Show ID or pay a fee to attend a “public” meeting?

Is it an “open” meeting if you have to identify yourself, show ID, and/or pay a fee to attend?

That’s the question presented by today’s meeting of the Minneapolis-St. Paul Metropolitan Airports Commission (MAC), which is scheduled to be held in the “secure” area of the MSP airport reachable only by passing through the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) checkpoint.

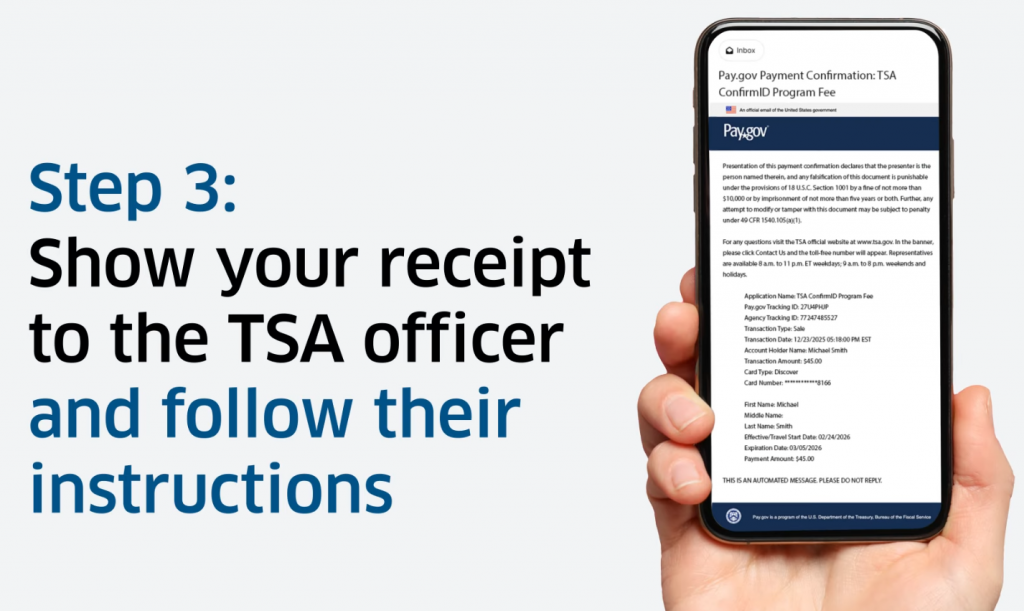

As of February 1, 2026, this means individuals who want to attend a MAC meeting, including those who want to make public comments and those who just want to observe, must either (A) show ID credentials the TSA finds satisfactory or (B) pay the illegal $45 per person TSA Confirm.ID fee, answer whatever questions the TSA asks (based on records of the Accurint data broker), and be “allowed” by the TSA, in its unreviewable and arbitrary discretion, to enter the secure area of the airport. The MAC website says that “the MAC will cover this cost for up to three meetings”, but doesn’t say what will happen after that.

This is the first time — in Minnesota or any other state — that we have seen a demand for ID, a demand for a fee, a limit on the number of meetings that can be attended without a fee, or delegation of authority (authority the MAC itself would lack) to an independent third party to demand answers to questions or to decide in its discretion who to allow to attend a meeting of a government body required by law to be open to the public.

Is any of this legal? We doubt it.

Rules for meetings of government decision-making bodies vary by state. The MAC is a Minnesota state agency whose members are appointed by the Governor. The Minnesota Open Meeting Law (Minnesota Statutes Chapter 13D) requires that all decision-making meetings of entities such as the MAC “must be open to the public”.

The Minnesota law doesn’t define what “open to the public” means, but we don’t think it includes any of these conditions and restrictions on attendance:

- Requiring individuals to identify themselves (rather than attending anonymously, as they may wish to do if e.g. they fear retaliation for attending or making public comments).

- Requiring individuals to have or show ID credentials.

- Requiring individuals to answer questions including questions from a third party (in this case, the TSA).

- Require individuals to pay a fee, or limiting the number of open meetings an individual may attend without paying a fee. (In this case, the fee is patently illegal, and having agreed to pay the fee on behalf of individuals attending MAC meetings, the MAC itself would have standing to challenge the fee.)

- Granting a third party discretion to decide who will, and who will not, be allowed to attend a meeting. (The MAC website notes that “Verification is not guaranteed”, i.e that the TSA may choose not to allow an individual to pass through the checkpoint, even if they identify themselves verbally, pay the $45 fee or have it paid for them, and answer all of the TSA’s questions.)

None of this fits within any reasonable definition of “open to the public”.

Any member of an entity subject to the Minnesota Open Meetings Law who violates this law, including by attending a business meeting of an agency that isn’t open to the public, is personally liable for a $300 fine for each “occurrence”. They have to pay the fine themselves. The agency isn’t allowed to pay it for them. Under a “three strikes you’re out” provision of this law, any office-holder found guilty of three separate violations of the Open Meetings Law forfeits their office for the remainder of their term.

Meanwhile, we’re still waiting for a full response to our request under the Minnesota Government Data Practices Act for information about the basis for the MAC’s dubious claim that it lacks any authority to limit where in the airport Federal agents can go.

The last word we received is that we can expect a response to our public records request tomorrow — the day after the monthly MAC meeting today at which we and others might (if we were allowed by the TSA to attend) have asked questions of MAC members about the decision to give Federal agents free run of the airport without challenge.