The complete unredacted decision in favor of Dr.. Rahinah Ibrahim issued by U.S. District Judge William Alsup in January, following the first trial in any case challenging a US government “no-fly” order, was finally made public today by order of the court. (Unredacted version as unsealed; version with previously redacted portions highlighted.) The deadline for any appeal has passed, and this order is now final.

Despite the government’s claims that the redactions were of vital “state secrets”, the formerly-redacted portions of the decision, and the declarations filed yesterday by the government, shed relatively little new light on what happened to Dr. Ibrahim and her family. They do, however, contain a previously-redacted chronicle of her having been placed on and off various “watchlists” (de facto blacklists) while her lawsuit was pending, and of a previously unmentioned exception to the nonbinding “standards” for watchlisting:

45. To repeat, government counsel have conceded at trial and this order finds that Dr. Ibrahim is not a threat to the national security of the United States. She does not pose (and has not posed) a threat of committing an act of international or domestic terrorism with respect to an aircraft, a threat to airline passenger or civil aviation security, or a threat of domestic terrorism.

46. In March 2005, Dr. Ibrahim filed a Passenger Identity Verification Form (PIVF) (TX 76). [This was a predecessor to the DHS-TRIP form.]

47. In December 2005, Dr. Ibrahim was removed from the selectee list. Around this time, however, she was added to TACTICS (used by Australia) and TUSCAN (used by Canada). No reason was provided for this at trial.

48. On January 27, 2006, this action was filed.

49. In a form dated February 10, 2006, an unidentified government agent requested that Dr. Ibrahim be “Remove[d] From ALL Watchlisting Supported Systems (For terrorist subjects: due to closure of case AND no nexus to terrorism)” (TX 10). For the question “Is the individual qualified for placement on the no fly list,” the “No” box was checked. For the question, “If no, is the individual qualified for placement on the selectee list,” the “No” box was checked.

50. In 2006, the government determined that Dr. Ibrahim did not meet the reasonable suspicion standard. On September 18, 2006, Dr. Ibrahim was removed from the TSDB. The trial record, however, does not show whether she was removed from all of the customer watchlists subscribing to the TSDB.

51. In a letter dated March 1, 2006, the TSA responded to Dr. Ibrahim’s PIVF submission… The response did not indicate Dr. Ibrahim’s status with respect to the TSDB and no-fly and selectee lists.

52. One year later, on March 2, 2007, Dr. Ibrahim was placed back in the TSDB. The trial record does not show why or which customer watchlists were to be notified.

53. Two months later, however, on May 30, 2007, Dr. Ibrahim was again removed from the TSDB. The trial record does not show the extent to which Dr. Ibrahim’s name was then removed from the customer watchlists, nor the reason for the removal.

54. Dr. Ibrahim did not apply for a new visa from 2005 to 2009. In 2009, however, she applied for a visa to attend proceedings in this action. On September 29, 2009, Dr. Ibrahim was interviewed at the American Embassy in Kuala Lumpur for her visa application.

55. On October 20, 2009, Dr. Ibrahim was nominated to the TSDB pursuant to a secret exception to the reasonable suspicion standard. The nature of the exception and the reasons for the nomination are claimed to be state secrets. In Dr. Ibrahim’s circumstance, the effect of the nomination was that Dr. Ibrahim’s information was exported solely to the Department of State’s CLASS database and the United States Customs and Border Patrol’s TECS database.

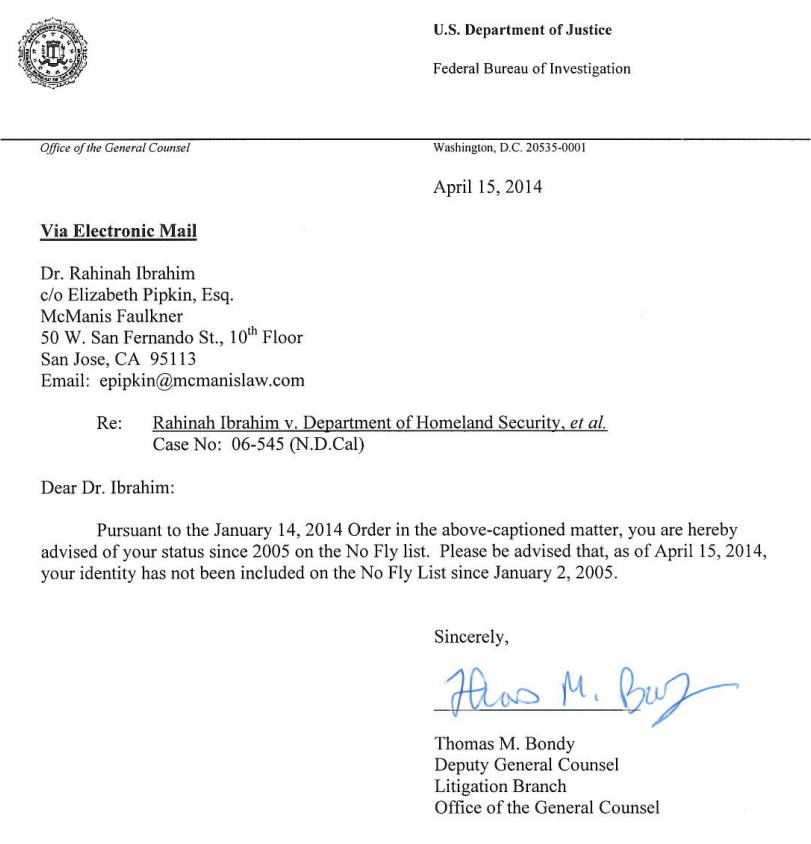

56. From October 2009 to present, Dr. Ibrahim has been included in the TSDB, CLASS, and TECS. She has been off the no-fly and selectee lists….

60. On December 14, 2009, Dr. Ibrahim’s visa application was denied….

64. The TSC has determined that Dr. Ibrahim does not currently meet the reasonable suspicion standard for inclusion in the TSDB. She, however, remains in the TSDB pursuant to a classified and secret exception to the reasonable suspicion standard. Again, both the reasonable suspicion standard and the secret exception are self-imposed processes and procedures within the Executive Branch.

65. In September 2013, Dr. Ibrahim submitted a visa application so that she could attend the trial on this matter…. Trial in this action began on December 2 and ended on December 6. As of December 6, Dr. Ibrahim had not received a response to her visa application. At trial, however, government counsel stated verbally that the visa had been denied. Plaintiff’s counsel said that they had not been so aware and that Dr. Ibrahim had not been so notified….

70. Since 2005, Dr. Ibrahim has never been permitted to enter the United States.

The other most significant remaining questions concern Dr. Ibrahim’s daughter, Ms. Raihan Mustafa Kamal, who was born in the US and is a US citizen, but was prevented from flying to the US to observe and testify at her mother’s trial. (Previous reporting about Ms. Mustafa Kamal here, here, and here.)

According to a section of Judge Alsup’s decision (pp. 24-25) about Ms. Mustafa Kamal that was previously redacted in its entirety:

On December 1 [2013], the National Targeting Center (“NTC”) within the Department of Homeland Security began vetting passengers for the Philippine Airlines flight. NTC officers determined that Ms. Kamal was matched to a record that was listed in the TSDB in a category which notifies the Department of State and Department of Homeland Security that other government agencies may be in possession of substantive “derogatory” information about the individual that may be relevant to an admissibility determination under the Immigration and Nationality Act. United States citizens, of course, are not subject to the admissibility provisions of the Immigration and Nationality Act….

On December 2, Ms. Kamal’s records were updated in the TSDB to reflect that she was a United States citizen. The request for additional screening was rescinded and it was requested that Ms. Kamal be allowed to board without delay.

Since Ms, Mustafa Kamal was not a party to her mother’s case (although the government had been notified that she was a potential witness), the issues related to her were not pursued or resolved in that case.

So we still don’t know what “derogatory” information would be relevant to the “admissibility” to the US of a US citizen, or why DHS is keeping records of such information or “watchlisting” such individuals.

Also today, Judge Alsup ruled that the government must pay some, but not all, of Dr. Ibrahim’s legal fees and costs. The exact amount remains to be determined by a special master. Judge Alsup found that the government had been “unreasonable” in many of its actions and arguments, but had not been shown to have acted in bad faith.

As we’ve previously reported, other no-fly cases are moving forward, with that of Gulet Mohamed (currently in the early stages of discovery in Disctrict Court on remand following denial by the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals of the government’s motions to dismiss) likely next in line for trial.