If your travel history is “suspicious”, is that cause for search?

If the file about you the DHS has compiled from airline reservations, license-plate readers, and other travel surveillance data sources is deemed “suspicious”, does that constitute probable cause for a search of your home and business or seizure of your possessions?

That question has arisen in the case of Albuquerque antique gun collector and dealer Bob Adams, argued in May 2015 and currently awaiting a decision by the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals in Denver.

On January 23, 2013, Mr. Adams’ home and business was raided by a SWAT team including DHS and other Federal and state agencies. Various of his possessions, including his collection and inventory of firearms, were seized, damaged, and/or destroyed in the raid. On November 4, 2013, after Mr. Adams had filed suit to recover his property, he was indicted for various technical violations of Federal laws relating to firearms imports and dealer licensing and reporting.

Both the search warrant and the indictment were based, in part, on allegations by Federal law enforcement officers regarding the records of Mr. Adams’ international travel history in the DHS Automated Targeting System (ATS). In an affidavit supporting the application to a Federal magistrate for the search of Mr. Adams’ home and business, “Special Agent” Frank Ortiz of the New Mexico Attorney General’s Office claimed that ATS records showed that Mr. Adams had repeatedly flown to Canada without having return flight reservations to the US, and had subsequently re-entered the US as a passenger in a private car. This, agent Ortiz opined (based on his purported “expertise” in interpreting such data) was evidence of a pattern of suspicious behaviour characteristic of Mr. Adams’ alleged modus operandi for unlawful firearms imports.

(There’s a long but generally undisclosed history of airlines “voluntarily” giving police access, without warrants, to PNR data, and of police using it as the basis for interrogations and searches.)

The Federal judge to which the criminal case against Mr. Adams was assigned first upheld the search warrant but then, on reconsideration, ordered all the evidence obtained from the search suppressed, on the basis of other materially false statements, made in apparent bad faith, in Agent Ortiz’s affidavit. The government, which would have no case against Mr. Adams without that evidence, has appealed that ruling to the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals.

The ruling by the District Court, the arguments to the Court of Appeals, and most of the publicity about the case have focused on questions related to firearms. But what concerns us are the issues related to ATS and its use as a surveillance and suspicion-generating system.

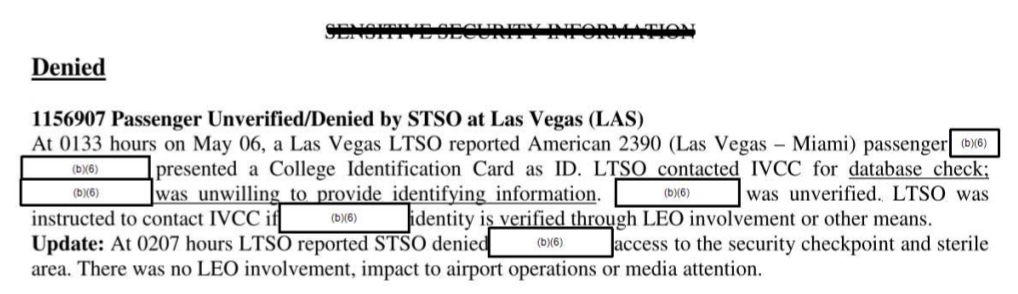

First, ATS data is neither accurate nor complete, and should not be relied on. For example, even experts may be unable to tell, from a particular PNR, whether or not it corresponds to actual travel or issuance of a ticket. (Mr. Adams says some of the DHS records of flights he allegedly took to Canada don’t correspond to flights he actually took, which is an inevitable consequence of the DHS orders to airlines to transmit copies to DHS of all reservations for such flights, including reservations that were unticketed and/or cancelled.) And license plate readers and the associated optical character recognition systems are, of course, subject to an unknown but substantial percentage of errors. (Mr. Adams says he has never traveled in some of the private vehicles in which ATS records that he crossed the US-Canada border.) Most importantly, the DHS has itself exempted ATS from the requirements of the Privacy Act for accuracy and completeness, on the basis of a claim that it is necessary to include inaccurate and incomplete data. Having done so, the government should be “estopped” from suggesting that any court or jury rely on this data.

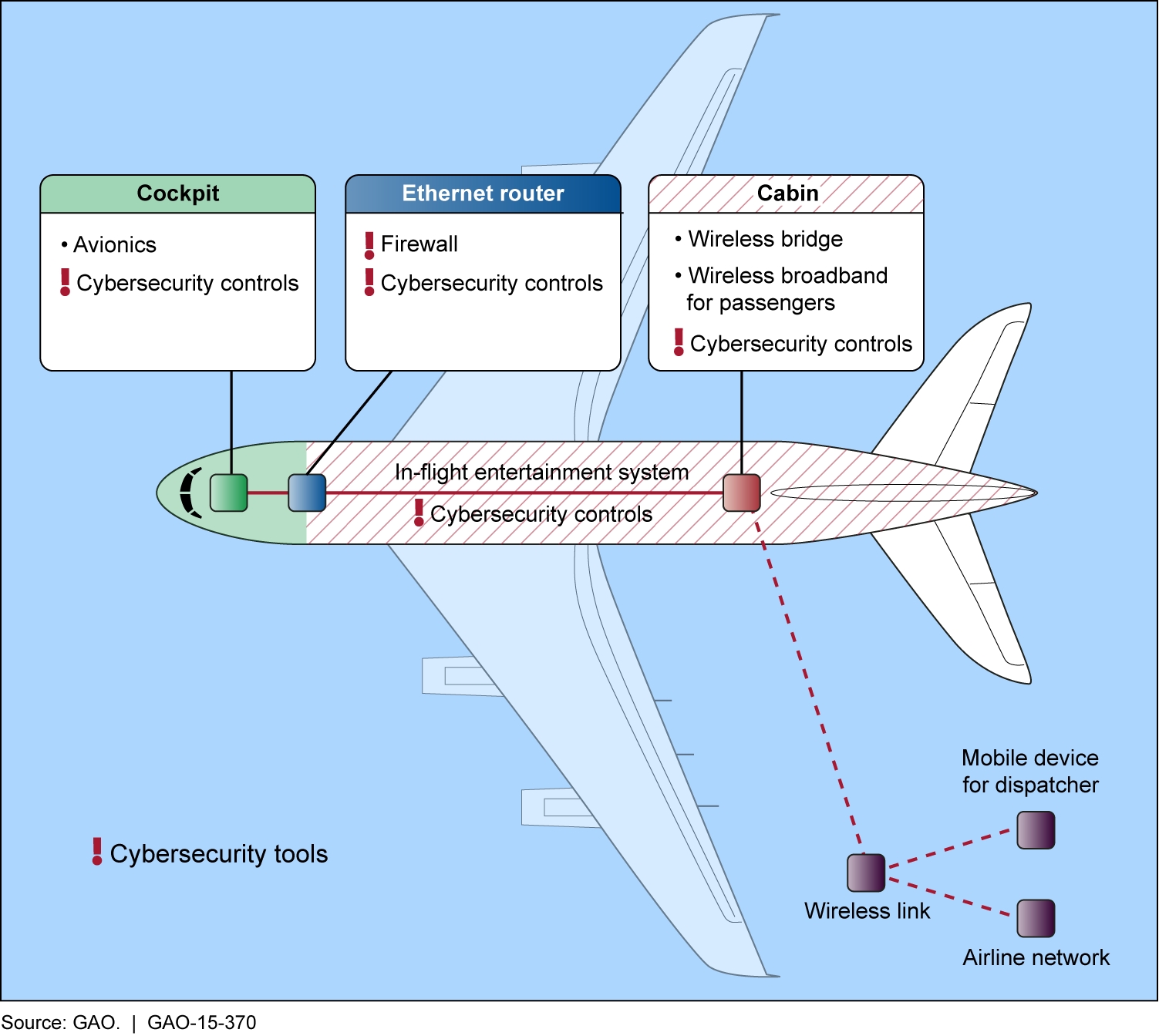

Second, if the purpose of the ATS dragnet of warantless, suspicionless travel surveillance is to develop or support suspicions of criminal activity, that is a general law-enforcement purpose that goes far beyond the scope of permissible administrative searches or seizures of personal information incident to air travel or for purposes of aviation security.

Third, the evidence presented to the court in support of the application for a search warrant, to the grand jury in support of the indictment, and to Mr. Adams as part of pre-trial discovery, appears to have included only excerpts from TECS records (entry/exit logs which are one of the components of ATS), but not the complete TECS records, and none of the Passenger Name Record (PNR) data also included in ATS. Full TECS records would include indications of the source of the data, and PNRs might well have made clear whether airline reservations had actually been ticketed and used, or had been cancelled as Mr. Adams claims.

It seems likely that the complete contents of the ATS records about Mr. Adams’ travel, including full TECS records and all PNR data, constituted potentially exculpatory evidence known to, and in the possession of, the government, which it was required to disclose to the defense pursuant to the decision of the Supreme Court in Brady v. Maryland.

More generally, it would seem that a complete ATS file for any involved individual, including complete TECS and PNR data, would constitute potentially exculpatory evidence in virtually any prosecution in which international travel might be relevant: smuggling, facilitating unlawful immigration, etc. It would be almost impossible for the government to know in which cases such data might support an alibi, support or undermine the credibility of a witness, or support or refute some other testimony or claim. If the government doesn’t proactively produce this material (as it is required to do), defense attorneys should object to this as a violation of the Brady doctrine, and/or specifically include it in routine discovery motions. (We are available to assist defense counsel in interpreting such disclosures, and/or in explaining to courts how they could be exculpatory.)

Having carried out this extensive (although unreliable) surveillance of travelers, DHS appears to be using it selectively, introducing only those excerpts, in those cases, which it thinks it can spin as suspicious — and not mentioning other portions of these files that might refute these or other government allegations. We wonder how many other criminal prosecutions this has tainted.