Kudos to Lufthansa. Coals to the DHS.

A redacted version of the report of an internal review by the DHS Office of the Inspector General (OIG) of DHS implementation of President Trump’s January 2017 “Muslim Ban” Executive Order has been made public several months after the report was prepared.

Both the manner in which the OIG report was eventually released and the contents of the report are worthy of note, as discussed below.

Federal law requires every Cabinet-level Federal department, including the DHS, to have an Inspector General. The DHS Inspector General is part of the DHS, but is appointed by the President, operates with considerable autonomy, and comes closer to the role of an “independent counsel” than does any other officer or office within the DHS.

The existence of the OIG report on DHS actions under the first “Muslim Ban” Executive Order (EO) was revealed in a November 2017 letter to Congress from IG John Roth. In this letter, IG Roth said that his office had delivered a draft of the Muslim Ban EO report to DHS “leadership” (presumably meaning the office of the Secretary of Homeland Security) in early October 2017, but that DHS leadership was taking an unusually long time to approve release of the report and had requested unusually extensive redactions. Days later, Roth took early retirement.

Open The Government (OTG) requested a copy of the report under the Freedom Of Information Act, but that request was denied on highly questionable grounds. However, two days after Open The Government and the Project on Government Oversight (POGO) appealed that FOIA denial, the DHS posted a redacted version of the report.

OTG and POGO are continuing to appeal the redactions, but even the expurgated version of the report is a damning indictment of DHS operational divisions, particularly US Customs and Border Protection (CBP), for illegal defiance of Federal court orders.

In our analysis of the Muslim Ban Executive Orders, we focused on DHS efforts to induce airlines to (illegally) deny boarding at foreign airports to blacklisted individuals and citizens of blacklisted countries, preventing refugees from reaching the US and thus preventing them from even applying for asylum.

We are struck that the OIG report assessing the legality of DHS actions focused on exactly the same issue we had highlighted: DHS efforts to induce airlines not to board citizens of the countries subject to the Muslim Ban EO on flights to the US from foreign airports, even after Federal courts in Boston and later elsewhere in the US had enjoined DHS to admit these people to the US.

The OIG concluded that, “It is our considered view that the issuance of no-board instructions violated the Louhghalam and Mohammed [U.S. District Court] orders.”

The OIG report includes examples such as the following:

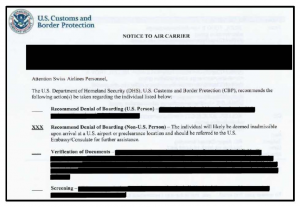

In a complaint filed in federal court on Wednesday, February 1 [2017], the traveler described her situation. On Saturday, January 28 and Tuesday, January 31, she was denied boarding for two different Boston-bound flights based on two no board instructions from CBP. During her second failed attempt, which was after the Louhghalam [U.S. District Court case in Boston] order had issued, a Swiss Air representative told her that CBP had recommended that she not be permitted to board the flight to Boston. According to the [traveler], she had a copy of the order, which she showed to the agent, but the agent advised that Swiss Air had to comply with CBP’s “no board” instruction. Separately, Swiss Air’s legal department informed the traveler’s attorney that CBP had warned the airline of “the potential for fines up to $50,000 and refusal of permission for the flight to land.” The no board instruction itself also contradicted the intent of the Louhghalam order: it stated that “[t ]he individual will likely be deemed inadmissible upon arrival at a U.S. airport or preclearance location …” as shown below:

In fact, had this traveler reached the U.S., under the Louhghalam and Darweesh [court] orders, she would have been processed for a national interest waiver and almost certainly admitted.

Around the same time… CBP was issuing “no board” instructions to prevent another 20 EO [Executive Order]-affected travelers from boarding two Lufthansa flights from Zurich to Boston…. But Lufthansa had other ideas. On Friday February 3, CBP learned that Lufthansa rejected its “no board” instructions for 20 travelers on the two Boston-bound flights. The travelers were IV [immigrant visa] and NIV [nonimmigrant visa] holders for whom NTC [CBP National Targeting Center] checks did not identify any derogatory information. CBP confirmed that its Immigration Advisory Program team lead, a Supervisory CBPO stationed in Frankfurt, personally delivered the “no board” instruction “to the Lufthansa flight manager at the departure gate” of flight 422, which was scheduled to arrive at Logan at 1:10 p.m. on Friday.

Lufthansa corporate security acknowledged the recommendation, but boarded the passengers anyway, based on guidance from Lufthansa’s legal department. Because of pending litigation, Lufthansa took the position that it would accept nationals from the seven EO-covered countries who possessed valid visas on the Boston-bound flight until February 5 (the date the Louhghalam order was set to expire). CBP was not pleased with Lufthansa’s actions. [3 lines of text redacted by the DHS.] In the end, CBP granted waivers [allowing entry to the US] for all 20 EO-affected passengers whom Lufthansa had boarded over CBP’s objections.

(There’s some ambiguity in the reference above to “Lufthansa flights from Zurich to Boston”. Lufthansa doesn’t operate flights in its own name from Zurich to Boston. This could refer to flights from Zurich to Boston by Swiss International Airlines, a subsidiary of the Lufthansa Group. But in context, it appears to refer to Zurich-originating passengers connecting in Frankfurt and/or Munich to Lufthansa flights to Boston. Lufthansa Flight 422 is a daily flight from Frankfurt to Boston. Most likley the “two Boston-bound flights” were Lufthansa’s Frankfurt-Boston and Munich-Boston flights. It’s curious that despite being a subsidiary of the same parent corporation, Swiss International apparently made a different decision from Lufthansa as to which passengers to board.)

Here what we think are the most significant takeaways from this report:

- DHS “no-board”messages to airlines are of questionable, if any, legal force. The OIG report notes that in the Muslim Ban cases, no court reviewed whether DHS has the authority to order airlines not to board certain would-be passengers or classes of passengers, because the DHS mooted lawsuits, as quickly as possible after they were filed, by rescinding no-board messages. The OIG didn’ttattempt to assess whether these messages are legally binding orders, but the language of the report is a clear indication of this uncertainty. The OIG report says that, “CBP continued to recommend that airlines ‘no board’ visa holders from the seven countries to prevent their travel to the United States,” but doesn’t explain whether or how a “recommendation” from CBP would legally “prevent” travel by common carrier.

- DHS “no-board” messages to airlines are intended to function as “no-fly” orders, and usually succeed, even if they aren’t legally binding. The OIG report generally describes CBP messages to airlines as “no-board instructions”, which implies that they are more than mere recommendations. And the OIG report cites a 2012 GAO report that, “Upon receiving a no board recommendation from CBP for a passenger, air carriers make the ultimate decision whether to deny boarding or to transport the individual to the United States. According to CBP officials, air carriers almost always follow no board recommendations becuase… the air carrier could be fined for transporting an alien to the United States who does not have a valid passport and visa, if a visa is required. (See 8 U.S.C. § 1323; 8 C.F.R. pt. 273.)” The fine in such cases is a maximum of $3,000 per passenger. It’s not clear whether the CBP threat to Swiss International Airlines of a $50,000 fine, as quoted above, was a misstatement of the law by more than an order of magnitude, a reference to some other statute, or a reference to the potential fine for some larger number of potential passengers. We were the first to publish a CBP “no board” message to an airline, after it was introduced in court in the first, and to date only, no-fly trial. Despite being worded as a “request”, that message was effective in keeping a witness — the plaintiffs’ duaghter, a US citizen — from coming to the US to testify in the trial.

- Airlines can, and sometimes do — successfully — call the DHS bluff. Lufthansa did so, and other airlines could and should have done so. We take it as a given that if the DHS believed it had the authority to issue binding “no-board” orders, it wouldn’t label its messages to airlines “requests” or “recommendations”. The US has no extraterritorial jurisdiction over who is allowed to board flights at foreign airports. As a common carrier, an airline has a legal duty to transport any would-be passenger willing to pay the fare in its published tariff. In the absence of a legally binding order, “A government agency asked us not to comply with our legal obligation to transport this person” is not a lawful excuse for refusal of transport. Nor is, “a government agency told us this person might not be admitted to a country to which they are willing to pay us to transport them”. Airline staff have neither competence nor legal authority to act as asylum judges. There is no such thing as an “asylum visa”, and it is per se impossible for a refugee to apply for asylum until they arrive in a country of possible refuge, or for anyone to determine, in advance of arrival, whether a claim of eligibility for asylum will be upheld. The proper response by an airline to a no-board “request” from CBP is, “Do you have a no-board order from a court with jurisdiction over this airline and over the airport from which this flight is to depart?”

As we’ve pointed out in our analysis of the Muslim Ban and our submissions to the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, denial of common-carrier transportation can have fatal consequences for asylum seekers and other refugees.

If, as the GAO says, “air carriers make the ultimate decision whether to deny boarding or to transport the individual to the United States,” travelers and public interest litigators need to hold airlines accountable for those decisions, and for the fulfillment of their duties as common carriers.

Travelers should insist that all airlines, every day, do as Lufthansa did on February 3, 2017. Airlines should put their legal obligations as common carriers ahead of nonbinding “requests” from US authorities to violate refugees’ or other travelers’ rights to freedom of movement.

If airlines refuse to do their job of transporting all would-be passengers to the US in accordance with their tariffs, travelers and public interest litigators should hold them accountable in the courts of the jurisdictions in which would-be passengers are denied boarding, in which those airlines are incorporated, and in the US.

Legal workers in the US and abroad concerned about preventing violations of immigrants’ and other travelers’ rights should prepare for, and advertise their availability to carry out, such litigation.

Kudos to Lufthansa for doing its job. Coals to the DHS for trying to pressure airlines to ignore their duty to the public and to violate the rights of travelers.

Pingback: Free Hilton Status and a $4.3 Million Hotel Stay - View from the Wing

Pingback: #privacy #surveillance Kudos to Lufthansa. Coals to the DHS. | Papers, Please! – Defending Sanity in the Uppity Down World

Pingback: New “National Vetting Center” will target travelers | Papers, Please!

Pingback: Will “continuous vetting” include new demands for travel information? | Papers, Please!