“No-fly” trial, day 2: Dr. Ibrahim gets her (virtual) day in court

Dr. Rahinah Ibrahim’s lead counsel, Elizabeth Pipkin, opened the second day of trial of Dr. Ibrahim’s lawsuit against the government for putting her on its “no-fly” list without due process with an update on Dr. Ibrahim’s eldest daughter, U.S.-born U.S. citizen Rainan Mustafa Kamal, who was denied permission by the DHS to board a flight to the U.S. on Sunday to attend and testify at the trial in her mother’s lawsuit.

Ms. Pipkin reminded the court of what government counsel Paul Freeborne of the Department of Justice told the court before the trial recessed on Monday:

Freeborne: Your Honor, we’ve confirmed that the defendants did nothing to deny plaintiff’s daughter boarding. It’s our understanding that she just simply missed her flight. She has been re-booked on a flight tomorrow. She should arrive tomorrow.

“None of that was true,” Ms. Pipkin told the court this morning. “She didn’t miss the flight. She was there in time to check in. She has not been rebooked on another flight.” And most importantly, it was because of actions by the DHS — one of the defendants in Dr. Ibrahim’s lawsuit — that Ms. Mustafa Kamal was not allowed to board her flight to SFO to attend and testify at her mother’s trial.

Ms. Pipkin said that Ms. Mustafa Kamal had sent her a copy of the “no-board” instructions which the DHS gave to Malaysia Airlines, and which the airline gave to Ms. Mustafa Kamal to explain as much as it knew about why it was not being allowed to transport her. Ms. Pipkin handed Judge William Alsup a copy of the DHS “no-board” instructions to Malaysia Airlines regarding Ms. Mustafa Kamal.

Major props to Malaysia Airlines for providing a copy of the DHS instructions to Ms. Mustafa Kamal. Other airlines receiving similar instructions have acquiesced to DHS orders to keep the instructions from the DHS, and the reasons for the airlines’ actions, secret from the would-be travelers whose rights are affected. So far as we know, this is the first time an actual no-fly order has been disclosed to a would-be traveler or potentially to the public.

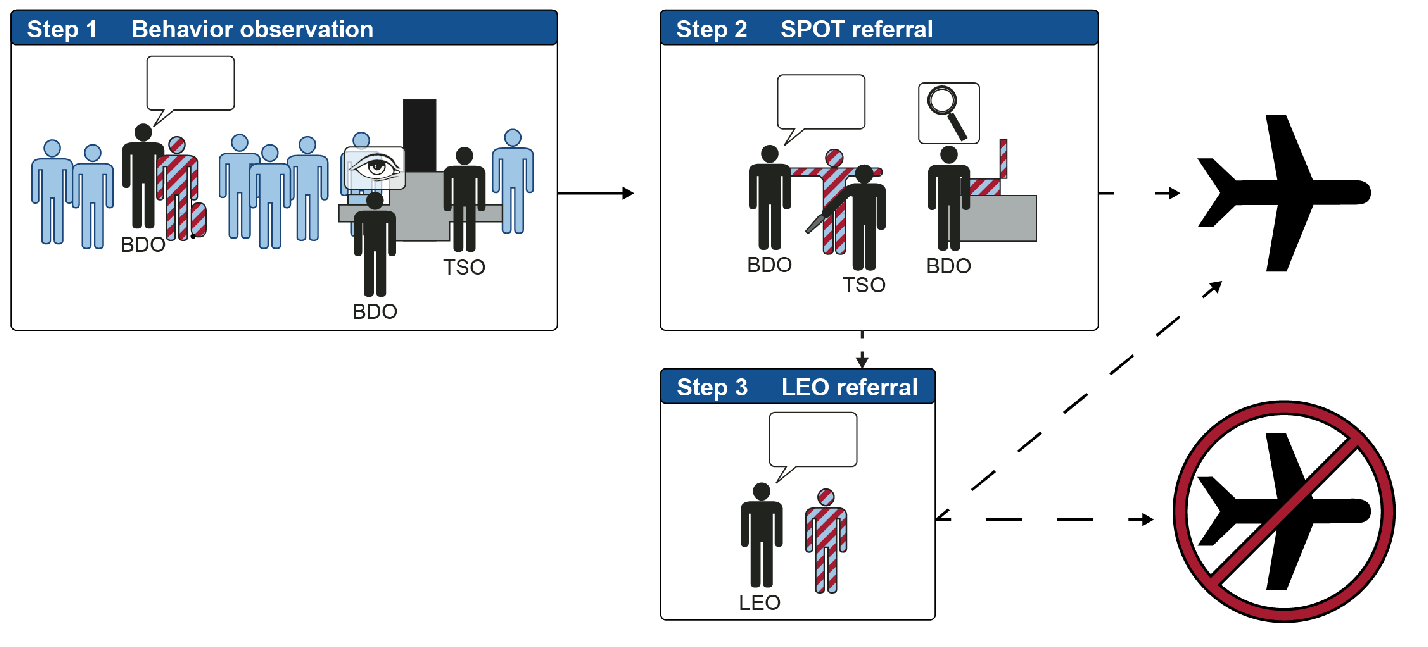

International airlines are required to send a complete copy of each Passenger Name Record (PNR) to the CBP division of DHS, which processes PNRs through a black box to which one of the inputs is the set of U.S. government “watchlists”. [The term used throughout the trial was, “watchlist”. But these lists aren’t used solely as a “watching” or surveillance tool. They are also used as the basis for “no-board” orders to airlines, and other actions. We think “blocking lists” or “blacklists” would be more accurate labels for these lists.]

If the would-be traveler is “cleared” by this process (the default is, “No”), CBP responds by sending an individualized permisison message in the form of an electronic “boarding press printing result”. (Diagrams and video explaining this process.) Presumably, the page-long DHS message to Malaysia Airlines was some sort of supplement or follow-up to a “not cleared” boarding pass printing result regarding Ms. Mustafa Kamal.

It would have been one thing for the ten government lawyers in Judge Alsup’s courtroom to claim that they “had no knowledge” of any DHS actions to interfere with Ms. Mustafa Kamal’s flight to the U.S. and appearance at the trial. But the government went much further when Mr. Freeborne claimed that the government had “confirmed” that the DHS did nothing to deny Ms. Mustafa Kamal boarding.

But Judge Alsup noted that the document with the DHS instructions to the airline was not supported by any sworn testimony or evidence of its authenticity. “You have to have a sworn record before I can do something dramatic.” Judge Alsup said he would consider the document if and when Ms. Mustafa Kamal arrives in San Francisco and can testify as to its authenticity.

Ms. Pipkin said that Ms. Mustafa Kamal was reluctant to spend the money on another airline ticket to San Francisco without some assurance that this time she would be allowed to board her flight.

“Get her on an airplane and get her here,” Judge Alsup responded. “She’s a U.S. citizen. She doesn’t need a visa. I’m not going to believe that she can’t get on a plane until she tries again. ” And Mr Freeborne, with disingenuous faux-solicitude, claimed that the government is “willing to do whatever we can to facilitate” Ms. Mustafa Kamal’s ability to board a flight to the U.S.

Judge Alsup wasn’t willing to take any action today on unproven allegations or unverified documents. But he made clear that, “I am disturbed by this…. We’ll hear from her [Ms. Mustafa Kamal] when she gets here. If it turns out that the DHS has sabotaged a witness, that will go against the government’s case. I want a witness from Homeland Security who can testify to what has happened. You find a witness and get them here.”

Following these and a few other preliminaries, Ms. Ibrahim’s lawyers resumed playing excerpts from her deposition, recorded on video in London (because the defendants won’t allow her to come to the U.S. to testify in person) in July 2013.