Restriction of movement is a punishment like banishment

A Federal Court of Appeals has found that the latest version of Michigan’s “Sex Offender Registration Act” (SORA), including restrictions on where registrants can live, work, or “loiter”, constitutes a form of punishment intended to inflict pain or unpleasant consequences. “More specifically, SORA resembles, in some respects at least, the ancient punishment of banishment,” according to the 6th Circuit Court of Appeals.

Both Federal and state governments have enacted a variety of misleadingly misnamed “sex offender registration” laws.

Despite being labeled as applying to “offenders”, these laws typically apply also to ex-offenders who have completed their entire sentence of incarceration, parole, and /or probation. These ex-offenders are subject to few legal restrictions except those of the “sex offender registration” laws and the no-gun list.

And while they are described as “registration” laws, these laws almost invariably require more than mere registration. This parallels the government’s typical euphemistic use of the term “watchlists” for what are, in fact, blacklists or blocklists.

“Registration” laws typically restrict and regulate the exercise of First Amendment rights and rights recognized by international human rights law, including the rights to freedom of speech and freedom of movement, of people who are required to register. In several states, these laws restrict free speech by prohibiting use of unregistered Internet access accounts or “identifiers” (whatever that means) by ex-offenders who are subject to these laws. In a growing number of states, these laws restrict freedom of movement and residence by prohibiting registrants from living or working within a specified distance of any school — a distance which, in a populated area with neighborhood schools, can prohibit registrants from legally living anywhere in a municipality or community, or force them to live in wilderness or wasteland encampments without water, sewer, or electric service in order to stay far enough away from any school.

As we have reported, a Federal District Court judge has issued a preliminary injunction prohibiting California from enforcing its requirement for registration of Internet service accounts and identifiers, and that injunction has been upheld by the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals. The lawsuit challenging the California law drags on, however, while the court keeps giving the state more time for its legislature to try to “fix” the law to make it Constitutional.

But in contrast to this judicial rejection of some “registration” laws that restrict ex-offenders’ free speech on the Internet, courts have upheld restrictions on registrants’ residency, employment, and movement against a variety of challenges. So we were especially pleased that last week’s opinion by the 6th Circuit in Does v. Snyder recognizes that both the restrictions on movement and those on Internet speech in the Michigan SORA amount to “punishment”:

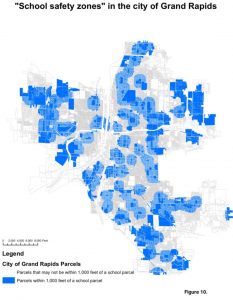

SORA resembles, in some respects at least, the ancient punishment of banishment. True, it does not prohibit the registrant from setting foot in the school zones… But its geographical restrictions are nevertheless very burdensome, especially in densely populated areas. Consider, for example, this map of Grand Rapids, Michigan, prepared by one of Plaintiff’s expert witnesses:

Sex Offenders are forced to tailor much of their lives around these school zones, and, as the record demonstrates, they often have great difficulty in finding a place where they may legally live or work. Some jobs that require traveling from jobsite to jobsite are rendered basically unavailable since work will surely take place within a school zone at some point.

The John and Mary Doe plaintiffs in the Michigan lawsuit were convicted before the SORA law was enacted. The court found that, because the law imposed imposed retroactive “punishment” on the plaintiff, it was an unconstitutional ex post facto law as applied to the plaintiffs:

We conclude that Michigan’s SORA imposes punishment. And while many (certainly not all) sex offenses involve abominable, almost unspeakable, conduct that deserves severe legal penalties, punishment may never be retroactively imposed or increased…. As the founders rightly perceived, as dangerous as it may be not to punish someone, it is far more dangerous to permit the government under guise of civil regulation to punish people without prior notice. Such lawmaking has “been, in all ages, [a] favorite and most formidable instrument[] of tyranny.” The Federalist No. 84, supra at 444 (Alexander Hamilton)…. The retroactive application of SORA’s 2006 and 2011 amendments to Plaintiffs is unconstitutional, and it must therefore cease.

The court didn’t reach the question of whether the law would be Constitutional as applied to people convicted after its enactment, but did express strong doubts about how it would rule in such a case:

As we have explained, this case involves far more than an Ex Post Facto challenge. And as the district court’s detailed opinions make evident, Plaintiffs’ arguments on these other issues are far from frivolous and involve matters of great public importance. These questions, however, will have to wait for another day because none of the contested provisions may now be applied to the plaintiffs in this lawsuit, and anything we would say on those other matters would be dicta. We therefore reverse the district court’s decision that SORA is not an Ex Post Facto law and remand for entry of judgment consistent with this opinion.