The broadest and most fundamental legal challenge to the waging of the US “War on Terror” through standardless, secret, extra-judicial government blacklists was filed today in the Federal court for the district in Virginia where the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC), Terrorist Screening Center (TSC), and Transportation Security Administration (TSA) are headquartered. (Video backgrounder and interviews with plaintiffs and attorneys; more video interviews; PACER links)

Both an individual complaint (Elhady et al. v. Piehota at al.) and a class action complaint (Baby Doe et al. v. Piehota et al.) were filed. Presumably, that is so that that the individual complaint for injunctive and declaratory relief could go forward even if class action certification is denied, while the class action lawsuit could go forward even if the named plaintiffs are delisted. (An earlier, similar lawsuit was dismissed as moot after the plaintiffs were told they were no longer on blacklists.) Almost all of the individual complaint is repeated in the class action complaint, so if you are going to read just one, read the class action complaint which includes additional plaintiffs and their stories.

The case takes its name from the first of the listed representatives of the class of people on US government blacklists (“watchlists”):

Plaintiff Baby Doe is a four year old toddler.

He was seven months old when his boarding pass was first stamped with the “SSSS” designation, indicating that he had been designated at a “known or suspected terrorist.”

While passing through airport security, he was subjected to extensive searches, pat downs and chemical testing.

Every item in his mother’s baby bag was searched, including every one of his diapers.

Let’s get one thing straight from the start: as we’ve noted before, calling the “Terrorist Screening Database” (TSDB) and similar lists “watchlists” is at best misleading euphemism, and at worst Orwellian doublespeak.

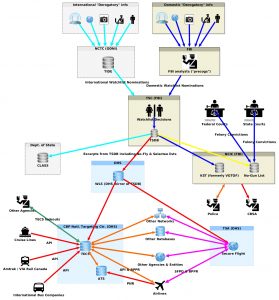

The government uses the term “watchlist” to avoid the stigma deservedly associated with the label “blacklist”, with its connotations of McCarthyism and J. Edgar Hooverism. A “watchlist” suggests a list of people who are being watched, a component of a system of surveillance or investigation. “Watchlisting” might, one presumes, lead to eventual intervention such as the criminal prosecution or an application to a court for a restraining order or injunction. But inclusion on the TSDB occurs after, not before, a decision to intervene is (secretly) made, and the consequences of listing in the TSDB are not limited to mere passive surveillance or watching. Each listing on the TSDB includes a “handling code” which determines what happens to the people who are deemed (typically by automated pattern-matching algorithms) to match the listing.

As the litany of horror stories in the complaint in Baby Doe v. Piehota makes clear, and as we’ve seen in previous incidents, being “watchlisted” can trigger consequences ranging from denial of transportation by common carriers to freezing of bank accounts, inability to rent an apartment, or inability to get or keep a job, even with a private non-governmental employer. As when a jury must decide which of a progression of more and less serious offenses to convict a defendant of, without knowing what sentences are mandated for any of those offenses, it’s not clear whether the Federal administrative staff in the secret rooms reviewing the secret dossiers of derogatory information and deciding which secret lists to put people on, or which secret “action codes” to assign them, even know what the full panoply of collateral consequences of their decisions will be.

The US government doesn’t have to issue binding orders to convert “watchlisting” into de facto blacklisting. As the complaint filed today points out, “Defendants disseminated the the records pertaining to Plaintiffs from its terrorist watch list to foreign governments with the purpose and hope that those foreign governments will constrain the movement of the Plaintiffs in some manner.” We saw one of the ways that can work during the trial of Dr. Rahinah Ibrahim’s challenge to her placement on the no-fly list. The US government successfully used a “POSSIBLE NO BOARD REQUEST” message to induce a foreign airline to refuse to transport Dr. Ibrahim’s daughter, a US citizen, even though the US claimed that she was merely on a “watchlist” and not on the no-fly list.

It’s time to to reject the government’s “watchlist” doublespeak, and start calling the TSDB what it is: a government blacklist.

The first of the named defendants, Christopher Piehota, is the Director of the Terrorist Screening Center (TSC), an inter-agency entity responsible for the TSDB and nominally under the control of the FBI.

Most of the previous attempts to challenge actions taken against individuals as a result of their being listed in the TSDB have foundered on an elaborate shell game of buck-passing between businesses and government agencies. Airlines that refuse to transport blacklisted people (or those with similar names) say that they are only following (secret) orders from the government. Normal judicial review of actions by the TSA and CBP, the components of the DHS that issue no-fly orders (or refuse to issue permission for boarding pass issuance — the default is now “No,” not “Yes”) is precluded by a special law, 49 U.S.C. § 46110. No trials are allowed, and appellate courts are allowed to review these decisions only on the basis of the “administrative record” created by the DHS itself, which will show only that the DHS action was based on “watchlist” status as determined by the TSC, and not the basis (if any) for the FBI’s “watchlisting” decision.

The only previous cases in which District Courts have been able to consider no-fly decisions, and the only trial in a no-fly lawsuit, have been when the FBI, and not just the DHS or DHS components, has been named as a defendant. Today’s cases follow in that line, challenging the blacklisting decisions by the FBI.

To head off lawsuits of exactly this sort, the government has recently shifted nominal final authority over no-fly decisions from the FBI to the TSA. In theory, the government claims, the TSA could now decline to issue a no-fly order, even after the FBI has put someone on the no-fly list. It’s unclear, however, whether this has ever happened, or in what circumstances or on what basis it might happen. The possibility seems remote: Even the FBI, in practice, acts as a rubber-stamp for the decisions of FBI and DHS agents who make effectively final blacklisting decisions when they “nominate” people for listing in the TSDB. According to today’s complaint, 98.96% of the 468,749 people “nominated” for Federal “watchlists” in 2013 were added to those lists by the TSC.

The plaintiffs in the lawsuits filed today are represented by Gadeir Abbas, Lena Masri, and co-counsel from the Council on American-Islamic Relations, who have been leading the legal campaign against US government blacklisting, harassment, and interference with the rights and freedoms of Muslim and other Americans.