BART doesn’t understand the duties of a common carrier

Yesterday the Bay Area Rapid Transit district (BART) held its first public discussion of BART’s recent actions to shut off wireless telephone and data service in parts of the BART system, and to close certain BART stations on the approach of certain groups of individuals, in order to prevent the use of those communications and transportation services and facilities by certain unnamed individuals and/or organizations (to wit, people seeking to express their opposition to various BART practices) who BART thought might, at some future time, use those communications and/or transportation facilities to commit some unspecified crime(s).

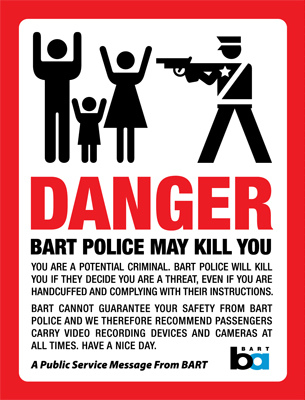

These actions by BART exemplify the post-9/11 focus of unconstitutional “pre-crime” police tactics on extra-judicial police control of access to transportation providers and other common carriers.

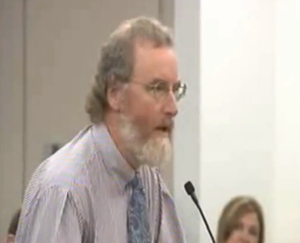

The following is a slightly extended and updated version of the testimony (video clip) given by Edward Hasbrouck of the Identity Project at yesterday’s public hearing (more) before BART’s elected Board of Directors at their Oakland, California, headquarters:

The Identity Project is part of the First Amendment Project, based here in Oakland but active nationally on civil liberties and human rights issues related to freedom of travel, movement, and assembly.

We are concerned that both BART’s selective denial of access to cellular phone and data service, and BART’s selective denial of access to transportation services, reflect a disturbing failure to understand what it means to be a “common carrier”.

As a common carrier, BART is required to provide transportation to all would-be passengers, just as a telecommunications common carrier is required to transport all would-be customers’ messages. A common carrier simply has no authority to refuse service to selected customers. That’s true regardless of what you think about who they are, where they are going, the content of their messages, the ideas or opinions they express, the reasons for which they are using your services (or those of other common carriers or third parties), or their future intentions.

If you think that certain individuals pose such a threat as to justify restricting their access to common carrier services, whether of transportation or telecommunications, you have the same recourse I or anyone else has if someone threatens to come to my house and kill me: Even in cases of the most credible, imminent, extreme, and violent threat to life and limb, I can’t just close off my block to keep them off the street. I can go before a judge, and ask the judge to issue a restraining order. That’s what hundreds of people do every day in the BART service area in, for example, domestic violence cases.

The proper place to present the arguments we’ve heard earlier in this meeting from BART’s General Manager and the Chief of the BART Police is not here before you in the BART boardroom, but in a courtroom before a judge considering a motion for an injunction.

We would likely oppose any such motion, as would many others. BART continues to allow expressive conduct, including chanting of slogans, carrying of signs, and wearing of clothing with messages, even under the most crowded and potentially dangerous conditions anywhere in the BART system: on the platforms at Coliseum station before and after sporting events. That suggests that BART’s real objection is to the content of messages that criticize BART itself, not “safety”.

Here in the BART service area in both San Francisco and Oakland, applications by police and city authorities for injunctions restricting the movements on public rights-of-way of individuals alleged to be members of criminal gangs have been extremely controversial and vigorously contested in court. But the proper forum for that deliberation is an adversary judicial proceeding, not BART’s unilateral administrative or executive fiat.

Instead of using those existing legal mechanisms to request a court order for an interruption or selective denial of common carrier services, however, BART has taken matters into its own hands as vigilantes.

As the ACLU of Northern California aptly cited in the second of two letters on this issue sent to the BART Board, long-standing California case law makes clear the parallel between transportation and telecommunications common carriers in their lack of authority to deny their service to those who they believe are likely to use it for illegal purposes: “The telephone company has no more right to refuse its facilities to persons because of a belief that such persons will use such service to transmit information that may enable recipients thereof to violate the law than a railroad company would have to refuse to carry persons on its trains because those in charge of the train believe that the purpose of the persons so transported in going to a certain point was to commit an offense.” People v. Brophy, 49 Cal. App. 2d 15, 33 (1942)

It’s unclear (it should become more clear once BART responds to a pending public records request) if the cellular telephone and data equipment that was shut down was licensed to BART or to cellphone companies.

If it was licensed to BART, those licenses and 47 U.S. Code § 214(a) (which makes express provisions, which BART didn’t follow, for applications for permission for emergency interruption of service) require BART to obtain prior approval of the FCC and/or the CPUC before it could be turned off.

If — as seems more likely in light of mentions by BART Board members of the contracts between BART and cellphone companies having been treated as “real estate” matters — the equipment was licensed to cell phone companies, and BART was merely their landlord, turning off that licensed equipment was a criminal violation of 47 U.S. Code § 333 on the part of the responsible BART staff. That’s a serious Federal offense, and violators of this law have been labeled everything from vandals and saboteurs to “domestic terrorists”.

BART had no more right to pull the plug on cellphone companies’ repeaters because BART thought some BART patrons might use them for illegal purposes than the landlord of Sutro Tower would have the right to pull the plug on San Francisco television and radio antennas on the tower if the landlord thought they were being used to broadcast hate speech or calls for illegal action.

The proper procedure would have been for BART to petition the FCC (and perhaps also the CPUC) for an emergency suspension of the licenses granted to the cellphone companies for specific equipment. The petition would have been considered and a decision made by the by the FCC. If the FCC had granted the petition, it would have ordered the cellphone companies to shut off their equipment.

BART could also have asked the cellphone companies to shut off their equipment. But it could only have asked, not ordered, and the cellphone companies would still have needed to petition the FCC and/or CPUC for permission before they could legally have complied with such a BART request.

BART should have been at most a third-party petitioner, not the decision-maker.

BART officials’ belief that interfering with licensed broadcasting equipment was necessary to prevent other crimes is irrelevant to whether they are guilty of violating 47 U.S. Code § 333. In prosecutions of environmental and antiwar activists under this statute, the defendants’ beliefs that disabling licensed telecommunications equipment including cellphone towers was necessary to prevent environmental crimes or war crimes has been deemed irrelevant and inadmissible.

BART’s Board of Directors were briefed in advance on the criminal intentions of BART’s General Manager and Chief of Police. The best way for members of the BART Board to minimize the likelihood that they will also be found culpable as accessories or co-conspirators in these crimes is for them to report to the FBI, without further delay, their knowledge that violations of 47 U.S. Code § 333 may have been committed by BART officials, and to ensure that all evidence of those crimes is preserved and made available to the FBI and the U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of California.

Selectively closing stations to deny access to certain individuals or groups might not have been criminal, although the use of police force or threat of force to implement the closure may have violated provisions of 18 U.S. Code § 245 related to programs or activities receiving Federal financial assistance. But whether or not it was a crime, it exposes BART to potentially grave civil liability for violations of 42 U.S. Code § 1983. Originally part of the Civil Rights Act of 1871, this law was enacted during Reconstruction after the Civil War specifically to prohibit interference with Federally guaranteed rights by state or local officials or under color of state or local law.

Freedom of travel and movement, including access to the services of common carriers, is such a Federally guaranteed right. Article 12 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), a treaty signed and ratified by the U.S. and thus with the force of Constitutional law, guarantees all persons lawfully within the U.S. the right of freedom of movement anywhere within the country. Freedom of movement includes both the use of public rights-of-way and the use of transportation common carriers. The U.N. Human Rights Committee, in its General Comment No. 27 (issued under its authority to interpret the ICCPR), has established specific, strict standards of necessity — including actual effectiveness and a lack of any less restrictive alternative — for administrative or legal measures that implicate this right. 42 U.S. Code § 1983 effectuates article 12 of the ICCPR by creating a Federal civil cause of action for violations of these rights by state or local officials or under color of state or local law, such as by BART or BART Police.

If you think that there’s a need for this kind of action, present those arguments to a judge with a petition for a temporary restraining order or a permanent injunction.

Other than that, get out of the business of judging BART patrons’ purposes or intentions.

Who we are, where we are going, or what we intend to do there are none of BART’s business.

And how well will that work in practice ?

Shawn Gaynor, San Francisco Bay Guardian:

BART board mulls nation’s first cell service disruption policy

http://www.sfbg.com/politics/2011/08/25/bart-board-mulls-nations-first-cell-service-disruption-policy

Other speakers from the public had similar concerns about BART overreaching its authority.

“The proper place to present the arguments we have just heard is not to this board, but in a court room before a judge considering a motion or injunction. Instead of using those existing legal mechanisms, you have taken matters into your own hands as vigilantes,” said Edward Hasbrook representing the Identity Project.

Denis Cuff, Contra Costa Times:

Hacker group posts explicit photos it says are of BART spokesman; Transit officials criticize latest Anonymous attack

http://www.contracostatimes.com/ci_18748500

Edward Hasbrook, spokesman for the Identity Project advocating free travel rights, said BART had no right to shut down cell phone service without approval of the Federal Communications Commission, the state Public Utilities Commission or a judge.

“I can’t just close my street” if a threat is feared, Hasbrook said. “I can go to a judge asking them to issue a restraining order.”

Fish Rock Road:

Special BART Board Meeting on Mobile Phone Service Interruption of August 11th

http://www.fishrockroad.org/2011/08/special-bart-board-meeting-on-mobile.html

One of the best comments came from Edward Hasbrouck of The Identity Project (PapersPlease.org). As he pointed out, the BART staff (and/or board) should not be deciding when to cut service in a case like this – they should go before a judge and get a court order. Instead they made a “vigilante” administrative decision, and that is just not kosher.

Fish Rock Road:

My email to the BART Board

http://www.fishrockroad.org/2011/08/my-email-to-bart-board.html

I have a couple of responses to statements at the meeting. I agree strongly with Edward Hasbrouck’s point that it is not appropriate for BART staff or the Board to have the sole power to temporarily shut off service; instead, the staff should get an injunction from a judge. This is in keeping with the long-standing American idea of checks and balances.

Public Knowledge blog:

Public Knowledge Urges FCC to Prevent Future BART-like Shutdowns

http://www.publicknowledge.org/blog/public-knowledge-urges-fcc-prevent-future-bar

Press release: Public Interest Groups Ask FCC to Declare BART Actions Unlawful

http://www.publicknowledge.org/public-interest-groups-ask-fcc-declare-bart-action

Emergency Petition for Declaratory Ruling Re: BART

http://www.publicknowledge.org/files/docs/publicinterestpetitionFCCBART.pdf

Pingback: Frank words during #OpBart « Waking Up Orwell

Pingback: Papers, Please! » Blog Archive » BART planning further interference with common-carrier services

Initial BART response to public records request (includes contracts with wireless carriers, but not yet any records related to cellular service interruption):

http://files.cloudprivacy.net/BART-foia-dump-Sept-6-2011.zip

Media Laws blog:

BART the tyrant

http://www.medialaws.eu/bart-the-tyrant/