Buried in the final 500-page PDF file of redacted and munged e-mail messages released by Amtrak in December 2018 in response to a FOIA request we made in 2014, we got the first hint at an answer to one of the questions that originally prompted our request:

What did Amtrak think was its legal basis for requiring passengers to show ID and provide other information, and for handing this data over to DHS components and other police agencies for general law enforcement purposes?

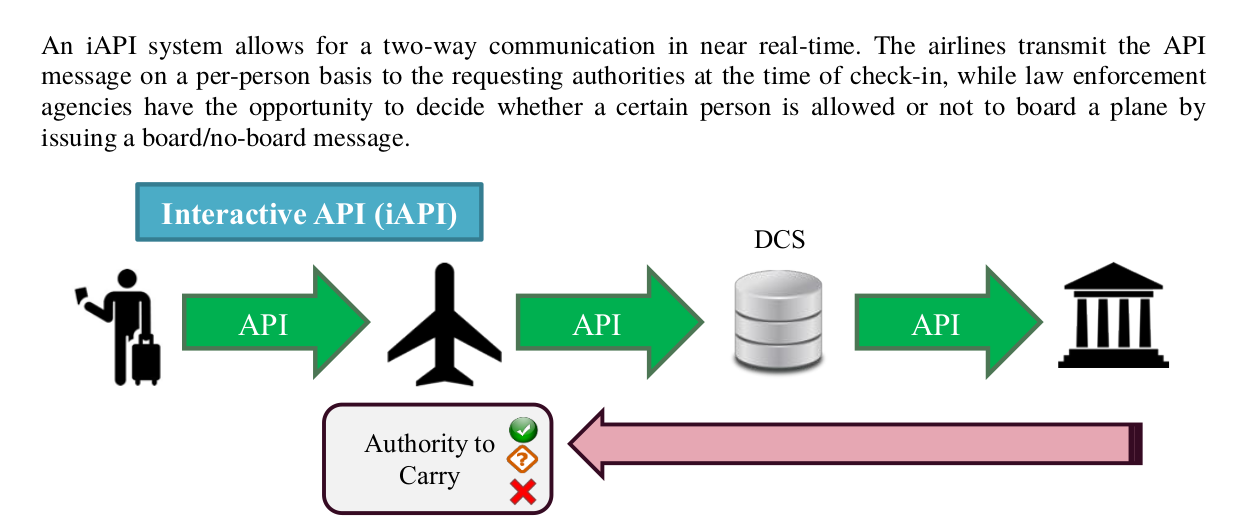

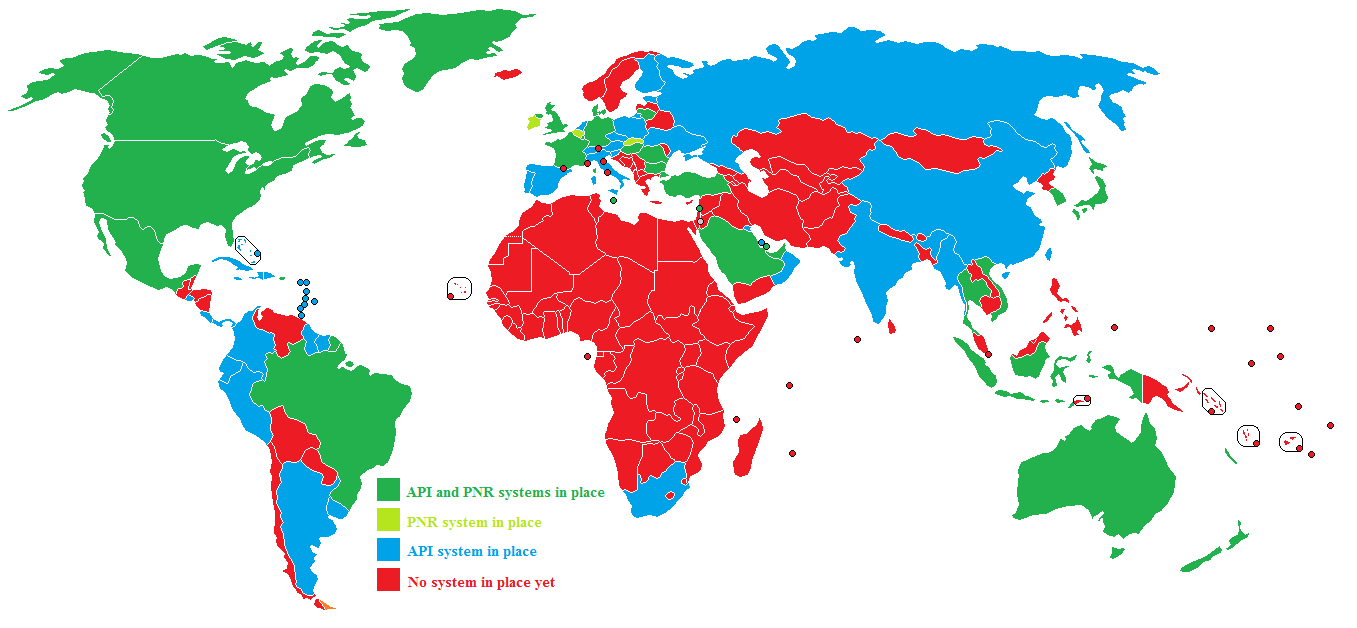

When US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) asked Amtrak to start transmitting passenger data electronically, it described this as a request for “voluntary” cooperation, noting that while the law requires airlines to collect and transmit this data to CBP, “these mandates do not currently extend to land modes of transportation” (as they still don’t today).

Despite this statement from CBP, someone at Amtrak came up with a way to describe the changes to Amtrak’s systems and procedures to require ID information in reservations for all international trains, and to transmit this data to CBP, as “required by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS)” and as “being mandated by the US Border Inspection Agencies [sic].”

In 2004, an Amtrak technology manager was asked, “Do you know if such a [Federal] mandate [to collect information about passengers] exists, or is Amtrak not obliged to participate in this program?”

The unnamed Amtrak IT manager’s response was that:

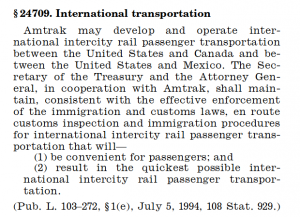

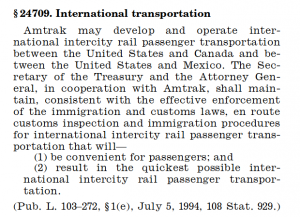

By statute, the federal government … in cooperation with Amtrak “shall maintain, consistent with the effective enforcement of immigration and customs laws, en route customs inspections and immigration procedures for international intercity rail passenger transportation that will (1) be convenient for passenger; and (2) result in the quickest possible international rail passenger transportation.” 49 USC 24709.

In other words,someone at Amtrak thinks it’s not merely permitted but required by this provision of Federal law to implement whatever level of intrusiveness of data collection and data sharing will make international trains run more quickly.

It’s arguable, to say the least, whether Congress intended this law as a mandate for ID credentials or data collection, whether collection of passenger data prior to ticketing actually expedites international trains (compared to, as used to happen, conducting customs and immigration inspections onboard while trains are in motion), or whether demands for ID and passenger information are consistent with the clause of this section requiring that measures taken be “convenient for passengers”. But someone at Amtrak seems to have interpreted this statute as such a mandate, and represented it as such to other Amtrak staff and contractors.

Are there any limits to what information or actions Amtrak would think is required of passengers on international trains, if that would keep US and Canadian border guards from stopping or delaying trains at the border for customs inspection?

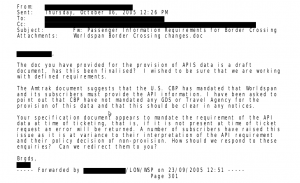

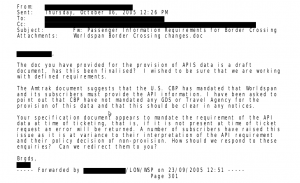

Questions about whether Advance Passenger Information (APIS) was required had been asked not only within Amtrak but by Amtrak-appointed travel agencies, as was relayed to Amtrak by a product manager for the “Worldspan by Travelport” reservation system:

There’s no indication in the documents we received as to whether this Worldspan subscriber, or any other travel agency, was given any answer to this question.

Notably, no legal basis whatsoever for requiring ID from passengers on domestic trains was mentioned anywhere in the records we’ve received from Amtrak. Nor were any records released that related to Amtrak’s privacy policy, or the legal basis for it, although such records were covered by our request. We’re still following up with Amtrak on this and other issues, and will file administrative appeals if necessary.

As part of Amtrak’s response to a separate FOIA request, however, we’ve received a redacted copy of Amtrak’s internal directive to staff regarding passenger ID requirements. According to this document, Amtrak stopped requiring passengers to show ID in order to buy tickets as of October 25, 2017. But no records related to this change, or the reasons for it, were released in response to our request.

Amtrak train crews are supposed to check ID of a randomly selected 10% or 20% of passengers. In our experience, however, Amtrak staff rarely require any passengers to show ID.

Although Amtrak is a Federal government entity, Amtrak’s of list of acceptable ID is much more inclusive than the list of ID that comply with the REAL-ID Act. Amtrak’s list of ID acceptable for train travel includes, among other acceptable credentials, any ID issued by a public or private middle school, high school, college, or university, and drivers’ licensed issued by US states and territories to otherwise undocumented residents.

Amtrak even accepts a “California state issued medical marijuana card“, which doesn’t have the cardholder’s name, only their photo. We’ll leave it as an exercise to our readers to figure out what relationship Amtrak thinks there is between being eligible for medical cannabis and being eligible for Amtrak train travel.

The most reasonable inference is that someone at Amtrak has decided that Amtrak should make a show of requiring ID, but that others at Amtrak don’t really want to turn away travelers without ID. Perhaps they recognize that travellers who don’t have or don’t want to show ID are a valuable Amtrak customer demographic.

Read More →