Do you need ID to read the REAL-ID rules?

[“The welcoming, friendly and visually pleasing appearance” of the TSA’s headquarters at 6595 Springfield Center Drive, Springfield, VA.]

[“The welcoming, friendly and visually pleasing appearance” of the TSA’s headquarters at 6595 Springfield Center Drive, Springfield, VA.]

We spent most of a day last week outside the headquarters of the Transportation Security Administration (TSA), trying and failing to find out what the rules are for the TSA’s new digital-ID scheme. What we did learn is that, by TSA policy and practice, you can’t read the REAL-ID rules, get to the TSA’s front door, or talk to any TSA staff unless you already have ID, bring it with you, and show it to the private guards outside the TSA’s gates.

The problems we have faced just trying to get access to the text of the TSA’s rules raise issuess about (recursive) incorporation by reference of third-party, nongovernmental text in regulations, secret law, and access to Federal services and rights by those without ID, as well as the underlying issues of REAL-ID, mobile driver’s licenses, and digital IDs.

In late October, as we’ve previously reported, the TSA issued a final rule establishing “standards” for smartphone-based digital IDs that would be deemed by the TSA to comply with the REAL-ID Act of 2005. These mobile driver’s licenses (mDLs) will be issued by state driver’s license agencies, but the standards incorporated into the TSA rule require that they be deployed through smartphone platforms (i.e. Google and/or Apple) and operate through government apps that collect photos of users and log usage of these credentials.

The standards themselves — the meat of the TSA’s rule — weren’t published in the Federal Register or made public either when the rule was proposed or when it was finalized. Instead, thousands of pages of documents from private third parties were incorporated by reference into the TSA’s rules, giving them the force of law, on the basis of false and fraudulent claims — the falsehood of which was easy for anyone who checked to verify — that they were “reasonably accessible” to affected individuals.

Secret laws are per se a violation of due process, and should be per se null and void. How can it be that “ignorance of the law is no excuse” if the government has kept you ignorant of the law, even when you try to find out what the law says?

You shouldn’t need ID to read the law, just as you shouldn’t need ID to travel by common carrier. But the TSA doesn’t seem to have read the Constitution.

In its final rule, the TSA repeated some of the same easily disproved lies about the availability of the material incorporated by reference in the rule that it had made in its earlier Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM). But the TSA also made a new claim that the material incorporated by reference in the rule was available for public inspection, by appointment, both at the Office of the Federal Register (a component of the National Archives and Records Administration) and at TSA Headquarters:

All approved incorporation by reference (IBR) material is available for inspection at the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) and at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). Please contact TSA at Transportation Security Administration, Attn.: OS/ESVP/REAL ID Program, TSA Mail Stop 6051, 6595 Springfield Center Dr., Springfield, VA 20598–6051, (866) 289–9673, or visit www.tsa.gov. You may also contact the REAL ID Program Office at REALID-mDLwaiver@tsa.dhs.gov or visit www.tsa.gov/REAL-ID/mDL. For information on the availability of this material at NARA, visit www.archives.gov/federal-register/cfr/ibr-locations.html or email fr.inspection@nara.gov.

We immediately contacted both NARA and the TSA at these email addresses, requesting to inspect the material incorporated by reference in this rule.

NARA told us that this material isn’t stored at the office where it will (eventually, if and when it is found) be made available by NARA for public inspection. It might take up to six weeks, possibly longer, to locate and retrieve from offsite storage:

I don’t have an estimated date for your appointment. The system we had for public access is not working and we are working to replace it. But how long that will take depends on our parent agency (the National Archives and Records Administration)….

If you wish to inspect all of the material listed in 6 CFR 37.4… it is in storage at a Federal Records Center. We will have to contact the FRC to get the material returned to us. That process generally can take up to 6 weeks; however, given the upcoming change in administration (and increased workloads for all involved), it could take longer.

If it might take months for even the Office of the Federal Register to find the text which has been incorporated in Federal regulations and has the force of law, there’s a problem. But NARA says that whether documents incorporated in regulations are reasonably available is determined by whether they are available from the agency which promulgated the regulations — in this case, the TSA — and not by whether they are available from NARA.

The TSA’s initial answer seemed more promising:

We would be delighted to coordinate a visit to TSA so you may examine the materials requested and will work to provide you with information on how to access our facilities soon.

After some back and forth by email, I arranged an appointment at the TSA’s headquarters at 9 a.m. on Monday, November 18th, for an escorted visit to inspect the documents incorporated by reference in the TSA’s “mobile driver’s license” rule. I was told that to inspect the rules I would have to provide my Social Security number and date of birth, “so that you can be cleared through Security.” I did so, reluctantly.

Despite my efforts to avoid any surprises and anticipate any problems, my visit didn’t go well.

The TSA occupies a purpose-built but privately owned new building in Springfield, VA, an hour outside Washington, DC, and a half-mile walk past the Washington Metro Transit Police Academy from the last stop on one of the Washington Metrorail lines. (There’s a virtual tour here of some parts of the interior that I never got to see.)

According to the architects, the fortifications around the building were designed to look “welcoming” and “friendly”, while actually keeping the building secure against public access:

LSG’s involvement was focused on the design of the entrance plaza and arrival sequence along the North facing public entrance of the project… LSG assisted with integration of elaborate security requirements in the site design. Security measures included K12 barriers, fences, gates, cameras and a specific vehicular circulation pattern for employees, visitors and services, etc. LSG’s focus was to integrate the security measures necessary without compromising the welcoming, friendly and visually pleasing appearance expected for TSA Headquarters.

I arrived at the guardhouse outside the gate in the TSA’s perimeter fence at 8:45 a.m., to allow time for whatever security theater might be required before my 9 a.m. appointment.

I described what happened next in an email message I sent shortly afterward:

I am outside the entrance to your building, but a guard who refuses to give his name with a badge that says “Golden Services Security” refuses either to admit me without ID, which I don’t have, or attempt to contact anyone with the TSA.

I specifically asked you, in my email message of November 1, to advise me of any access procedures for individuals without ID, who are obviously in the class of individuals impacted by the rules I want to access. You did not advise me of any ID requirement.

I request that you either admit me to access the rules, as scheduled, or provide formal notice of your decision to deny me access identifying by name and title the decision maker, the basis for the denial including any rules relied on, and any available procedures for administrative review of that decision, so that I can attempt to exercise any available administrative appeals before returning to California empty-handed, having wasted more time and money in a diligent but unsuccessful last-resort attempt to access these rules after all other access methods claimed by you proved to be unavailable.

As I noted in my first email message to you, it is impossible to reach you at the phone number specified in the final rule for access requests. You have provided me with no other phone number, and the guard refused my request that they call whatever point of

contact or escort is listed on the visitor list.I will wait outside the entrance to your building for one hour, until 10 am, unless I am ordered to leave.

I waited on an uncomfortable metal bench, exposed to the elements (luckily it wasn’t raining or snowing), just outside the fence. At 9:57 a.m., as I was about to give up and leave, someone called me from inside the building. They told me they had been assigned to escort me and were waiting for me at the “Visitor Center” inside the building. I told them, as I had said in my email message, that the guard wouldn’t let me get to the building without ID, which (as I had told them in advance) I didn’t have. They said they could only escort me once I got to the Visitor Center inside the building, and that they didn’t have “clearance” to come out to the fenceline to meet me. Catch-22.

Eventually they conferenced in — at their initiative — Mr. Anurag Maheshwary, an attorney in the Office of the Chief Counsel of the TSA. Mr. Maheshwary was listed in the Federal Register as the point of contact for legal questions about the mobile driver’s license (mDL) rule.

Mr. Maheshwary professed surprise and disbelief that I didn’t have ID, despite having been copied on my earlier queries about access procedures and protocols for people without ID. “What ID did you use to fly here from California? You must have ID.” (Wrong, even if I had flown, which I hadn’t said I had done.)

When I repeated the request I had made in my email message that, if I was to be denied access to the documents incorporated in the TSA’s rules, I be given formal notice of that denial, Mr. Maheshwary immediately demanded that the person who had called me, and had conferenced him in, disconnect him from the call. “You’ve conferenced in the wrong person!” He repeated that demand and hung up when she called back and tried again to get him to talk to me.

A little later, as I was again preparing to give up and leave, the same person called me again to say that, “We’re trying to work out how to get you access to the documents.”

As with travel by common carrier, the TSA wants to create the impression that ID is required to read the text of its regulations, and acts in practice as though ID is required, but knows that it would have a hard time defending such a policy in court. So the TSA doesn’t put this policy in writing, and backs down (or at least claims that some alternative, albeit an inconvenient one, is available for people without ID) when confronted with people without ID who it perceives as sufficiently able and willing to assert their rights.

Shortly after 11 a.m., by which time I had been sitting on the Group W bench for more than two hours, a TSA staffer came out with two large TSA-logo tote bags of documents.

One bag, which I was allowed to take with me, contained about ten pounds of copies of documents that are (purportedly) freely available online. Getting these documents directly from the TSA allowed me to be certain that they matched — or at least were claimed by the TSA to match — the text incorporated by reference into the TSA’s rules. That wouldn’t be possible with copies obtained from a private publisher or other third party, who would be neither able, willing, nor required to warrant that the copies they provided or sold matched what the TSA had depostied with the Office of the Federal Register. So that take-home bag had some official significance, but held no big surprises.

The other bag, only slightly smaller, contained copies of documents that the TSA conceded weren’t freely available, but that it wouldn’t allow me to take with me. I was alloted not more than three hours to inspect them, sitting on a bench outside with my TSA minder sitting at the other end of the bench (equally uncomfortably, I presume) to make sure I didn’t try to take away any of the non-public documents included in the TSA’s rules.

After another hour, around noon, my minder found another bench at a bus stop nearby that, while equally uncomfortable for us both, was at least partially shielded from the wind.

After yet another hour, a little after 1 p.m. — by which time I needed a toilet and was getting increasingly cold, not having dressed to spend five hours outside — my TSA minder (who had been busy texting persons unknown on his phone) told me that arrangements had been made for me to be escorted into the building to continue my reading of the bag of non-public documents. I was given no explanation as to why this hadn’t been done four hours earlier when I arrived for my scheduled appointment.

An armed guard came out, and he and the business-suited minder who had been sitting on the bench with me escorted me through the gate in the fence and across no-man’s-land to the entrance to the building. After going theough a metal detector, I was escorted to a restroom (at least they waited outside) and then back out past the metal detector to a conference room just inside the outer entry door that appeared to be there specifically for the purpose of meetings with visitors not cleared to go further into the building.

In the limited time that I was allowed to spend with these documents, I was able to confirm that they require that mDL credentials be “provisioned” through a TSA-approved app on a TSA-approved device, with that device biometrically “bound” to an individual. The process of “presenting” a digital ID will be a four-way interaction between the individual, the app (it’s unclear whether or how the user will be able to authenticate the app or know what it is doing), functions on the device to collect biometrics (controlled, in all likelihood, by an operating system with root privileges whose actions can’t be monitored or controlled by the individual), and the credential-issuing driver’s license agency.

mDL apps will be required to log each time a digital ID is presented, and to whom. This is described as a measure to protect ID-holders’ privacy, despite the obvious risk posed by police or others being able to know when and to whom you have shown your ID. If you use your digital ID for age verification to show that you are old enough ton be allowed to access adult information about sexual health or abortion, that fact will be logged on your device.

Supposely these logs will be available only to the device owner. But in reality, they will also be available to anyone who seizes the device while it is unlocked, cracks the device lock with forensic or criminal tools, or forces an individual — legally or illegally — to unlock it.

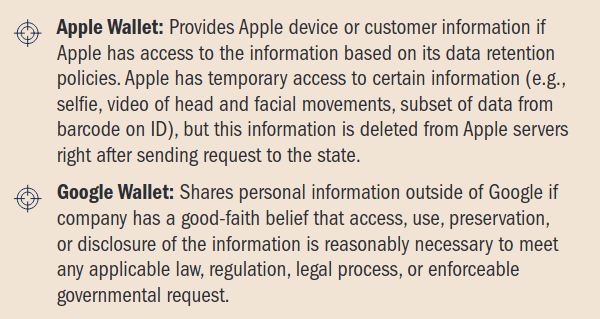

The TSA is already issuing guidance to other law enforcement agencies on the information about the usage of these digital IDs that may be available to and via Google or Apple:

[excerpt from DHS Mobile Driver’s License (mDL) Investigative Aid]

[excerpt from DHS Mobile Driver’s License (mDL) Investigative Aid]

But there’s more. To my dismay, if not surprise, I found that the non-public documents incorporated by reference in the TSA’s rules themselves incorporate by reference other documents, many of them also non-public.

How many levels of recursion do we have to follow to get to the bottom of the TSA’s rules? It’s turtles all the way down.

After leaving the area, I sent the following message to the TSA:

Yesterday we finally saw the non-public documents incorporated by reference in the mDL NPRM and Final Rule. It was immediately apparent from the volume and technical nature of this material that understanding, much less assessing or responding to, these documents would require at least several weeks and consultation with technical specialists who are not necessarily available or willing to travel to Springfield.

It is clear that neither we nor other members of the public have been provided with “reasonable” access to this material.

It also appears that your agency knew when you designated your building in Springfield as the location where these documents were purportedly accessible to the public [that it] was encircled by a guarded fence, and that members of the public without ID were not permitted even to approach the building or speak with any TSA employee. Having fenced yourself off from the public, it is fraudulent[,] and compelling evidence of bad faith[,] to claim that this inaccessible building is accessible to the public.

You cannot claim to have been taken by surprise. In our comments on the false and fraudulent claim in the NPRM that these documents were available for inspection at some unspecified DHS facility, we specifically raised the potential problem of access or entry without ID:

“Access procedures are especially critical with respect to this proposed rule because ‘the class of persons affected’ – the relevant category pursuant to 1 CFR § 51.7(3), as quoted above – obviously includes individuals who do not have ID deemed compliant with the REAL-ID Act.

“It is unclear what, if any, procedures have been established to enable individuals who do not have ID deemed compliant with the REAL-ID Act to obtain access to the relevant premises at ‘DHS Headquarters’, at whichever of the many possible locations that might be, to inspect the material proposed to be incorporated by reference into the proposed rule.

“Individuals seeking to review this material can’t simply go the specifiedaddress, since no address is specified, even if they would be allowed in the door, which they probably wouldn’t.”

We diligently sought to avoid these problems. We asked explicitly, in writing, in advance of our appointment, whether there was any protocol for access to this building by people without ID. We also asked for a point of contact and phone number we could call in case of access problems. We were provided with no point of contact or phone number, and were told of no ID requirement.

Individuals may need a license from a government agency to operate a motor vehicle. They do not need a license to read the law or to travel by common carrier. If the TSA or any other agency proposed a rule to require ID to read the law or travel by common carrier, we and many others would oppose it, for multiple reasons. But no such rules have been promulgated.

One of your staff asked me yesterday how I had traveled to the DC area, whether I had traveled by air, and whether I has shown any ID to do so. As a matter of principle and personal security, I do not wish to discuss my travel history, modes, or plans with you, and I am not required to do so. But the consistent position of your agency in litigation has been that no Federal law or regulation requires airline passengers to have, to carry, or to show ID. The responses by your agency to some of our FOIA requests confirm that, as you know, people fly without ID every day.

“The public” includes individuals who do not have ID, and to be accessible to the public, documents or services need to be accessible to those without ID.

After two hours waiting outside your gatehouse, getting increasingly cold, I was able to leaf through some of the non-public IBRs documents in the brief and inadequate time available. But the material I was allowed to look at was incomplete. Many of the non-public documents incorporated by reference in the Final Rule themselves incorporate by reference additional documents, some of them also non-public, which I was not shown. I have attached to this message, as a non-exhaustive example, the list of documents incorporated by reference in one of the ISO/IEC documents incorporated by reference in the Final Rule.

By the explicit terms of the documents IBRd in the final rule, these *additional* documents constitute part of, are essential to understanding, and are included in the requirements of the documents IBRd in the rule.

Just as the IBRd documents form part of the rule and have the force of law, all of the these documents IBRd in the documents IBRd in the rule form part of the rule and have the force of law. Compliance with these other recursively IBRd documents is required for compliance with the rule.

All such documents, at any level of recursion, are included in our right of access and our request for access to all documents IBRd in the rule….

Presumably you have them in house, since by their own explicit terms they are essential to understanding, and form part of, the documents IBRd in your rules. If you don’t have them available for me to look at today, I request that you make them accessible to the public without my having to return to the DC area.

We’ve been promised a response from the TSA by December 2nd. In the meantime, we have reported to the Office of the Federal Register that many of the documents incorporated by reference in the TSA’s mDL rule, including those recursively incorporated by reference, are not reasonably available from the TSA. The approval for incorporation by reference of these documents should be rescinded, and the rule should be withdrawn.

Pingback: 你需要身份证来阅读关于真实身份证规则的内容吗? - 偏执的码农

I read that whole thing, and I’m Australian. We are facing similar pushes of closed Digital ID here also, but it is likely that it will be even more of a black box. Thank you for giving insights into the few words available on the expected technology to be used and showing the danger of unexpected invasion of privacy of which there appears to be none if we comply with these new technologies.

Hacker News discussion of this article:

https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=42239952

@ND – The standards defining the general operational concept for these digital IDs that are incorporated into the TSA rule in the US are primarily international (ISO and ICAO), althogh supplemented by some US-specific rules from AAMVA. My guess is that Australia and other countries will mostly follow the ISO and ICAO standards, although they might layer some other rules on top.

Look at the bright side. At least it wasn’t Kamala Harris you had to deal with that day as a greeter. Talk about getting non-answers.

Pingback: Do you need ID to read the REAL-ID rules? – Cyber Geeks Global

Amazing persistence! Bravo!

I’ve run into this “include by reference” legal bullshit before in housing. The International Building Code (IBC) is copyrighted by an organization and all laws “include by reference”. Which means the law is owned by a corporation. (It’s a non-profit corporation, but one that pays its CEO exceptionally well.)

I looked for a donate button but didn’t find it. Would donations help?

P.S. I was unable to use this website fully on my iPhone. The “hamburger” menu didn’t open. (iPhone 11 Pro, iOS 17.5.1, Safari browser)

@Michael Nahas – Our apologies. The “hamburger menu” doesn’t work on some device/browser combinations. We are aware and working on it.

Thank you for your support! At present, we need public awareness (please amplify), people willing to take action (don’t show ID, even if they make it inconvenient for you), and lawyers (get in touch if you might be willing to fund litigation, or provide pro bono legal services) more than money.

Pingback: Daily Links: Wednesday, Nov 27th, 2024 | From Pixels to Particles

Thank you for your efforts. I do not expect anything better from the next administration, though I did not expect anything better from the last. You can go back thousands of years of years and bureaucrats grasping a little power have always been around. Sadly today they have better tools to use.

Pingback: Monday assorted links - Marginal REVOLUTION

Pingback: Monday assorted links | Factuel News | News that is Facts