DHS continues to threaten states that resist the REAL-ID Act

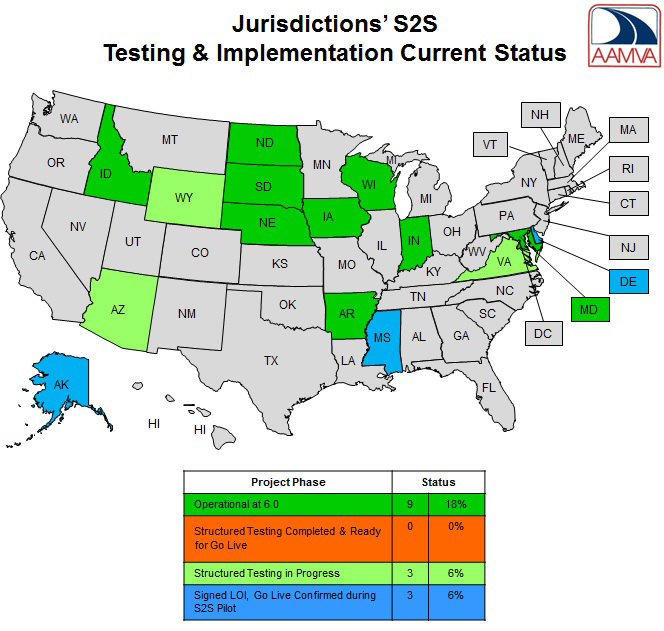

[Status of REAL-ID compliance as of October 17, 2016 (Source: AAMVA.org)]

[Status of REAL-ID compliance as of October 17, 2016 (Source: AAMVA.org)]

Last week the Department of Homeland Security denied requests by five states for “extensions” of time to comply with the REAL-ID Act of 2005. The DHS denials of requests for extensions were accompanied by renewed threats of restrictions on residents of those states: “Starting January 30, 2017, federal agencies and nuclear power plants may not accept for official purposes driver’s licenses and state IDs from a noncompliant state/territory without an extension,” said DHS spokesman Aaron Rodriguez in a statement.

Does this mean that a deadline is approaching? That every state except these five has “complied” with the REAL-ID Act? That these “holdouts” have no choice but to comply? That the sky will fall on these states, or their residents, if they don’t?

No, no, no, and no.

As we told the Washington Times:

Not everyone thinks states will, or should, be swayed by the federal government’s determination.

“These are not states that stand out because they are less compliant,” said Edward Hasbrouck, a spokesman for the privacy advocacy group The Identity Project.

He says Homeland Security is arbitrarily enforcing aspects of the Real ID Act by deeming states compliant even when they have not met every requirement, noting specifically few “compliant” states have met the requirement that they provide access to information contained in their motor vehicle database via electronic access to all other states.

“It’s a game of chicken, it’s a game of intimidation, and very little of it has to do with actual requirements or actual deadlines,” Mr. Hasbrouck said.

If Homeland Security, which repeatedly has pushed back compliance deadlines for Real ID, does go through with the commercial airline restrictions in 2018, Mr. Hasbrouck said he expects grounded passengers would eventually bring litigation challenging the law.

Let’s look at some of the questions skeptical citizens and state legislators ought to be asking about these DHS scare tactics:

-

- How many states have complied with the REAL-ID Act? Noncompliant states are neither alone nor isolated. According to the Washington Times, “Homeland Security reports that 23 states and Washington, D.C., have met enough of the Real ID standards to be deemed in compliance with the law.” In fact, as we’ve reported previously and as we noted in the comments above, the most significant component of compliance with the REAL-ID Act is participation in the national ID database (the one the DHS keeps claiming doesn’t exist). That database, called SPEXS, is operated by a subcontractor to the American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators (AAMVA) as a component of its S2S system. When last we checked, in February of this year, only 4 of 55 US jurisdictions (states, the District of Columbia, and US territories) had connected their state drivers license and ID databases to S2S. With the addition of the latest two states this month, the total of states participating in S2S is up to nine, as shown on the AAMVA map at the top of this article. We don’t know whether all nine of those states have implemented all the other requirements of the REAL-ID Act. But we do know that no state not participating in S2S is in compliance. So at most nine states are in compliance with the REAL-ID Act. The vast majority of jurisdictions are noncompliant. And at this rate, it will take many years, if it ever happens at all, for the DHS to whip the rest of them into line.

-

- When is the deadline for states to comply with the REAL-ID Act? There is no deadline for compliance in the law itself. The DHS could set deadlines by promulgating regulations, but it could also change them in the same way, at any time, for any reason. In practice, the current DHS threats aren’t event based on DHS regulations, but on dates specified solely in DHS press releases and changeable at DHS whim.

-

- What is required for DHS certification of material compliance or progress toward compliance by individual states? There are no criteria in the law. The law leaves this up to the “discretion” of the DHS, which in practice means that it can be standardless, secret, and arbitrary. DHS choices of which states to threaten are political and tactical choices about which states the DHS thinks it can intimidate, and in which order. They aren’t based, or required to be based, on any actual measurement, checklist, or relative degree of compliance.

- What will happen, and when will it happen, to residents of states that don’t comply sufficiently or quickly enough? Probably nothing. What the DHS will try to do, and when, is once again totally up to its discretion. There are no deadlines in the law. But as our analysis and the responses to our FOIA requests have shown, the threat to deny access to Federal facilities is a red herring. Most workers at these facilities, for example, already have Federally-issued employee IDs, and don’t rely on state-issued IDs for entry. Members of the public generally enter these facilities to exercise various of their rights, which the DHS recognizes they have a right to do without any ID. If the DHS changes its tune, and tries to interfere with those rights, what the DHS can get away with will be determined by Federal judges in the inevitable lawsuits brought by residents of disfavored states (hopefully with the support of state governments) whose rights are interfered with on the basis of the REAL-ID Act.