Amtrak admits passenger profiling but not DHS collaboration

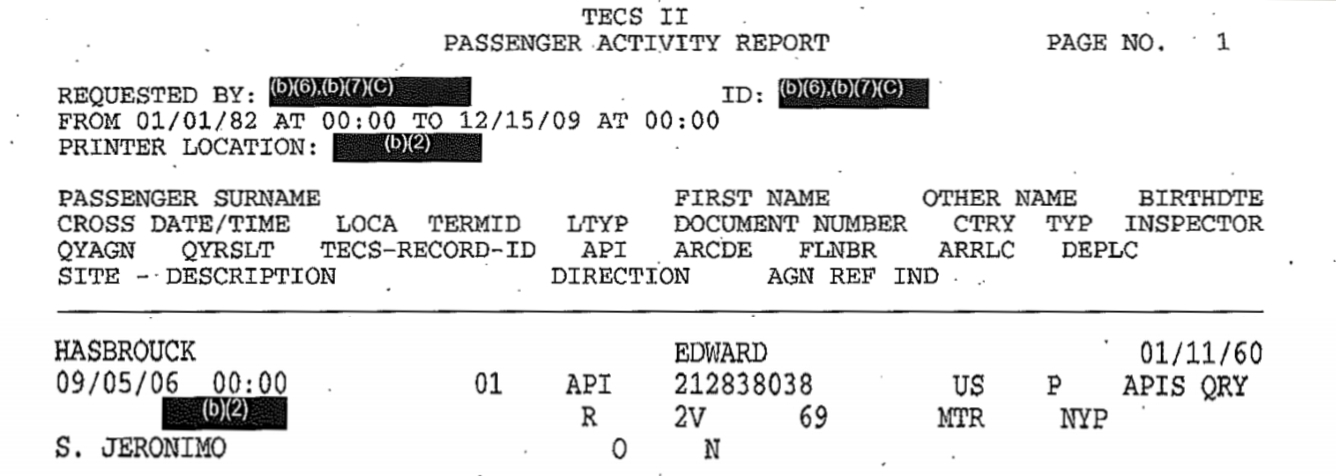

[Excerpt from DHS “TECS” travel history log showing API data extracted from the reservation for a passenger on Amtrak (carrier code 2V) train 69 from Penn Station, New York (NYP) to Montreal (MTR). “QYRSLT” redacted by DHS (at left on second line from bottom) is result of pre-crime risk score query to DHS profiling system. Click on image for larger version.]

[Excerpt from DHS “TECS” travel history log showing API data extracted from the reservation for a passenger on Amtrak (carrier code 2V) train 69 from Penn Station, New York (NYP) to Montreal (MTR). “QYRSLT” redacted by DHS (at left on second line from bottom) is result of pre-crime risk score query to DHS profiling system. Click on image for larger version.]

Amtrak has admitted to profiling its passengers, while improperly withholding any mention of its transmission of railroad passenger reservation data to DHS for use in profiling and other activities.

In response to a Freedom Of Information Act (FOIA) request from the ACLU, Amtrak has disclosed profiling criteria that Amtrak staff are instructed to use as the basis for reporting “suspicious” passengers to law enforcement agencies. As the ACLU points out in an excellent analysis in its “Blog of Rights”, pretty much everyone fits, or can be deemed to fit, this profile of conduct defined as “indicative of criminal activity”.

It’s suspicious if you are unusually nervous — or if you are unusually calm. It’s suspicious if you are positioned ahead of other passengers disembarking from a train — or if you are positioned behind them.

Normal, legal activities are defined as suspicious: paying for tickets in cash (Amtrak and Greyhound are the common carriers of last resort for the lawfully undocumented and unbanked), carrying little or no luggage (how many business day-trippers on the Acela Express are carrying lots of luggage?), purchasing tickets at the last minute (also the norm for short-haul business travelers), looking around while making telephone calls (wisely keeping an eye out for pickpockets and snatch thieves, as Amtrak police and notices in stations advise passengers to do), and so forth.

“Suspicion” based on this everyone-encompassing profile is used to justify interrogations and searches of Amtrak passengers, primarily for drugs but also for general law-enforcement fishing expeditions. Suspicion-generation is a profit center for Amtrak and its police partners: The documents obtained by the ACLU from Amtrak include agreements with state and local police for “equitable sharing of forfeited assets” seized from passengers or other individuals as a result of such searches.

The ACLU requested, “procedures, practices, agreements, and memoranda governing the sharing of passenger data with entities other than Amtrak, including but not limited to… other… federal… law enforcement agencies;” and, “Policies, procedures, practices, agreements, and memoranda regarding whether and how passenger data is shared with any law enforcement agency.”

But Amtrak’s response included no records whatsoever concerning the provision of passenger data obtained from Amtrak reservations to DHS or any other government agency.

We know that DHS obtains information from Amtrak about all passengers on all international Amtrak trains. DHS has disclosed this in public reports, and we have confirmed it from DHS responses to FOIA and Privacy Act requests. The example at the top of this article is of a DHS “TECS” travel history log showing Advance Passenger Information (API) data extracted from a record in Amtrak’s ARROW computerized reservation system for a passenger traveling on Amtrak (carrier code 2V) train number 69 in the outbound direction from the US (“O”) from Penn Station, New York (station code NYP) to Montreal (MTR). The entry in the “QYRSLT” column redacted by DHS is the result for this passenger and trip of the pre-crime risk score query to the DHS profiling system.