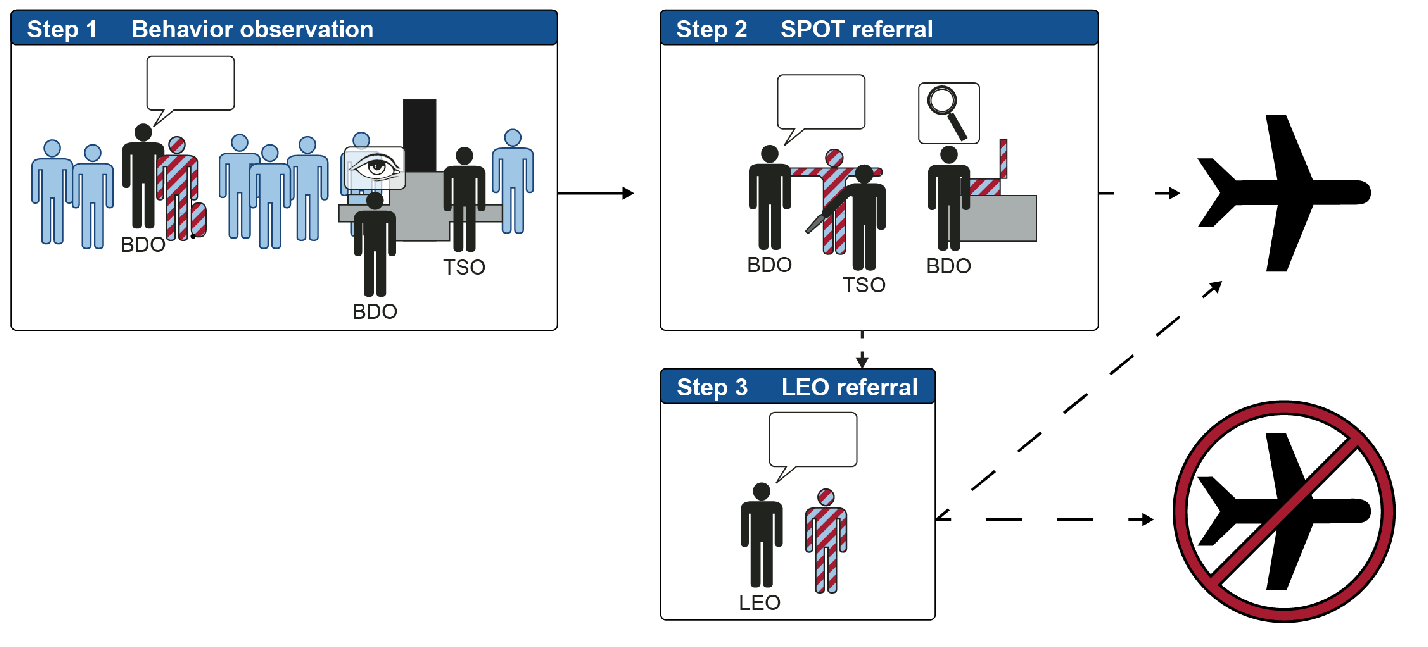

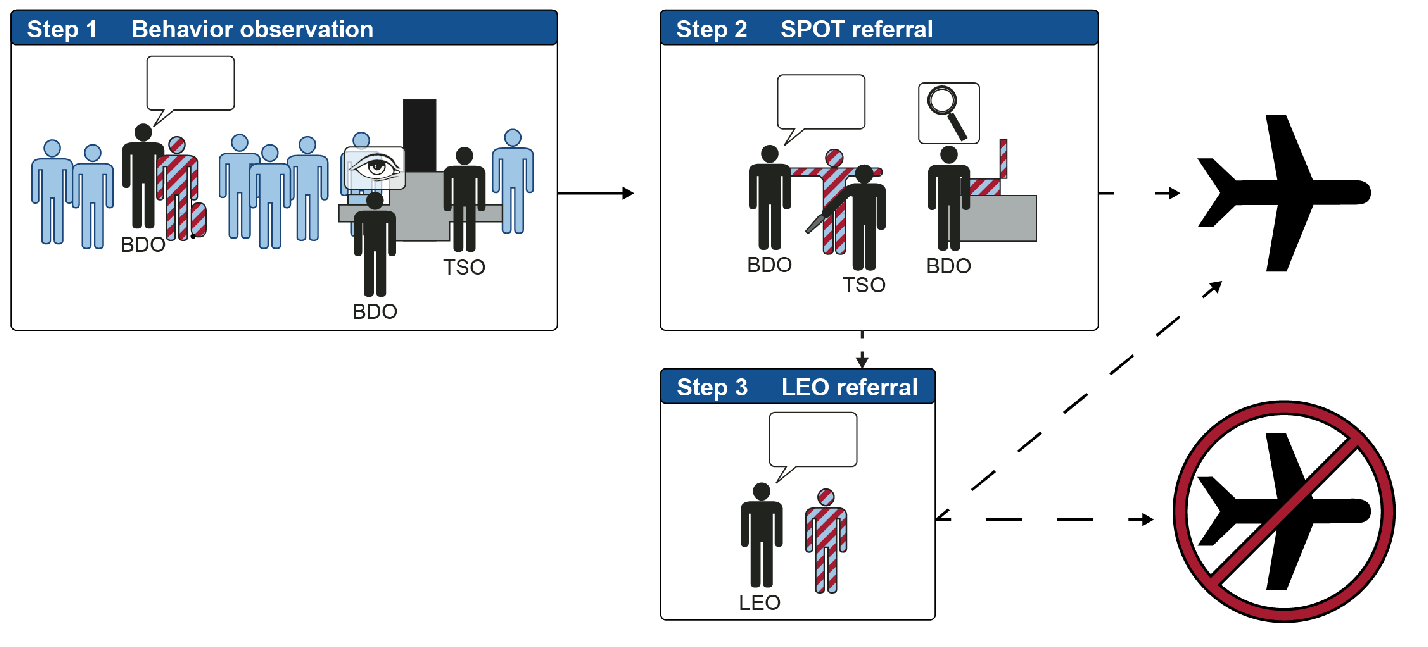

[The TSA uses appearance profiles to decide whether to search you and/or your luggage, interrogate you, call the police, or allow you to fly. (Diagram from GAO report. Click image for larger version.)”]

[The TSA uses appearance profiles to decide whether to search you and/or your luggage, interrogate you, call the police, or allow you to fly. (Diagram from GAO report. Click image for larger version.)”]

We’ve likened the TSA’s attempts to predict which travelers are would-be terrorists on the basis of their identities and profiles to the “pre-crime” police in the fictional film, Minority Report, who use “pre-cogs” with supernatural powers to predict who will commit future crimes.

We’ve also pointed out that in reality, as distinct from Hollywood fantasy, there’s no such thing as a “precog”. The Constitution presumes that we are innocent until proved guilty, and requires probable cause (as determined by a judge, not a self-proclaimed or TSA-certified psychic) to believe that we have already committed a crime before we can lawfully be arrested.

Having said that, we’re pleased to see that members of Congress and government auditors are (finally) beginning to come to their senses — as the characters in “Minority Report” eventually did — and questioning whether the TSA really has any “pre-cogs” on its payroll, or what the TSA has gotten for its $900 million outlay on “Behavior Detection Officers” and “Screening Passengers by Observation Techniques” (SPOT).

At a hearing last week before the Subcommittee on Transportation Security of the House Committee on Homeland Security, Rep. Mark Sanford asked John Pistole, the former FBI agent who is now Administrator of the TSA, whether travelers should “have to go through a screening process based on somebody’s interpretation of what might be in your brain.” Rep. Sanford pointed that a wide variety of factors — including the TSA’s own actions — might lead to stress, fear, and the “behaviors” that the TSA has defined in a (secret) point-scoring system as indicia of terrorist intentions.

In response, Pistole admitted that, “There’s no perfect science, there’s no perfect art of this.”

“Imperfect” isn’t the right word for the SPOT program. In fact, there’s no scientific basis for it at all, according to a report and testimony at the same hearing by the Government Accountability Office.

In addition to a detailed debunking of the lack of scientific evidence to support the TSA’s claims to paranormal ability, the GAO report gives more information than has previously been made public concerning what the TSA’s “behavior detection officers” (BDOs) actually do.

The TSA’s goal is mind reading. TSA “Behavior Detection Officers” (BDOs) are supposely trained to deduce mental states from external appearances and visible behaviors:

According to TSA’s strategic plan and other program guidance for the BDA [Behavior Detection and Analysis] program released in December 2012, the goal of the agency’s behavior detection activities, including the SPOT program, is to identify high-risk passengers based on behavioral indicators that indicate “mal-intent.”

But can BDOs read our minds? Presumably, the measure of their success in doing so would be how many (if any) of the travelers they flag as “mal-intentioned” are eventually found guilty of aviation-related terrorist offenses. Does that ever happen? The GAO couldn’t tell, because the TSA doesn’t keep records of that:

TSA was unable to provide documentation to support the number of referrals that were forwarded to law enforcement for further investigation for potential ties to terrorism. Further, according to FAMS [Federal Air Marshalls Service] officials, when referrals in TISS [Transportation Information Sharing System] are forwarded to other law enforcement officials for further investigation, the FAMS officials do not necessarily identify why the referral is being forwarded. That is, it would not be possible to identify referrals that were forwarded because of concerns associated with terrorism versus referrals that were forwarded because of other concerns, such as drug smuggling. [emphasis added]

Like most TSA personnel, and despite the job title of “officer”, BDOs and TSOs are not law enforcement officers. As the diagram above makes clear, they can and do impose “administrative” sanctions including more intrusive searches of travelers and our luggage, interrogation of travelers, and denial of the right to travel. The TSA also claims the right to impose administrative fines for insufficient, or insufficiently groveling, “cooperation” with their search, interrogation, or anything else it decides is part of “screening”. But beyond that, unless they want to take the risk of liability for making a citizens arrest, TSA employees and contractors depend on local law enforcement officers (LEOs) to provide their muscle.

What happens when the TSA refers travelers picked out by its BDO “pre-cogs” to local police?

99.4 percent of the passengers that were selected for referral screening — that is further questioning and inspection by a BDO — were not arrested. The percentage of passengers referred to LEOs that were arrested was about 4 percent; the other 96 percent of passengers referred to LEOs were not arrested. The SPOT database identifies 6 reasons for arrest, including (1) fraudulent documents, (2) illegal alien, (3) other, (4) outstanding warrants, (5) suspected drugs, and (6) undeclared currency…. According to the validation study, the majority of the arrested passengers were arrested because of possession of a controlled substance. [emphasis added]

“Terrorist” offenses aren’t even a sufficiently large proportion of TSA checkpoint arrests to warrant their own category in the database. If there were any at all, they are merely a subset of the “miscellaneous” category.

Rather than predicting terrorist intent, the TSA is using the “behavior detection” program as a pretext for warrantless searches for general law enforcement purposes, primarily for enforcement of drug laws. That’s exactly the sort of pretextual use of a special-purpose administrative checkpoint detention and search as a general-purpose law enforcement dragnet which, as numerous courts have recognized, is prohibited by the Fourth Amendment.

Any actual interdiction of would-be terrorists is so infrequent and insignificant (or of so little relevance to the true purposes and criteria for success of the program) as not to be worth bothering to track.

Both the GAO (Congressional auditors) and the DHS’s own Office of Inspector General (OIG), in separate audits and investigations, found evidence that these warrentless searches and other sanctions were being imposed on the basis of “appearance profiles”, including profiles of ethnic and racial appearance:

With regard to information provided related to profiling, DHS stated that DHS’s OIG completed an investigation at the request of TSA into allegations that surfaced at Boston Logan Airport [“These accusations included written complaints from BDOs who claimed other BDOs were selecting passengers for referral screening based on their ethnic or racial appearance.”] and concluded that these allegations could not be substantiated. However, while the OIG’s July 2013 report of investigation on behavior detection officers in Boston concluded that “there was no indication that BDOs racially profiled passengers in order to meet production quotas,” the OIG’s report also stated that there was evidence of “appearance profiling.”

In other words, the DHS’s own investigators found that the TSA was basing its decisions (searches, interrogations, no-fly orders, referrals to police, etc.) on the basis of racial and ethnic appearance profiles — it just wasn’t using racial and ethnic profiling to meet specific quotas. All profiling by BDOs is, of course, “appearance profiling”, since all that BDOs are able to observe is external appearance. Is the absence of explicit racial or ethnic quotas supposed to make such profiling OK?

GAO auditors also received first-hand complaints of profiling from BDOs at every airport they visited:

During our visits to four airports, we asked a random sample of 25 BDOs at the airports to what extent they had seen BDOs in their airport referring passengers based on race, national origin, or appearance rather than behaviors…. Of the 25 randomly selected BDOs we interviewed, 20 said they had not witnessed profiling, and 5 BDOs (including at least 1 from each of the four airports we visited) said that profiling was occurring at their airports, according to their personal observations. Also, 7 additional BDOs contacted us over the course of our review to express concern about the profiling of passengers that they had witnessed.

If there is any small silver lining in the GAO’s latest report, it’s that despite complete disregard for the Fourth Amendment, the TSA has at least begun to pay lip service to the Fifth Amendment rights of travelers to remain silent when questioned by TSA employees or contractors:

In August 2012, the Secretary of Homeland Security issued a memorandum directing TSA to take a number of actions… These actions include a revision of the SPOT standard operating procedures to, among other things, clarify that passengers who are unwilling or uncomfortable with participating in an interactive discussion and responding to questions will not be pressured by BDOs to do so. [emphasis added]