TSA statements to court reviewing interrogations of travelers

In a filing with the Court of Appeals reviewing a TSA mandate for airlines to interogate passengers on international flights before allowing them to board, the TSA has directly contradicted previous explicit written statements by an official TSA spokesperson as to whether passengers are required by the TSA to answer questions from airline staff about their travel purposes as a condition of being allowed to fly.

Equally if not more disturbingly, the TSA also claimed in the same filing with the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals that an airline licensed by the US government to operate as a common carrier has “independent discretion to deny boarding to any passenger about whom they have a concern.”

In an email message in January of this year to “professional troublemaker” and frequent traveler Jonathan Corbett, the TSA “Office of Global Strategic Communicationsa Desk” said:

American Airlines is required to conduct a security interview with passengers prior to departure to the United States from an overseas last point of departure airport. If a passenger declines the security interview, American Airlines will deny the passenger boarding. The contents of the security program and the security interview are considered Sensitive Security Information (SSI).

But when Mr. Corbett petitioned the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals to review the TSA’s secret orders to airlines containing this mandate, the TSA filed the following statement with the court:

Interviews are … intended only to determine screening protocols before a passenger may fly. TSA does not direct U.S. aircraft operators to refuse to carry a passenger who declines participation in the interview process.

This isn’t the first time the TSA has told Federal judges that official TSA notices and public statements about what air travelers are “required” to do, as a condition of being “allowed” to exercise our right to travel, are false.

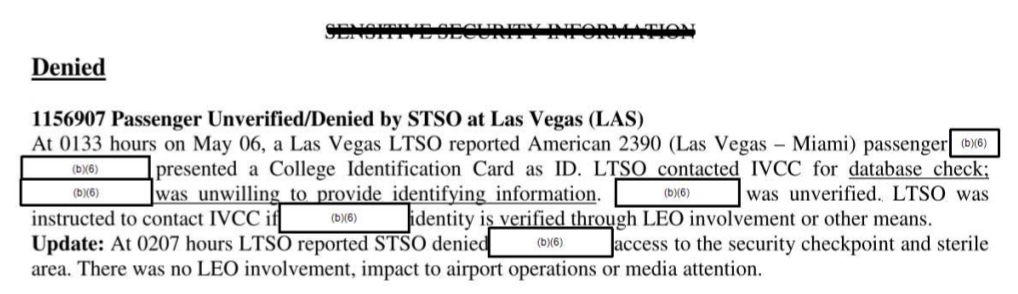

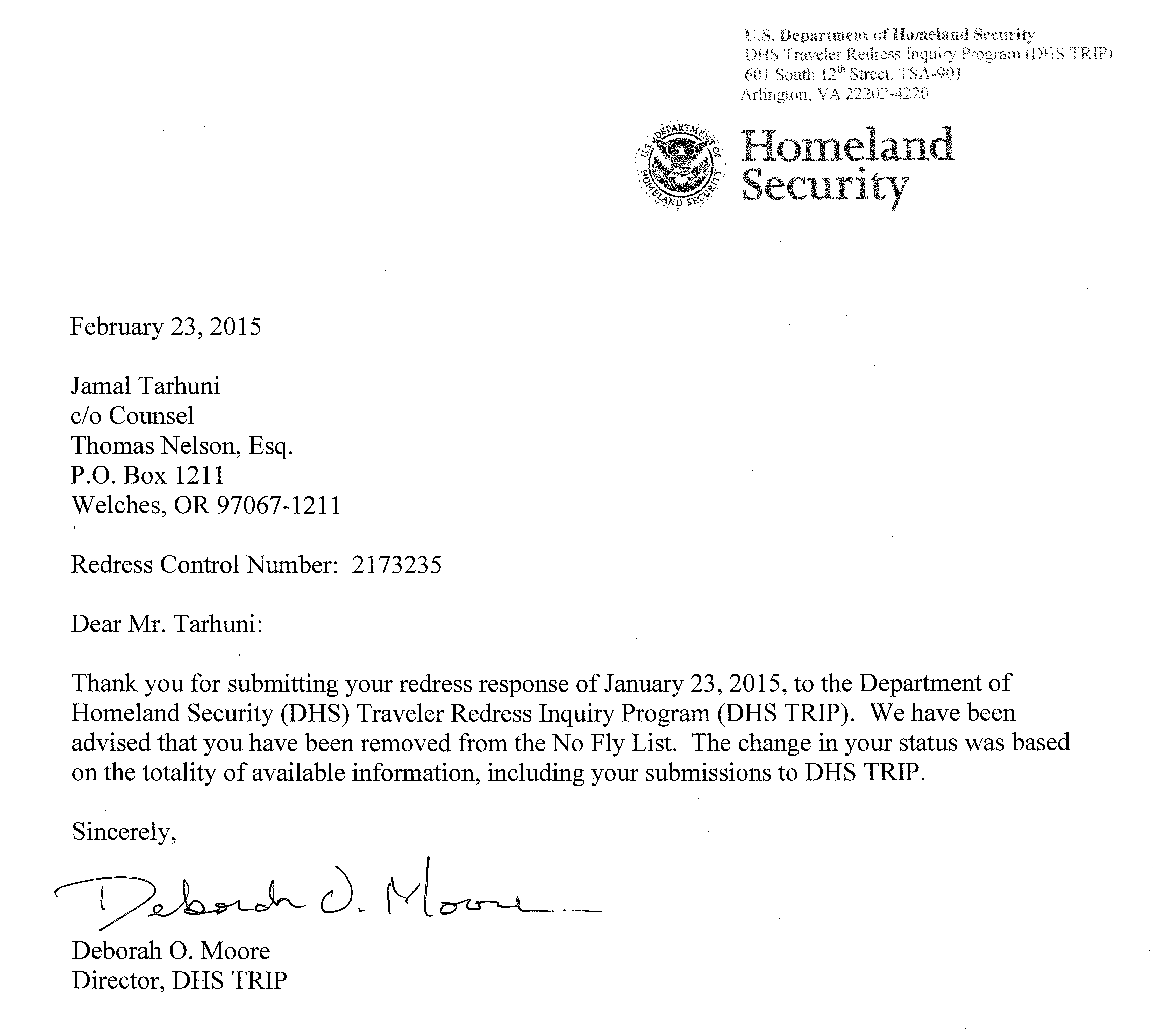

In 2006, the TSA told the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals panel reviewing the requirement for air travelers to show government-issued ID credentials in Gilmore v. Gonzalez that there is no such TSA requirement in the secret TSA security directives to airlines, despite notices still posted at TSA checkpoints (and, at the time, on the TSA website) that passengers are required to show ID. Most people who are unable and/or unwilling to show ID are allowed to fly, although some aren’t. There are no rules or publicly-disclosed criteria for who the TSA does or does not allow to fly. The TSA’s orders to the airlines, and the airline policies approved by the TSA, are secret.

At a minimum, the TSA’s repeated disavowals in court of what it has publicly claimed or implied are TSA requirements mean that travelers cannot resoanably be expected to believe or rely on those official but not legally beinding TSA statements, and have good cause to demand that TSA explicitly state whether anything they ask is a legally-binding TSA “order”, a request, or an airline or or other private demand not mandated by the TSA. Noncompliance with requests not explicitly identified by TSA staff as TSA orders cannot reasonably construed as interference with, or refusal to submit to, TSA requirements.

The only way to reconcile the TSA’s statement to the court that “TSA does not direct U.S. aircraft operators to refuse to carry a passenger who declines participation in the interview process” with the agency’s previous statement to the public that, “If a passenger declines the security interview, American Airlines will deny the passenger boarding,” is that the airline — on its own initiative and inidepndently of the TSA-mandated and TSA-approved “security program” — has committed to the TSA that it will deny boarding to anyone whoi declines to answer the airline’s questions about their travels.

That possible interpretation is supported by the TSA’s further statement to the Court of Appeals:

While … carriers retain their independent discretion to deny boarding to any passenger about whom they have a concern, whether as a result of an interview or otherwise, that outcome is not dictated by the international security interview program.

The problems with this — aside from the TSA’s misleading statements to the public about the source of this “requirement” — are that an airline, by law, has no such discretion, and that the TSA is required by law (49 USC § 40101) to “consider … the public right of freedom of transit through the navigable airspace” in carrying out its responsibilities including approving airline policies.

The duty of the TSA, if it becomes aware of an airline policy or practice to exercise such unlawful “discretion” or claim the “right to refuse service”, is to disapprove the policy or practice. If an airline persists in such a practice, the duty of the TSA is to order the airline to discontinue to the practice or, if that is outside the TSA’s jurisdiction, to refer the airline to the Department of Transportation for the imposition of sanctions, which ultimately could include the revocation of the airline’s certification from the DOT to operate as a common carrier.

It’s bad enough that airlines are trying unilaterally to abrogate their responsibilities as common carriers. It’s far worse that the government is acquiescing in, much less encouraging, such practices.