Edward Hasbrouck of the Identity Project will be speaking at a free, public forum on Travel Surveillance, Traveler Intrusion from noon-1 p.m. EDT next Tuesday, 2 April 2013, at the Cato Institute in Washington DC (with a live webcast):

Travel Surveillance, Traveler Intrusion

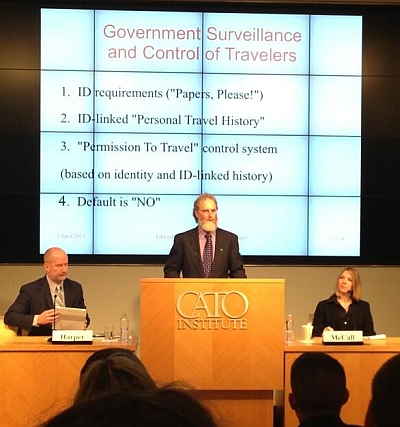

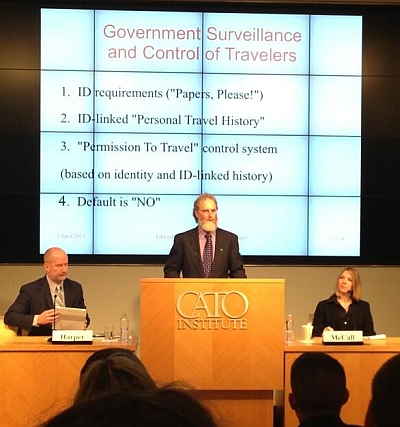

[photo by kind permission of Jeramie D. Scott]

Featuring Edward Hasbrouck, Journalist, Consumer Advocate, Travel Expert, and Consultant, The Identity Project (PapersPlease.org), Author of the book and blog, The Practical Nomad; and Ginger McCall, Director, Open Government Program, Electronic Privacy Information Center; moderated by Jim Harper, Director of Information Policy Studies, Cato Institute.

The United States government practices surprisingly comprehensive surveillance of air travel, amassing data about the comings and goings of all Americans who fly. Travel expert Edward Hasbrouck has been researching travel surveillance for many years. His findings reveal a stunning level of government surveillance, control of the traveler, and intrusion into commercial travel IT systems.

By April 2, the Transportation Security Administration will have begun a public comment process on its policy of putting travelers through imaging machines that can see under their clothes. Ginger McCall of the Electronic Privacy Information Center has been handling the litigation that prompted the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals ruling requiring it to do so, and she will assess the proposed regulation and her renewed efforts to bring the TSA within the law.

If you can’t make it to the Cato Institute, watch this event live online at www.cato.org/live.

The Cato Institute asks that you pre-register if you plan to attend in person, but that’s just so they have an estimate of the expected attendance.

Hasbrouck will be presenting examples of what he found in his files when he sued the DHS for its records of his travels, what other travelers have found in theirs, and how the DHS obtains and uses this information to track us and to control who is allowed to travel.

As part of the same program, Ginger McCall of EPIC will be discussing the TSA’s proposed “rules” to require all air travelers to submit to virtual strip-searches. You have 90 days, until 24 June 2013, to tell them what you think of their proposal. (On the form to submit comments to the TSA, note that all of the fields except your comment itself are optional.) You can find some ideas for what to say in our previous article about the rulemaking.

There will be a live webcast, for those who aren’t in DC.

If you’d like to follow along, you can download the slides from Hasbrouck’s presentation as a PDF file.

[Update: C-SPAN broadcast the event live. Streaming video is available from the Cato Institute event archives (recommended), the C-SPAN archives, or on Youtube. The C-SPAN and Youtube camera angles don’t show the slides which illustrate Hasbrouck’s talk, so we recommend watching the Cato version and/or downloading the slides to follow along with the talk on C-SPAN. If you want to find out what’s in the file about you in the DHS “Automated Targeting System”, you can use the forms here. We would welcome a chance to review the government’s response, if you get one, and help you interpret it.]