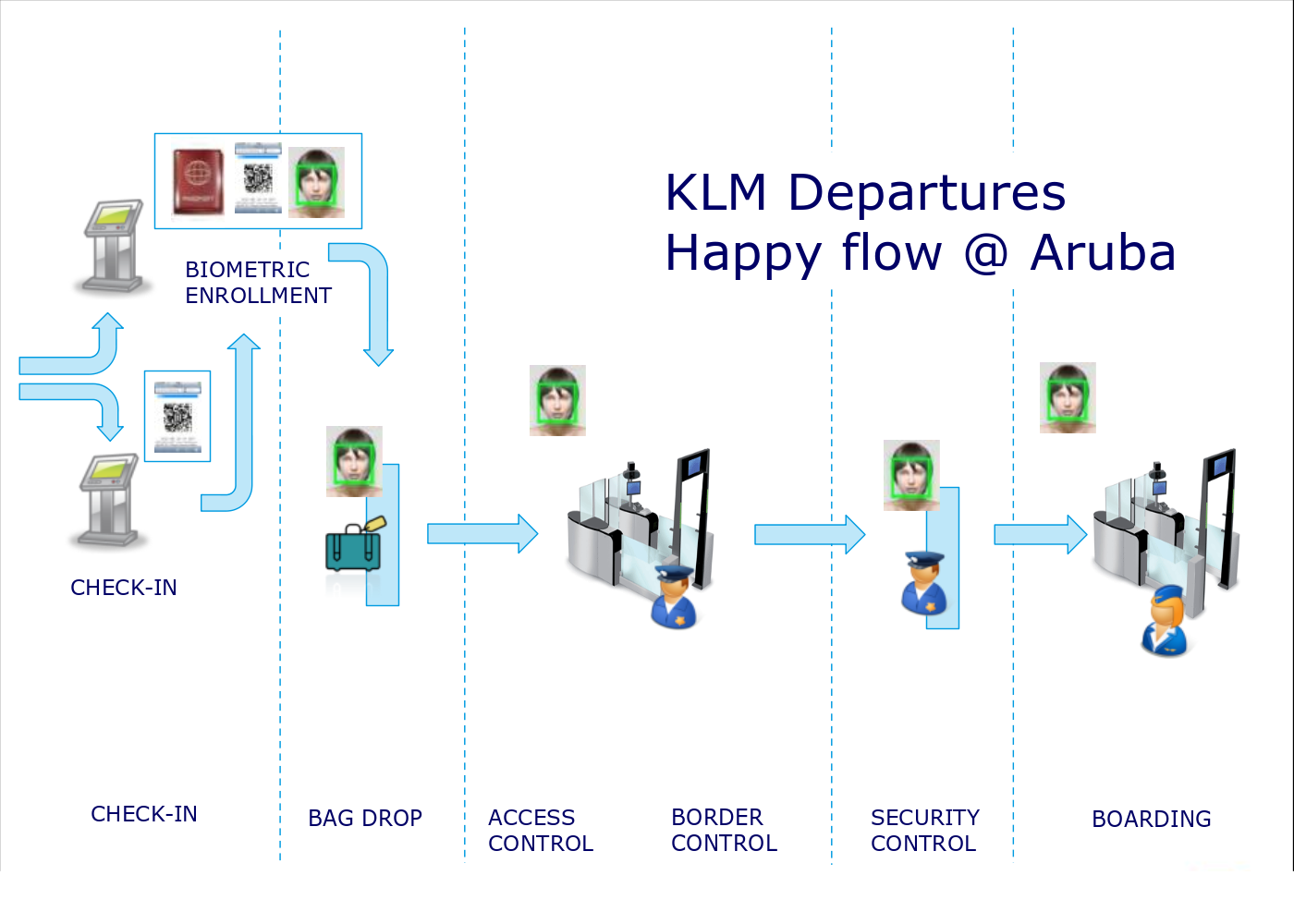

The Los Angeles hotel registry ordinance mandates exactly the same three essential elements, for example, as the Federal government’s system for outsourced dragnet surveillance and control of air travelers:

- Presentment to private service providers of government-issued ID credentials (to enable log entries to be compiled into, linked with, and mined from personal travel history dossiers).

- Recording by service providers of transaction metadata including locations, time, date, and customer ID information.

- Warrantless, suspicionless, “open book” police root access to these metadata logs at any time.

So far as we know, however, not one airline, travel agency (online or offline), or computerized reservations service (including Google, which now operates an airline reservations hosting service) has challenged any of the government’s dragnet demands for customer transaction, location, chronology, and ID metadata.

In its (successful) argument to the Supreme Court to take the case, the city of L.A. argues that state and local laws mandating identification, logging, and police access to logs of hotel guest information are “ubiquitous”, and that by the logic of the 9th Circuit decision all these laws could be found to be unconstitutional on their face. That’s true. Hotel guests (“outsiders”) have long been deemed per se suspicious persons, and hotel registry laws are among the oldest and most pervasive of (unconstitutional) laws mandating businesses to compile and maintain metadata about their customers’ and their activities and make it available to police, without warrant or suspicion for data mining or gumshoe fishing expeditions. That’s exactly why it’s so important for the Supreme Court to uphold the decision of the Court of Appeals.

The hotel owners challenged only the requirement for warrantless open-book police access to hotel registries, and not the requirements for hotels to maintain such registries or for hotel guest to show ID. That’s still an important challenge, though, and one that goes further than other businesses (certainly further than any other travel businesses) have done to defend their customers’ rights not to treated as suspects.

We continue to commend the hotel owner plaintiffs/respondents in this case for their stand. Other businesses in the travel, communications, and Internet industries could and should bring similar court challenges when they are presented with similar (and similarly unconstitutional) government demands. They cannot excuse their actions in spying on their customers by saying, “The government made us do it, and we had no choice,” if they never asked a court to rule on whether that “demand” was legally valid.